El primer Centenario del Templete

Mario Lescano Abella

MCCMXXVIII MCMXXVIII

(fragmento)

La ceiba memorable

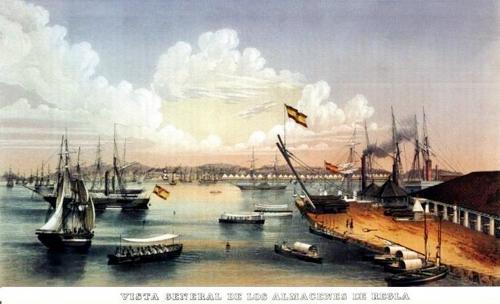

Fundación de la ciudad de la Habana – La primera misa y el primer cabildo se celebran a la sombra de una frondosa ceiba. – Lo que cuenta la tradición. – Reparos de la crítica histórica. – Se esteriliza el árbol legendario. – Cargos contra el gobernador Cagigal. – La erección de una pilastra conmemorativa.

Esta nuestra ciudad de San Cristóbal de la Habana – que es hoy la alegre y cosmopolita capital de la República – fue fundada por Diego Velázquez el día 25 de julio de 1515, festividad de San Cristóbal, en la costa Sur de la Isla de Cuba, cerca de la boca del río Onicajinal, que desagua en la ensenada de Batabanó. A fines del año siguiente se le trasladó a la costa Norte, junto al puerto que Sebastián de Ocampo hubo de denominar Carenas, cuando fondeó y carenó en él sus dos frágiles y gallardas carabelas.

Esta nuestra ciudad de San Cristóbal de la Habana – que es hoy la alegre y cosmopolita capital de la República – fue fundada por Diego Velázquez el día 25 de julio de 1515, festividad de San Cristóbal, en la costa Sur de la Isla de Cuba, cerca de la boca del río Onicajinal, que desagua en la ensenada de Batabanó. A fines del año siguiente se le trasladó a la costa Norte, junto al puerto que Sebastián de Ocampo hubo de denominar Carenas, cuando fondeó y carenó en él sus dos frágiles y gallardas carabelas.

A poco de fundada se la dotó de un Ayuntamiento, colocándosela bajo el mando de un delegado de Velázquez, Pedro Barba, que ostentaba el título de teniente-a-guerra. Y asegura la tradición, con todos sus prestigios venerables, que junto al puerto, a la sombra de una hermosa ceiba, se dijo la primera misa y se celebró el primer cabildo. La crítica histórica, a este respecto, se muestra llena de reparos. Cronista ha habido – nos referimos al erudito Dr. Manuel Pérez Beato – que luego de negar el hecho, consigna este otro extremo: “Allí sí hubo una ceiba pero la cual en vez de veneración, le guardarían horror los vecinos de la villa porque en ella se azotaban a los que caían en pena por alguna causa, como evidencia el acta municipal de 8 de febrero de 1556”. (Inscripciones cubanas de los siglos XVI, XVII y XVIII. – Habana. – 1915.) A la postre la afirmación habría que probarla cumplidamente para no destruir, sin embargo, el bello y amable recuerdo; que no basta negar las leyendas para condenarlas a muerte. La historia sería un libro muy árido, sin ese gran poeta que es el pueblo y se encarga, a cada paso, de adornarla con remembranzas más o menos ciertas, pero casi siempre felices.

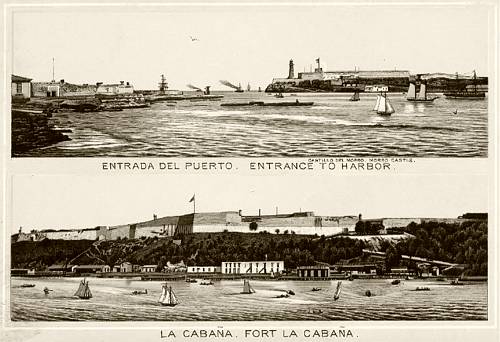

La ceiba precolombina, desafiando el furor de los huracanes tropicales y resistiendo a la hostil impiedad de los hombres, pudo conservarse hasta el año 1753 en que, gobernando la isla el capitán Francisco Cagigal de la Vega, ordenó fuera reemplazada por un pobre monumento en forma de pilastra triangular, de nueve varas de alto. La simbólica ceiba había desaparecido. ¿Cómo? Afirman unos que se esterilizó por vieja o maltratada. Otros acusan al gobernador Cagigal de su destrucción. Llegó a decirse que el Virrey, enojado porque el árbol le impedía contemplar el panorama del puerto y el arribo de los bajeles españoles, fue su verdugo y por su orden hacha vulgar le derribó en tierra. Aseguróse, también, que el representante de la Gran Bretaña en la Habana – a lo que parece el único que en aquellos días sospechaba el valor del árbol – adquirió un pedazo con destino al Museo Británico; y que el resto, comprado como leña por anónimos industriales, fue quizá a alimentar los hornos de los panaderos de entonces para cocer el pan destinado al impío vecindario de la ciudad.

