| Julio

Antonio Leslie Judd Ahlander Art Critic Year after year Julio Antonio’s work continues to grow and assert its authority. Arriving in Miami in  1986,

he had a difficult time at first making a place for himself among the

established artists who had come here in the sixties and later in the

Mariel Boatlift. To be free to express himself, after so many years of

“wearing a mask”, required a difficult adjustment. 1986,

he had a difficult time at first making a place for himself among the

established artists who had come here in the sixties and later in the

Mariel Boatlift. To be free to express himself, after so many years of

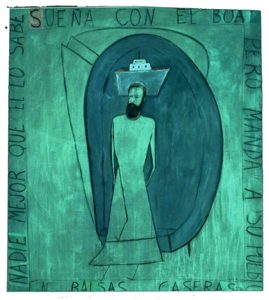

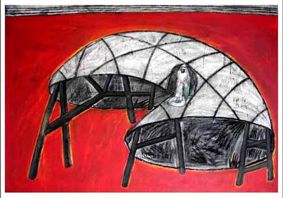

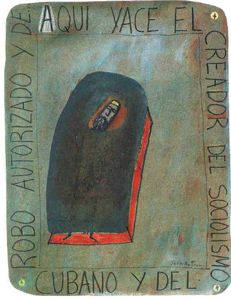

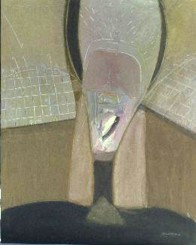

“wearing a mask”, required a difficult adjustment.At the time of his arrival, Julio Antonio was already a seasoned artist, having attended both the San Alejandro Art School and the Higher Institute of the Arts. It was therefore not a question of learning to pain but of finding the images which would best reflect his personal anguish and anger at the regime he had left behind. Early work had embraced thickly painted kite-like masked figures, recalling the masks of Santeria, the Afro-Cuban religion. They spoke cogently of the need to disguise and dissemble that which was the role of the Cuban artist. Gradually the work led to a spiral form circling into a tightly controlled center. Dragged along this circular path were figures and animals who struggled helplessly to avoid the centrifugal force of the tightening coils. In the center were images of the dictator, of prisons and bunkers, of torture and death. The artist has said that at that time there were only three possibilities for the Cubans: jail, escape or suicide. Growing out of the spirals are the new works, which are thinly painted and subdued in color. They  are a departure from the

brilliant, often garish tones and thick impasto of the spirals. Now

they have assumed the shape of a pinwheel, with an even stronger sense

of circular motion which the artist says is like the Cuban economy,

blowing in the winds. In the center of the spiral a structure or

structures contain, among other images, a figure of Castro, a black

hand (denoting hidden powers), and a map of Cuba. Circling around the

center are stylized, repetitive figures which signify the blind and

irrational conformity of the fanatical followers of Castroism. are a departure from the