pudo conservarse hasta el año 1753 en que, gobernando la isla el capitán Francisco Cagigal de la Vega, ordenó fuera reemplazada por un pobre monumento en forma de pilastra triangular, de nueve varas de alto. La simbólica ceiba había desaparecido. ¿Cómo? Afirman unos que se esterilizó por vieja o maltratada. Otros acusan al gobernador Cagigal de su destrucción. Llegó a decirse que el Virrey, enojado porque el árbol le impedía contemplar el panorama del puerto y el arribo de los bajeles españoles, fue su verdugo y por su orden hacha vulgar le derribó en tierra. Aseguróse, también, que el representante de la Gran Bretaña en la Habana – a lo que parece el único que en aquellos días sospechaba el valor del árbol – adquirió un pedazo con destino al Museo Británico; y que el resto, comprado como leña por anónimos industriales, fue quizá a alimentar los hornos de los panaderos de entonces para cocer el pan destinado al impío vecindario de la ciudad.

[…..]

En nuestros días ha defendido la memoria de Cagigal de aquel atentado, el Dr. Eugenio Sánchez de Fuentes en su libro “Cuba monumental, estatuaria y epigráfica” (Habana, 1916) sosteniendo la opinión de que el árbol fue derribado por un huracán o se esterilizó a consecuencia de los trabajos realizados, cerca de él, para la erección de la pilastra. “¿Cómo es posible asegurar – arguye – que Cagigal de la Vega, por la satisfacción de un mero capricho personal, inocente inclusive, desoyera la voz serena de la razón y realizara semejante atentado a la historia patria, prescindiendo no ya de nuestro ayuntamiento, representación legítima de la ciudad, que de seguro al conocer su propósito, se hubiera realmente opuesto, así como su procurador el ilustre don Manuel Felipe de Arango; sino de justísimos cargos que contra él, todo nuestro pueblo, hubiera formulado cívicamente, por tan bárbaro proceder? Además, es cosa averiguada, con absoluta certeza, que poco tiempo después de la erección del obelisco, tres nuevas ceibas fueron sembradas. Y a la verdad, la lógica inflexible de los hechos, nos hace deducir que el supuesto sacrificio de la precolombina, resultó completamente inútil toda vez que con la columna y el sembrado de los nuevos árboles, el campo de la visualidad quedó mucho más limitado que antes.”

[…..]

La inculpación hecha al gobernador Cagigal no tiene ningún fundamento sólido. Lo de la adquisición por un cónsul extranjero, de un fragmento de la ceiba derribada, se registra en algunos papeles viejos. Por ejemplo, el doctor Domingo Rosain en su extraño libro “Necrópolis de la Habana. – Historia de los cementerios de esta ciudad” (Habana 1875) manifiesta: “En 1753 derribada la que existía (la ceiba) sus fragmentos se vendieron para leña, comprando algunos el cónsul de los Estados Unidos para el Museo de Washington”. ¡El cronista olvida que hasta 1783 dominó Inglaterra en la América del Norte!

La inculpación hecha al gobernador Cagigal no tiene ningún fundamento sólido. Lo de la adquisición por un cónsul extranjero, de un fragmento de la ceiba derribada, se registra en algunos papeles viejos. Por ejemplo, el doctor Domingo Rosain en su extraño libro “Necrópolis de la Habana. – Historia de los cementerios de esta ciudad” (Habana 1875) manifiesta: “En 1753 derribada la que existía (la ceiba) sus fragmentos se vendieron para leña, comprando algunos el cónsul de los Estados Unidos para el Museo de Washington”. ¡El cronista olvida que hasta 1783 dominó Inglaterra en la América del Norte!