brilliant, often garish tones and thick impasto of the spirals. Now

they have assumed the shape of a pinwheel, with an even stronger sense

of circular motion which the artist says is like the Cuban economy,

blowing in the winds. In the center of the spiral a structure or

structures contain, among other images, a figure of Castro, a black

hand (denoting hidden powers), and a map of Cuba. Circling around the

center are stylized, repetitive figures which signify the blind and

irrational conformity of the fanatical followers of Castroism.  Complex,

intertwining roads circle into the center, as sinuous and torturous as

the snames used in the rites of Santerial. Trapped in their vortex, man

and beast are inexorably dragged toward the central structures which

resemble concentration camps ( we are reminded that victims of AIDS in

Cuba are segregated and interned in camps as a brutally effective way

of containing the infection). Counterposed to the ropelike curves of

the roads are the stick figures of Castro’s followers: angular bodies

with double tongues and forked tails, recalling pre-Columbian

prototypes. Complex,

intertwining roads circle into the center, as sinuous and torturous as

the snames used in the rites of Santerial. Trapped in their vortex, man

and beast are inexorably dragged toward the central structures which

resemble concentration camps ( we are reminded that victims of AIDS in

Cuba are segregated and interned in camps as a brutally effective way

of containing the infection). Counterposed to the ropelike curves of

the roads are the stick figures of Castro’s followers: angular bodies

with double tongues and forked tails, recalling pre-Columbian

prototypes.But even without deciphering the meaning of the ideograms, the impact of the work itself is extraordinary in its intensity and control. The screaming mouths spouting speeches that seemed an indelible part of the artist’s nightmares have given way to forms more abstractly used, as though the painter has finally escaped the mind-numbing cacophony that haunted him. He seems now to be coming to terms with his past, and the new works are well integrated, rising over over-emotional polemic in a successful effort to create universal symbols which are at the service of a broader vision. La magia personal de Julio Antonio Carlos M. Luis Especial/El Nuevo Herald La lectura que sugiere Julio Antonio (Cuba, 1955) de su pintura, posee diversos significados. En la contratapa de su libro Relaciones estructurales, que recoge una amplia selección de su obra, el pintor menciona varias influencias, situándolas en plena lucha de contrarios. Lo consciente y el subconsciente, lo satírico y lo trágico, lo poético y lo dramático, se contraponen en su proceso creativo, hasta crear la síntesis de su magia personal. Julio Antonio pues nos da la clave para descifrar el lenguaje de sus cuadros, cuya miniretrospectiva puede ser apreciada en la Galería Olga y  Carlos Saladrigas del Colegio de Belén. El

título de la exhibición, sin embargo, alude a otro

contenido que necesariamente posee un carácter político y

por ende circunstancial: The Art of

Being in Exile. No me voy a referir tanto a ese contenido, como

al que encierra la magia de sus mitos. Me parece -- y así se lo

comuniqué a Julio Antonio -- que lo que percibimos en sus

cuadros, trasciende cualquier referencia anecdótica a sus

experiencias personales, brindándole a su pintura un valor

universal. Carlos Saladrigas del Colegio de Belén. El

título de la exhibición, sin embargo, alude a otro

contenido que necesariamente posee un carácter político y

por ende circunstancial: The Art of

Being in Exile. No me voy a referir tanto a ese contenido, como

al que encierra la magia de sus mitos. Me parece -- y así se lo

comuniqué a Julio Antonio -- que lo que percibimos en sus

cuadros, trasciende cualquier referencia anecdótica a sus

experiencias personales, brindándole a su pintura un valor

universal.La exposición que muestra una buena selección de cuadros de mediano y gran formato, representa cabalmente la complejidad de los significados que Julio Antonio desea trasmitir. Uno de estos, en apariencia de contenido más directo, titulado La cuerda floja (1998), se nutre de diversas fuentes culturales. El esquematismo de la figura y los dos inmensos brazos que surgen de los costados de su cuerpo, se encuentran relacionados con imágenes pintadas en piedras y cavernas por los pueblos primitivos. En las figuras Dogones y Senufos se reproducen esas desmesuras. Muchos fetiches del vodoo haitiano también poseen extremidades desproporcionadas. En dibujos de Egon Schiele hallamos de nuevo, el mismo tratamiento. Es decir, que Julio Antonio prosigue por esa continua línea de artistas que han bebido de las fuentes primitivas o del arte bruto. El cuadro pues posee un doble sentido: mágico y autobiográfico. Con respecto a lo primero, Julio Antonio nos lleva a su dominio personal, dominio donde su imaginación juega libremente. La magia aplicada a las artes, fuerza necesariamente a la selección de una iconografía que la sepa expresar. Los cubistas escogieron las máscaras africanas, aunque estaban más interesados en su aspecto estructural. Los surrealistas por su parte, ampliaron su horizonte hasta llegar a la Oceanía y a la América. Julio Antonio recorre esos caminos con un espíritu lúdico, para ir descubriendo formas que se apliquen a su manera de ver la realidad. Es entonces que de su paleta surgen máscaras, totems e ídolos obedientes a lo que Fernando Ortiz definió como ''transculturación'' de imágenes. En ese proceso los símbolos y vestiduras de los ritos afrocubanos, aparecen en escenarios al lado de otras figuras pertenecientes a diversos cultos religiosos. Julio Antonio, sin embargo no se detiene ahí, yendo mucho más lejos en la confección de su  mundo.