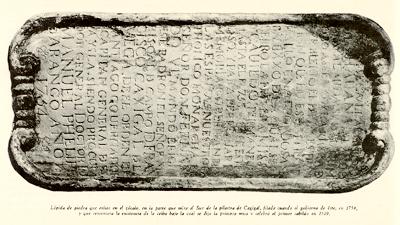

En la pilastra, sobre la lápida del zócalo, en la parte que mira al Sur, se fijó la siguiente inscripción: “FUNDOSE LA VILLA (OY CIUDAD) DE LA HAVANA A LA RIVERA DE ESE PUERTO EL DE 1519. ES TRADICION QUE EN ESTE SITIO SE HALLO UNA FRONDOSA SEIBA BAXO DE LA CUAL SE CELEBRO LA PRIMERA MISSA Y CAVILDO: PERMANECIO HASTA EL DE 1753 QUE SE ESTERILISO; Y PARA PERPETUAR LA MEMORIA GOBERNANDO LAS ESPAÑAS NUESTRO CATHOLICO MONARCHA EL SEÑOR DON FERNANDO VI MANDO EREGIR ESTE PADRON EL SEÑOR MARISCAL DE CAMPO DON FRANCISCO CAXIGAL DE LA VEGA DE EL ORDEN DE SANTIAGO GOBERNADOR Y CAPITAN GENERAL DE ESTA YSLA: SIENDO PROCURADOR GENERAL DOCTOR DON MANUEL PHELIPE DE ARANGO AÑO DE 1 7 5 4

LA VEGA DE EL ORDEN DE SANTIAGO GOBERNADOR Y CAPITAN GENERAL DE ESTA YSLA: SIENDO PROCURADOR GENERAL DOCTOR DON MANUEL PHELIPE DE ARANGO AÑO DE 1 7 5 4

En la cara de la base del pilar que mira al Norte se grabó, según Pezuela, esta otra leyenda:

SISTE GRADUM VIATOR ORNAT HUNC LOCUM ARBOS CEIBA FRONDOSA POTIUS DIXERIM PRIMEVAE CIVI TATIS PRUDENTIAE RELIGIONIS PRIMEVAE MEMORABILE SIGNUM: SIQUI DEM EJUS SUB UMBRA APRIME HAC IN URBE INMOLATUS SALUTIS AUTOR. HABITUS PRIMO PRUDENTUM DECURIONUM SENATUS DUOBUS PLUS AB IN SAECULIS PERPETUA TRADITIONE HABEBATUR. CESSIT TAMEN AETATI. INTUERE IGITUR, ET NE PAREAT IN POSTERUM HABANENSEM FIDEM. ASPICIES IMAGINEM SUPRA PETRAM FUNDATAN HODIE NIMIRUM ULT. MENSIS NOVEMBRIS ANNO MDCCLIV.

La traducción la ha dado el doctor Juan Miguel Dihigo, latinista y catedrático de Nuestra Universidad, que le hizo a la leyenda ciertas modificaciones de las que luego nos ocuparemos. Dice así en castellano: “Detén el paso caminante, adorna este sitio un árbol, una ceiba frondosa, más bien diré signo memorable de la prudencia y antigua religión de la joven ciudad, pues ciertamente bajo su sombra fue inmolado solemnemente en esta ciudad el autor de la salud. Fue tenida por primera vez la reunión de los prudentes concejales hace ya más de dos siglos: era conservado por una tradición perpetua; sin embargo cedió al tiempo. Mira pues y no perezca en lo porvenir la fe habanera. Verás una imagen hecha hoy en la piedra, es decir el último de Noviembre en el año 1754.”

La traducción la ha dado el doctor Juan Miguel Dihigo, latinista y catedrático de Nuestra Universidad, que le hizo a la leyenda ciertas modificaciones de las que luego nos ocuparemos. Dice así en castellano: “Detén el paso caminante, adorna este sitio un árbol, una ceiba frondosa, más bien diré signo memorable de la prudencia y antigua religión de la joven ciudad, pues ciertamente bajo su sombra fue inmolado solemnemente en esta ciudad el autor de la salud. Fue tenida por primera vez la reunión de los prudentes concejales hace ya más de dos siglos: era conservado por una tradición perpetua; sin embargo cedió al tiempo. Mira pues y no perezca en lo porvenir la fe habanera. Verás una imagen hecha hoy en la piedra, es decir el último de Noviembre en el año 1754.”

Como elementos decorativos de la pilastra figuraban, en el primer frente del triángulo que mira al naciente, un relieve del tronco de la primitiva ceiba, seca, con las ramas cortadas y sin follaje alguno; en lo cimero, como para que protegiese la ciudad, una imagen de Nuestra Señora del Pilar, de construcción gótica como apunta un documento oficial de a principios del pasado siglo.

tronco de la primitiva ceiba, seca, con las ramas cortadas y sin follaje alguno; en lo cimero, como para que protegiese la ciudad, una imagen de Nuestra Señora del Pilar, de construcción gótica como apunta un documento oficial de a principios del pasado siglo.

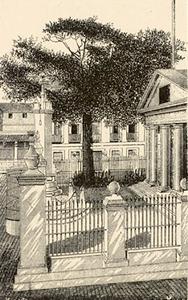

No bastó a los habaneros de entonces el testimonio de la piedra. Parece que  el recuerdo de la dulce ceiba legendaria les preocupaba. Lo cierto es que unos años más tarde – entre 1755 y 1757, según Sánchez de Fuentes – el Ayuntamiento acordó plantar tres ceibas alrededor del monumento. Dos de ellas perecieron al poco tiempo. La que sobrevivió fue víctima, en 1827, de un crimen que, sin embargo, no alarmó a nadie. ¡Y el señor Sánchez de Fuentes que cree que la ciudad se hubiera cívica e inteligentemente opuesto al deseo de Cagigal, caso que este hubiese ordenado, por razones visuales o de otra especie, el derribo del árbol venerable que cobijó a Diego Velázquez y a sus valientes! En 1827, cuando se llevaba a cabo la construcción del Templete, el Cabildo acordó derribar esa ceiba, castigándola por bella y por frondosa. Se estimó que sus fuertes y hondas raíces podían poner en peligro la solidez de la nueva construcción. El hacha municipal consumó su obra con aplausos. Al terminarse el Templete, en el año siguiente, el Ayuntamiento dio órdenes para que se sembrasen nuevos árboles: ceibas, álamos, palmas. El capitán Andrés de Acosta los trajo de una finca denominada “María de Ayala”, precisamente donde está enclavado hoy el barrio de Luyanó. La que existe es una de esas ceibas que, esbelta e impávida, ha resistido a los sucesos alegres y tristes, grandes y pequeños. Otras, que se sembraron en 1873, tuvieron efímera vida: dos lustros, que nada son si se tiene en cuenta que estos gigantes contemplan el paso de los siglos.

el recuerdo de la dulce ceiba legendaria les preocupaba. Lo cierto es que unos años más tarde – entre 1755 y 1757, según Sánchez de Fuentes – el Ayuntamiento acordó plantar tres ceibas alrededor del monumento. Dos de ellas perecieron al poco tiempo. La que sobrevivió fue víctima, en 1827, de un crimen que, sin embargo, no alarmó a nadie. ¡Y el señor Sánchez de Fuentes que cree que la ciudad se hubiera cívica e inteligentemente opuesto al deseo de Cagigal, caso que este hubiese ordenado, por razones visuales o de otra especie, el derribo del árbol venerable que cobijó a Diego Velázquez y a sus valientes! En 1827, cuando se llevaba a cabo la construcción del Templete, el Cabildo acordó derribar esa ceiba, castigándola por bella y por frondosa. Se estimó que sus fuertes y hondas raíces podían poner en peligro la solidez de la nueva construcción. El hacha municipal consumó su obra con aplausos. Al terminarse el Templete, en el año siguiente, el Ayuntamiento dio órdenes para que se sembrasen nuevos árboles: ceibas, álamos, palmas. El capitán Andrés de Acosta los trajo de una finca denominada “María de Ayala”, precisamente donde está enclavado hoy el barrio de Luyanó. La que existe es una de esas ceibas que, esbelta e impávida, ha resistido a los sucesos alegres y tristes, grandes y pequeños. Otras, que se sembraron en 1873, tuvieron efímera vida: dos lustros, que nada son si se tiene en cuenta que estos gigantes contemplan el paso de los siglos.

La Habana: Sindicato de Artes Gráficas, 1928

Doña Lola, idealista y ambiciosa, nos decía que el pájaro caribeño somos las dos alas. En estos días, cuando tenemos que recoger alas, quizá nos valga más la pena ir de lo más pequeño para llegar a esa totalidad. Por eso digo que tú y yo somos las dichosas alas, y así lo digo para que poco a poco lleguemos a alcanzar lo que Doña Lola quería. Le doy tres vueltas a la ceiba para que así sea. Acompáñame.

Efraín Barradas

Con una invitación así, y con la promesa de reencontrar tantos amigos en el tiempo, ¿cómo faltar a la cita de Iroko, la Espaciosa, la Madre? "El Monte tiene su ley", nos enseñó Lydia Cabrera. Gracias a La Habana Elegante por recordarnos a sus hijas e hijos que debemos cumplir el mandato de su árbol sagrado.

Madelín Cámara

Un Monumento y una Sugestiva Ceiba

María Teresa Villaverde Trujillo

Cada 15 de noviembre, hacia la medianoche, visitamos el monumento El Templete y su Ceiba para festejar otro aniversario de la fundación de San Cristóbal de La Habana, hecho histórico realizado en 1519 por el conquistador español y gobernador de la isla Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar. El nombre de la entonces villa, asignada asi por el lugarteniente del gobernador general Pánfilo de Narváez surgió de la unión del nombre del santo patrón y del nombre de un cacique taino de aquella área. También, los que hemos vivido cerca de la Ceiba sabemos lo difícil que es olvidar este árbol, representativo del nacimiento de mi ciudad natal, centro de las actividades en la época colonial.