En composiciones enmarañadas, sus personajes se encuentran

atrapados como en búsqueda de una salida que se produzca por

''arte de magia''. Aparecen entonces dos símbolos

arquetípicos en su obra: El laberinto y la espiral. Los

símbolos del laberinto y la espiral son polisémicos. Las

espirales designaron para los egipcios formas cósmicas en

movimiento. Fernando Ortiz en su libro sobre El Huracán, lo considera como

una fuerza primordial que desata funciones creadoras. El laberinto como

el famoso de Minos, es una construcción arquitectural que puede

esconder monstruos. Mircea Eliade pensaba que su función era

defender el centro o el acceso iniciático a la sacralidad. mundo.

En composiciones enmarañadas, sus personajes se encuentran

atrapados como en búsqueda de una salida que se produzca por

''arte de magia''. Aparecen entonces dos símbolos

arquetípicos en su obra: El laberinto y la espiral. Los

símbolos del laberinto y la espiral son polisémicos. Las

espirales designaron para los egipcios formas cósmicas en

movimiento. Fernando Ortiz en su libro sobre El Huracán, lo considera como

una fuerza primordial que desata funciones creadoras. El laberinto como

el famoso de Minos, es una construcción arquitectural que puede

esconder monstruos. Mircea Eliade pensaba que su función era

defender el centro o el acceso iniciático a la sacralidad.Los rituales que se producen entonces en el interior de los cuadros de Julio Antonio, hacen que vibren con esa energía ancestral. La vitalidad estallante del color, combinado con la miríada de personajes y fauna que lo pueblan, producen un poderoso efecto visual. Ese efecto proviene de lo que él justamente califica de ''neoexpresionismo''. El carácter expresionista de su pintura, se encuentra más cercano al tratamiento que un Franz Marc, Erich Heckel o Ernest Ludwig Kirchner hicieran en las suyas. La interpretación grotesca que hace Julio Antonio de la figura humana, y los desmembramientos a la que están sometidas, no obedecen sin embargo, a los mismos fines que inspiraban a los pintores alemanes. Si bien es cierto que en éstos también se encontraba la sátira conjuntamente con la tragedia, me parece que el sentido del humor ''cubano'' de Julio Antonio, le ofrece otro sentido. La tendencia cubana al ''choteo'' diluye el costado ''serio'' de la sátira (que los expresionistas poseen), poniendo al desnudo su carácter disociador. El humor pues entra a ser parte integrante de su pintura, un humor cargado de alusiones personales donde sus experiencias cubanas aparecen reflejadas. Hay mucho que añadir aún a esta importante exhibición de la obra de Julio Antonio. Las diversas corrientes que la nutren, y la amalgama de símbolos que la expresan, requieren más espacio para interpretarla debidamente. Quede pues esta reseña como un intento de señalar la importancia de la misma.• Julio Antonio: The Art of Being in Exile, Ignatian Center for The Arts, Belen Jesuit Preparatory School, hasta el 5 de abril. 500 SW 127 Ave. Un catálogo con introducción del curador Ricardo Pau-LLlosa se encuentra disponible. (786) 621-4624. El Nuevo Herald, 8 de marzo de 2009 The Synecdocic Imagination of Julio Antonio Ricard Pau-Llosa Julio Antonio is a pivotal figure in Cuban art. Born in Havana in 1950, he fled communist Cuba in 1985, first for Spain but then settling in Miami. He straddles two generations of Cuban Modernists – the Fourth (born in the 40’s) and the Fifth (born in the 50’s). Sufficiently endowed with memories of Cuba before the communist takeover in 1959, Julio Antonio endured the repression of his native land throughout the period in which he grew to manhood. This period offered a spectacle of power, resistance, and transcendence which fuels much of his work and has made him the consummated  painter of Cuba’s epic of descent into ruin and

cultural survival in exile. painter of Cuba’s epic of descent into ruin and

cultural survival in exile.Not just historically, but also stylistically, Julio Antonio is a pivotal figure. Figurative expressionism never faded in Latin America – José Luis Cuevas in Mexico, Antonia Eiriz in Cuba, Nueva Figuración in Argentina, Alejandro Obregón in Colombia, Julio Rosado del Valle in Puerto Rico, to name only a few Latin American masters who worked in this style long after it passed from the scene in Europe and North America. Julio Antonio emerged as a mature artist in this style in the 80’s as a time in which Neo-Expressionism retook the limelight in the international art scene. Precisely because figurative expressionism was an on-going and evolving style in Latin America, the paintings of Julio Antonio confidently took on a wide range of political, historical, and existential themes not seen in the European and North American revivalists of this style. In the 90’s and since, Julio Antonio has continued to explore the epic struggle between individual conscience and the machinery of power in new visual languages, centered more on a poetics of line and light than on the force of painterly gesture. An artist who masters simultaneously the epic and the aesthetic challenges of painting, Julio  Antonio is a central figure in the development