Cada 15 de noviembre, hacia la medianoche, visitamos el monumento El Templete y su Ceiba para festejar otro aniversario de la fundación de San Cristóbal de La Habana, hecho histórico realizado en 1519 por el conquistador español y gobernador de la isla Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar. El nombre de la entonces villa, asignada asi por el lugarteniente del gobernador general Pánfilo de Narváez surgió de la unión del nombre del santo patrón y del nombre de un cacique taino de aquella área. También, los que hemos vivido cerca de la Ceiba sabemos lo difícil que es olvidar este árbol, representativo del nacimiento de mi ciudad natal, centro de las actividades en la época colonial.

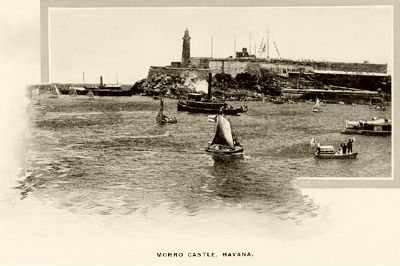

Por mandato de los reyes durante el siglo XVII se nombró a La Habana "Llave del Nuevo Mundo y antemural de las Indias”

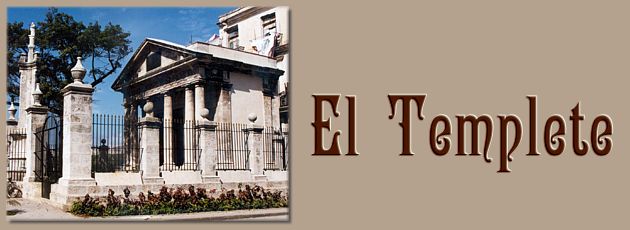

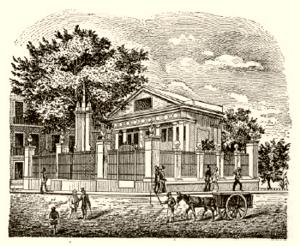

El Templete fue construido a principio del siglo XIX, en el mismo sitio donde celebraron al pie de una Ceiba la primera misa y la reunión del primer cabildo presidido por Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, - entonces Teniente Gobernador de la isla-, en la costa norte de La Habana en 1519. Fue una obra del coronel de ingenieros el cubano Antonio María de la Torre y Cardenas bajo los auspicios del capitán general y gobernador Francisco Dionisio Vives, y el obispo de La Habana Juan José Díaz de Espada y Fernández de Landa. El monumento adopta la forma de un singular templo dórico, sobre un cuadrilongo regular de treinta y  dos varas de este a oeste y de veintidós de norte a sur, cercado el monumento por una enverjadura de hierro que termina en lanzas de bronce, apoyadas sobre globos del mismo metal. Mide doce varas de frente y ocho y media por los dos costados así como 11 de alto, compuesto de un arquitrabe de seis columnas de capiteles dóricos y zócalos áticos y cuatro pilastras en los costados. La portada de hierro que pesa dos mil libras rueda sobre ejes de bronce, coronándose con un escudo de cinco pies de altura en cuya orla aparece la siguiente frase: “La siempre fidelísima ciudad de La Habana”.

dos varas de este a oeste y de veintidós de norte a sur, cercado el monumento por una enverjadura de hierro que termina en lanzas de bronce, apoyadas sobre globos del mismo metal. Mide doce varas de frente y ocho y media por los dos costados así como 11 de alto, compuesto de un arquitrabe de seis columnas de capiteles dóricos y zócalos áticos y cuatro pilastras en los costados. La portada de hierro que pesa dos mil libras rueda sobre ejes de bronce, coronándose con un escudo de cinco pies de altura en cuya orla aparece la siguiente frase: “La siempre fidelísima ciudad de La Habana”.

Las obras culminaron con su inauguración el 19 de marzo de 1828, en homenaje a Josefa Amalia de Sajonia, esposa de Fernando VII. Dos grandes lienzos adornaron su interior, uno representando la primera misa ofrecida por el Padre de Las Casas y el otro el primer cabildo, ambas obras del pintor frances Jean Baptiste Vermay.

Fuera de la edificación aparece un obelisco de tres caras, llamado Cajigal por ser el apellido del gobernador Francisco Cajigal de la Vega, quién ordenó construirla en 1754 cuando la Ceiba dejó de sostenerse en pie. La columna sostenía una imagen de Nuestra Señora del Pilar, patrona de los navegantes españoles. A la antigua imagen religiosa, sustituyó otra de la Virgen, de una vara de alto sobre un pilar de tres cuartas, en cuyo centro está trazada la Cruz de Aragón, con una inscripción que dice: “Memoria inmortal a Francisco Dionisio Vives y Planes, teniente general de los Reales Ejércitos, benemérito de la patria. Año de mil ochocientos veintidós”.

general de los Reales Ejércitos, benemérito de la patria. Año de mil ochocientos veintidós”.

En su base se encuentra un busto de mármol del Adelantado Don Hernando de Soto, primer gobernador de la villa; y en ella hay una inscripción en latín, casi borrada, que traducida dice:

"Detén el paso, caminante, adorna este sitio un árbol, una ceiba frondosa, más bien diré signo memorable de la prudencia y antigua religión de la joven ciudad, pues ciertamente bajo su sombra fue inmolado solemnemente en esta ciudad el autor de la salud. Fue tenida por primera vez la reunión de los prudentes concejales hace ya más de dos siglos: era conservado por una tradición perpetua: sin embargo, cedió al tiempo. Verás una imagen hecha hoy en la piedra, es decir el último de noviembre en el año 1754"

Dentro de los límites del monumento, cerrado por las verjas que protegen el Templete, se localiza un busto de mármol de Cristóbal Colón; y se mantiene una frondosa Ceiba en medio del pequeño jardin. La original Ceiba fue destruida por un ciclon; mas tarde otra Ceiba regresó a su lugar y, según narraciones, al ésta secarse, una tercera es la que ocupa actualmente su destinado espacio. El pavimento de El Templete es de mármol blanco.

En el interior del Templete se encuentra un triptico - cuyo lienzo central fue pintado tiempo despues a la inauguración del monumento – representando la primera misa en el acto de bendición del lugar en presencia del Capitán General, el primer consejo de gobierno y la construccion del Templete, apareciendo en ellos las figuras de las autoridades españolas de la época. Es un histórico triptico que dejó para la posteridad unas excelentes estampas de coloridos acontecimientos.

Las fotos que acompañan este artículo nos fueron cedidas gentilmente por el prof. Paul Barret, de la Universidad de Texas, y no pueden reproducirse sin su consentimiento.

Noviembre de 2010

Querido Francisco:

Una vez más, un aniversario de nuestra querida Habana nos une. Te enviamos un abrazo y saludos a todos los que participamos en este ritual, justificado por nuestro cariño hacia nuestra maltratada ciudad. Y con aumentado cariño, otro abrazo para ti por regalarnos otra oportunidad de vernos todos otra vez al pie de la ceiba.

Aymara y Micael Avalos

Miami

La foto es en la sacristía de la Iglesia del Espíritu Santo el 4 de marzo de 1976, en el bautizo de Ariadna Prats García. Al fondo aparece María Luisa Bautista; al frente hay un busto de Dante. Dante, Lezama, dos escritores que sufrieron el exilio; el cubano en su propia tierra, desde 1971 hasta su muerte. En este 491 aniversario de La Habana inmortal e inmoral, Lezama como autor de Muerte de Narciso y Virgilio Piñera, autor de La isla en peso, le dan la vuelta a la ceiba aciclonada de Oppiano Licario, se unen al fantasma de Hernando de Soto para repetir una frase escrita por Lezama en la primera carta a su hermana Eloísa (abril de 1961), a la que nunca volvería a ver: "Quiera Dios que se restablezca la armonía".

La foto es en la sacristía de la Iglesia del Espíritu Santo el 4 de marzo de 1976, en el bautizo de Ariadna Prats García. Al fondo aparece María Luisa Bautista; al frente hay un busto de Dante. Dante, Lezama, dos escritores que sufrieron el exilio; el cubano en su propia tierra, desde 1971 hasta su muerte. En este 491 aniversario de La Habana inmortal e inmoral, Lezama como autor de Muerte de Narciso y Virgilio Piñera, autor de La isla en peso, le dan la vuelta a la ceiba aciclonada de Oppiano Licario, se unen al fantasma de Hernando de Soto para repetir una frase escrita por Lezama en la primera carta a su hermana Eloísa (abril de 1961), a la que nunca volvería a ver: "Quiera Dios que se restablezca la armonía".

José Prats

Dejo junto a la ceiba fiel de La Habana Elegante, guardiana de la fe habanera, mis votos por la salvación de la ciudad, aunque solo sea en el daguerrotipo de la memoria.