of Cuban art as well as one who has brought a unique depth to the

emergence of a distinctive, cosmopolitan art in South Florida. He is a

forger of images which incorporate dense conflicts and histories

without succumbing to the simplistically narrative. He trains symbolism

derived from European and Afro-Cuban religions on questions which

define the human condition in universal terms. Tackling the most

serious of themes, Julio Antonio is also a satirist and humorist of

great originality. However, his centrality in the art of Cuba and his

uniqueness in the art of Latin America are centered on his particular

approach to the role of tropes in visual thinking. Antonio is a central figure in the development

of Cuban art as well as one who has brought a unique depth to the

emergence of a distinctive, cosmopolitan art in South Florida. He is a

forger of images which incorporate dense conflicts and histories

without succumbing to the simplistically narrative. He trains symbolism

derived from European and Afro-Cuban religions on questions which

define the human condition in universal terms. Tackling the most

serious of themes, Julio Antonio is also a satirist and humorist of

great originality. However, his centrality in the art of Cuba and his

uniqueness in the art of Latin America are centered on his particular

approach to the role of tropes in visual thinking.Tropes which are usually studied in language and literature – and all to sparingly in art – are figures, constructs which defy the rules of literal or univocal representation. Commonly used without a second thought in everyday language, tropes are the hallmark of poetic or literary discourse. A trope  never means what it says, but it always gets

its point across. Among the most common are metaphor – which

establishes resemblance between two things – and metonymy – which

transfers values between things which are perceived together. Metonymy

rules our sense of how things belong in specific settings, while

metaphor is the source of almost all new words. However, the trope most

often overlooked in the study of how works of art live in the mind of

their makers are public alike is synecdoche. Overshadowed by the

dazzling resemblances disclosed by metaphor, and by the irrepressible

associations through proximity highlighted by metonymy, synecdoche is

often deemed, unjustly, a less potent device. Tropes play a central

role in thinking. They transform experience, language, and memory so as

to ascertain truths not available to literal discourse. never means what it says, but it always gets

its point across. Among the most common are metaphor – which

establishes resemblance between two things – and metonymy – which

transfers values between things which are perceived together. Metonymy

rules our sense of how things belong in specific settings, while

metaphor is the source of almost all new words. However, the trope most

often overlooked in the study of how works of art live in the mind of

their makers are public alike is synecdoche. Overshadowed by the

dazzling resemblances disclosed by metaphor, and by the irrepressible

associations through proximity highlighted by metonymy, synecdoche is

often deemed, unjustly, a less potent device. Tropes play a central

role in thinking. They transform experience, language, and memory so as

to ascertain truths not available to literal discourse.Synecdoche, the substitution of a whole by one of its parts (e.g. all hands on deck), operates in many of the cognitive processes by which we grasp art, drama, and literature. Synecdoche establishes continuity – co-presence with Being – between that which is a part and the whole to which the part belongs and in which it functions in a specific capacity. More importantly, synecdoche  underscores

the fact that what is grasped in its entirety as a thing – what is

immanent, immediate, objective, quantifiable, and tenable – is usually

a part of a greater whole, but because this part is being grasped

discreetly, as a whole, it also embodies and can stand in for the whole

of which it is a part. Synecdoche establishes continuity between object

and context, then, between immediacy and horizon, and that is an

essential function in the pursuit of meaning in all things, in history,

identity, life itself. underscores

the fact that what is grasped in its entirety as a thing – what is

immanent, immediate, objective, quantifiable, and tenable – is usually

a part of a greater whole, but because this part is being grasped

discreetly, as a whole, it also embodies and can stand in for the whole

of which it is a part. Synecdoche establishes continuity between object

and context, then, between immediacy and horizon, and that is an

essential function in the pursuit of meaning in all things, in history,

identity, life itself.In art and literature, synecdoche is the trope of microcosm, the figure which makes of portions the emblems of entire systems, complex unities, and assumed horizons. Evidentiary by nature, synecdoche is essential in the crafting of symbolism and theater. Who would bear the burdens of acted fiction were it not embraced as the magnifier of life itself? The power of theater, as Hamlet so deftly instructs the players before the performance of the Mousetrap, lies in the ability of a small cluster of words and actions to mirror depths that belong to life and the unspoken, intuited lessons we derive from it. Yorik’s skull can represent all of mortal humanity because of synecdoche. Even in inductive reasoning, synecdoche haunts the power of particulars to generate a transcendent conclusion. In mysteries, synecdoche enables the clue to reveal and unravel. No small matter, then, for a small thing to speak in behalf of the boundless and the profound. Julio Antonio is the rarest of Cuban visual thinkers precisely because he uses synecdoche, either to the exclusion of other tropes or as the device that rules the grasping of other tropes in an image. Metaphor governs the paintings of Wilfredo Lam, Agustín Cárdenas, Rolando López Dirube, Hugo Consuegra. There is a powerful strain where synecdoche emerges forcefully – the paintings of Carlos  Enríquez and Carlos Alfonso, the theatrical

environmental sculptures of María Brito – but a combination of

metaphor and metonymy usually dominates their images. Of course, every

tropological path can render brilliant results, and there is nothing to

indicate a hierarchy among tropes. Synecdoche, however, is more often

the purview of dramatists and poets, or even musicians (when certain

phrases and melodic motifs unify a composition), than of painters. Enríquez and Carlos Alfonso, the theatrical

environmental sculptures of María Brito – but a combination of

metaphor and metonymy usually dominates their images. Of course, every

tropological path can render brilliant results, and there is nothing to

indicate a hierarchy among tropes. Synecdoche, however, is more often

the purview of dramatists and poets, or even musicians (when certain

phrases and melodic motifs unify a composition), than of painters.In visual works of art, synecdoche emerges when there is a dynamically balanced tension between narrative and symbolic components. When the narrative component is foregrounded because the image is telling the story – as in the works of José Bedia – the symbol must assume the function of a character. That means its semantic charge is greater, for it is the character which sustains the plot. And to carry such a charge and do so in a clear manner, other tropes must come into play – hyperbole, irony, litotes, metaphor, metonymy – in the conception and execution of the painting. Conversely, when the symbolic component is stronger than the narrative – as in the paintings of Cundo Bermúdez – the tale is subsumed in setting and becomes a semantic function of the scene. Symbols in such works aspire to the immediacy of pure images, but the setting reminds us that they are freighted with references they cannot shed and plots which have unfolded and operate now as context, not action. The recurring link between the mouth and the spiral is a good example of Julio Antonio’s masterful  use

of synecdoche. In works from the late 80’s and 90’s in particular,

fang-like teeth rim the canvas, point inwardly. The teeth also line the

corridors of the spiral leading to a point of infinite disappearance.

Along the centripetal highway we see diverse figures, automobiles,

beings that recall hieroglyphs, creatures that look like masked molars

running on the inescapable paths, skeletons. The spiral is the

archetype of infinite non-repeating movement, a circle unraveling into

endless episodic circularity. The mouth is also a sense organ, and in

countless beasts a weapon. The piral could be seen, in the simplest

terms, as the representation of speech or screaming. Indeed, in some of

Julio Antonio’s paintings, spirals emerge from mouths, and on the

spiral’s bands are written what the character is saying. But in these

other spirals which pour into the core of an unnamed, universal self,

such easy metaphorics are of no use. use

of synecdoche. In works from the late 80’s and 90’s in particular,

fang-like teeth rim the canvas, point inwardly. The teeth also line the

corridors of the spiral leading to a point of infinite disappearance.

Along the centripetal highway we see diverse figures, automobiles,

beings that recall hieroglyphs, creatures that look like masked molars

running on the inescapable paths, skeletons. The spiral is the

archetype of infinite non-repeating movement, a circle unraveling into

endless episodic circularity. The mouth is also a sense organ, and in

countless beasts a weapon. The piral could be seen, in the simplest

terms, as the representation of speech or screaming. Indeed, in some of

Julio Antonio’s paintings, spirals emerge from mouths, and on the

spiral’s bands are written what the character is saying. But in these

other spirals which pour into the core of an unnamed, universal self,

such easy metaphorics are of no use.It is precisely the tooth which makes the synecdochic link work. The tooth tears, separates a piece from the whole to which it was attached, and chews it so it can become a part of the new whole – the digester. This process sustains our lives and must be repeated countless times throughout our existence. The higher functions of the mouth – speech, pleasure, aggression, et al – are also infinite, but they are centrifugal, oriented toward the world, other beings, listeners. The teeth play a role in these, but symbolically they also function as the shields of the articulating mouth, or the prison bars  of expression. It is impossible to overlook the