Armando Sandoval

Estas páginas son un oasis de buen gusto y esmero. En este 491 Aniversario pediré en la ceiba un mejor destino para mi Patria, familiares y amigos.

Laureano

Directorio criticón de la Habana (1883)

Juan Franqueza

Fragmentos

La calle de la Muralla

Estamos en la más célebre vía de la Habana. Su verdadero nombre es Ricla, que fue título condal de uno de los capitanes generales que gobernaron la isla; pero todo el mundo le dice de la Muralla y así tenemos que llamarla nosotros, poco afectos tambien a recordar magnates. No se explica cómo se hacen las cosas inmateriales tan respetables como las entidades humanas, y por qué un conjunto de piedras a los lados de una calle, imprimen respeto y toda clase de fenómenos mentales entre un pueblo despreocupado y casi transitorio como lo es el nuestro; mas es el caso que así sucede y que la calle de la Muralla es la entidad mas respetable e influyente de la capital de la Gran Antilla. Miles de individuos se han encumbrado, ya por medio del dinero ya por el de las letras o el de la milicia, y el tiempo los ha derribado luego como castillos de naipes, esparciendo sus recuerdos entre el polvo del olvido; pero la calle de la Muralla pasa de vicisitud en vicisitud, de tormenta en tormenta, y su tipo y su prestigio se mantienen intactos sin que haya ciclón que la melle, y antes al contrario, parece rejuvenecerse a cada desastre que conmueven los cimientos del comercio o de la sociedad. ¿En qué estriba este fenómeno? Probable es que nadie lo explique satisfactoriamente, porque el argumento de la aotigüedad lo destruyen algunos ejemplos de cosas viejas que cayeron ya desplomadas por el espíritu innovador del siglo. El caso es que los establecimientos de la calle de que venimos hablando, muestran una solidez en los negocios de que carecen los de las otras, mas bulliciosas y nuevas, y se parecen al árbol secular de los autonomistas vizcainos, que no lo deshojan ni las revoluciones europeas yni aun la misma dinamita que produce espanto en todas partes.

Estamos en la más célebre vía de la Habana. Su verdadero nombre es Ricla, que fue título condal de uno de los capitanes generales que gobernaron la isla; pero todo el mundo le dice de la Muralla y así tenemos que llamarla nosotros, poco afectos tambien a recordar magnates. No se explica cómo se hacen las cosas inmateriales tan respetables como las entidades humanas, y por qué un conjunto de piedras a los lados de una calle, imprimen respeto y toda clase de fenómenos mentales entre un pueblo despreocupado y casi transitorio como lo es el nuestro; mas es el caso que así sucede y que la calle de la Muralla es la entidad mas respetable e influyente de la capital de la Gran Antilla. Miles de individuos se han encumbrado, ya por medio del dinero ya por el de las letras o el de la milicia, y el tiempo los ha derribado luego como castillos de naipes, esparciendo sus recuerdos entre el polvo del olvido; pero la calle de la Muralla pasa de vicisitud en vicisitud, de tormenta en tormenta, y su tipo y su prestigio se mantienen intactos sin que haya ciclón que la melle, y antes al contrario, parece rejuvenecerse a cada desastre que conmueven los cimientos del comercio o de la sociedad. ¿En qué estriba este fenómeno? Probable es que nadie lo explique satisfactoriamente, porque el argumento de la aotigüedad lo destruyen algunos ejemplos de cosas viejas que cayeron ya desplomadas por el espíritu innovador del siglo. El caso es que los establecimientos de la calle de que venimos hablando, muestran una solidez en los negocios de que carecen los de las otras, mas bulliciosas y nuevas, y se parecen al árbol secular de los autonomistas vizcainos, que no lo deshojan ni las revoluciones europeas yni aun la misma dinamita que produce espanto en todas partes.

La calle de la Muralla es en lo inteetual ylo moral como una república independiente y altanera que no recibe los hálitos de sus vecinos, sino que antes al contrario impone sus teorías y su voluntad al resto de la población. Cuando acontece algo en la Península que influye en la conciencia nacional, las miradas se dirigen al que llamaremos baluarte, indagando el pensamiento que domina, ya para imitar sus manifestaciones ya para saber a qué atenerse. De allí parten las muestras de satisfacción o de indiferencia por los acontecimientos sociales o políticos de la madre patria, y cuando la maayoría de la población difiere, no se le contradice sino se le respeta. No siempre la calle de la Muralla ha sido simpática por sus demostraciones; imperan por tradición en ese centro comercial teorías que han dejado de ser populares y que allí se perpetúan por causas impenetrables. Es lástima que esto suceda, porque la calle es digna de toda clase de consideraciones, y ha puesto a gran altura el pabellón de su generosidad en circunstancias oportunas. Un poco de transigencia, un contacto más espiritual con el resto de la población, completarían su gloria.