omnipresent exploration of the horrors of totalitarianism evident in

Julio Antonio’s work from its beginnings. It is also important to

understand that denouncing tyranny, particularly communism in his

native Cuba, serves as a historical context for works of art which live

complex lives in our minds. The mouth-spiral as stage generates an

exchange between the wave-like serrated blades and the molar-figures,

grotesque, vomiting, screaming, distatiorial – caricatures of the

tyrante in olive-green fatigues as well as of his mindless

collaborators that fill the hurricane-decibel plazas. Whether it is the

spiral or the grid of the torture-rack or prison cell, the simpler the

labyrinth, the harder it is to escape from it. of expression. It is impossible to overlook the

omnipresent exploration of the horrors of totalitarianism evident in

Julio Antonio’s work from its beginnings. It is also important to

understand that denouncing tyranny, particularly communism in his

native Cuba, serves as a historical context for works of art which live

complex lives in our minds. The mouth-spiral as stage generates an

exchange between the wave-like serrated blades and the molar-figures,

grotesque, vomiting, screaming, distatiorial – caricatures of the

tyrante in olive-green fatigues as well as of his mindless

collaborators that fill the hurricane-decibel plazas. Whether it is the

spiral or the grid of the torture-rack or prison cell, the simpler the

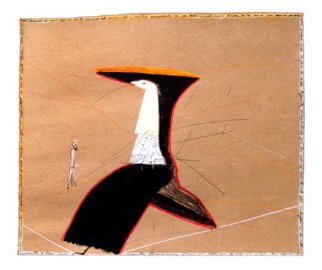

labyrinth, the harder it is to escape from it.Another dialogue between images unveils more of Julio Antonio’s imagination at work. Masks and kites, especially in paintings from the late 80’s, enable the artist to appropriate aspects of Afro-Cuban animism. The specific rituals or deities are not important; the notion that spiritual forces inhabit inanimate objects is. This is a period of Julio Antonio’s work which is also marked by an exuberant textural expression, giving spirals and masks alike a thundering sensorial immediacy. The same duality between centrifugal and centripetal images emerges here, kites and masks respectively. Both kites and masks beckon forces to animate them – wind or personality. Both are rendered in a state between expectation and fulfillment, as stages turned into objects awaiting the beginning of the play. This tension recalls the mythic link between spirit and air, but more importantly, it focuses on the synecdochic nature of the two images. The mask projects personality theatrically, but only because it is a miniature theater in itself. The kite is a tethered sail that makes visible the otherwise invisible action of the wind, but forbidden the functionality of the sail, the kite simply expresses a force of nature by slightly resisting it – it is as theatrical in its thingness as is the mask. Both are  contemporary,

aesthetic and non-ritualistic expressions, then, of the concept of

animism. contemporary,

aesthetic and non-ritualistic expressions, then, of the concept of

animism.In the mid-90’s and since, Julio Antonio’s work moved beyond the painterly and gestural density of his previous style. In some works, the artist has adhered corrugated surfaces, but mostly these are spare works, conceived as drawings even when realized on canvas. They are marked by a thin language, and a freer use of open space produced works which are more overtly theatrical. Surrounding the edges are words, not daggers, although the epigrammatic utterances are often biting. Sketchy figures, at times directly allusive to the nightmare of Cuba under Castro, and other times Beckett-like in their bare-boned presence, are enthroned in spaces whose textural neutrality functions like a limelight. Or the searing light of analysis, operating rooms, and microscopes. It is, for all its simplicity, a space defined as luminous parenthesis in which a setting – sketched before its essence could escape into drama and art – along with one or two characters and a written thought converge. These images have crafted their own sense of dramatic moment, an en passant invitation to a Gordian enigma. Poignant but not urgent, iron but not satirical, succinct but not prescriptive, the language captures the flavors of the quotidian and the philosophical, the narrative and the absurd with equal ease. Forms that function as containers – coffins, wagons, beds – abound. Among these, the most provocative and playful is the BBQ. It recalls the funerary urn, the womb, the chalice and the baptismal font, even the soup caldrons of Afro-Cuban ritual. The BBQ’s are inhabited by austere, fragile, or arcanely robed figures whose skeletons can be seen through the garments. They are the ultimate synecdochic heroes, after all. Tyrant, prophet, and survivor. Witness, oppressor, and poet. The human panoply whose characters cannot free themselves from each other, but each must be the icon of a humanity, and this they call condition, and with this we populate the plot-hungers of our minds and the purpose-seeking impulses of our destinies. Julio Antonio's work Roberts J. Sindelir, Director Galleries and Visual Arts Programs Miami-Dade Community College It has been said of the work of Julio Antonio that it represents the current state of the evolution of Cuban art as it would look if Fidel Castro had not intervened in the island’s history. We will, of course,  never know if this is true. Evolution has never waged

its relentless process in a vacuum, so we must accept the impact of

that phenomenon on today’s imagery as we would accept the reality of

flood, famine or plague. The real art goes on. It is neither

better nor worse, but it is changed. never know if this is true. Evolution has never waged

its relentless process in a vacuum, so we must accept the impact of

that phenomenon on today’s imagery as we would accept the reality of

flood, famine or plague. The real art goes on. It is neither

better nor worse, but it is changed.Celebrated as a motif central to a body of paintings, the kite is a simple and joyful object. However, neither its selection here as subject matter, nor the free manner in which it is rendered should be construed as the work of a naïve artist. Julio Antonio is, in fact, a classically trained artist who for a time also utilized his education for the teachings of others. In similar fashion, the appearance in his paintings of forms which show an affinity for the orishas of Santería does not indicate that he is a practitioner of that religion, or that he is portraying the folkloric tales which enrich the history of his birthplace. In the conventionally Catholic home in which he was raised, he had as a child only a little uneasy contact with the Afro-Cuban religion, and that as a result of some curiosity on the part of his mother.  Having disposed then of the easy ways to deal with Julio Antonio’s

paintings, we are forced to confront them more thoughtfully and openly.

What are they actually about, and why do they look the way they do? The

lavish texture is an immediate attraction. There is an obvious love of

paint and of the way it looks on canvas. There is no hesitation or

timidity in its application. The younger layers recline upon,

reinforce, consolidate, complement, but do not supplant the previous

ones, and the forms emerge.

Having disposed then of the easy ways to deal with Julio Antonio’s

paintings, we are forced to confront them more thoughtfully and openly.

What are they actually about, and why do they look the way they do? The

lavish texture is an immediate attraction. There is an obvious love of

paint and of the way it looks on canvas. There is no hesitation or

timidity in its application. The younger layers recline upon,

reinforce, consolidate, complement, but do not supplant the previous

ones, and the forms emerge.If the application of the paint is instinctive, the selection of the forms which float to the surface is rational. How otherwise would the artist know their names (Formas Punzantes, Formas Milagrosas, Figura con Papalote, ect.), and how know which to  permit to stay? These are not non-objective paintings,

and the artist does not deny the recognizability of the images. The

kites may be a metaphor for displaced Cuban people necessarily

anchored, as kites must be to stay aloft, by their ties to their

homeland. The island can be found in many of the paintings, drawn in

perspective, and floating somewhere in the background. permit to stay? These are not non-objective paintings,

and the artist does not deny the recognizability of the images. The

kites may be a metaphor for displaced Cuban people necessarily

anchored, as kites must be to stay aloft, by their ties to their

homeland. The island can be found in many of the paintings, drawn in

perspective, and floating somewhere in the background.The kites may also assume the faces of African masks or those of the Melanesian Islands. These images reside in Julio Antonio’s memory bank, as do the recollections of work by Dubuffet, Ensor, the German Expressionists and the Fauves, whom he admires. He does not, however, begin a painting with the intention of emulating any previously created form. The cumulative vocabulary is merely concentrated on the task of expressing his own ideas. The forms thus evolved may result in multiple meanings. Kites apparently resting on drums may in fact express aggressive dentition. The skeleton of a kite may strongly resemble on of a human, and the works taken as a whole may mirror the viewers experience, perceptions and expectations. |