La calle de la Muralla es en lo inteetual ylo moral como una república independiente y altanera que no recibe los hálitos de sus vecinos, sino que antes al contrario impone sus teorías y su voluntad al resto de la población. Cuando acontece algo en la Península que influye en la conciencia nacional, las miradas se dirigen al que llamaremos baluarte, indagando el pensamiento que domina, ya para imitar sus manifestaciones ya para saber a qué atenerse. De allí parten las muestras de satisfacción o de indiferencia por los acontecimientos sociales o políticos de la madre patria, y cuando la maayoría de la población difiere, no se le contradice sino se le respeta. No siempre la calle de la Muralla ha sido simpática por sus demostraciones; imperan por tradición en ese centro comercial teorías que han dejado de ser populares y que allí se perpetúan por causas impenetrables. Es lástima que esto suceda, porque la calle es digna de toda clase de consideraciones, y ha puesto a gran altura el pabellón de su generosidad en circunstancias oportunas. Un poco de transigencia, un contacto más espiritual con el resto de la población, completarían su gloria.

Casi todos los establecimientos que contiene la calle son buenos y algunos esplendorosos. No hay ramo de comercio que deje de estar representado muy dignamente, sobresaliendo entre las tiendas donde se espenden los efectos al menudeo, La Colonial y Mestre y Martinica, grandes fábricas de chocolates; la florería El Ramillete; las locerías La Bomba y La Prueba; La Primavera, taller de modistas; las magníficas platerías de Misa y Lira de Oro; la antiquísima y siempre reputada tienda de paños El Navío; las tiendas de ropas La Perla y la Glorieta Cubana; la librería de Sans; las boticas de Santa Ana y San Julian; el célebre y reputado Palo Gordo, cada día más hermoso; la gran perfumería La Oriental; la galletería y biscochería Inglesa, única aquí en su clase y hasta el popular y excelente café La Victoria, que atrae a multitud de personas de otros barrios por saborear en especial café con leche. Los establecimientos que no hemos mencionado no dejan de ser menos dignos, habiendo magníficos almacenes ce géneros, quincalla, etc., ypara que nada falte a la calle de la Muralla, guarda a la redacción e imprenta del Diario de la Marina, que es el mas antiguo yfloreciente periódico de la Isla ydel que hablaremos en capítulo aparte, pues que también hemos de enterar al lector de la política que hacen este como otros diarios de la capital, para que sepa a qué atenerse cuando los lea, si acaso no les indigesta pronto su monotonía.

Colonial y Mestre y Martinica, grandes fábricas de chocolates; la florería El Ramillete; las locerías La Bomba y La Prueba; La Primavera, taller de modistas; las magníficas platerías de Misa y Lira de Oro; la antiquísima y siempre reputada tienda de paños El Navío; las tiendas de ropas La Perla y la Glorieta Cubana; la librería de Sans; las boticas de Santa Ana y San Julian; el célebre y reputado Palo Gordo, cada día más hermoso; la gran perfumería La Oriental; la galletería y biscochería Inglesa, única aquí en su clase y hasta el popular y excelente café La Victoria, que atrae a multitud de personas de otros barrios por saborear en especial café con leche. Los establecimientos que no hemos mencionado no dejan de ser menos dignos, habiendo magníficos almacenes ce géneros, quincalla, etc., ypara que nada falte a la calle de la Muralla, guarda a la redacción e imprenta del Diario de la Marina, que es el mas antiguo yfloreciente periódico de la Isla ydel que hablaremos en capítulo aparte, pues que también hemos de enterar al lector de la política que hacen este como otros diarios de la capital, para que sepa a qué atenerse cuando los lea, si acaso no les indigesta pronto su monotonía.

Lástima irremediable es la estrechez con que fue construida esta cono todas las demás calles de la sección de lo que fue intramuros de la ciudad, y que no le permita esta causa lucir todo su mérito. Cuando un efecto falte en el resto de los de la población, debe buscarse en la calle de la Muralla y allí es casi seguro encontrarle. Es cuanto podemos decir en obsequio de la respetable vía comercial, tan antigua como sólida, tan independiente como rica, tan generosa como severa. Lástima que no hayan podido ser nuestras alabanzas completas y que las ideas espansivas no hayan penetrado allí a la par que las riquezas. Culpa será de la humanidad que no es perfecta. A nosotros no nos incumbe reprobar nada sobre este punto; la conciencia debe de ser respetada y hemos terminado nuestro capítulo.

Para mis amigos en La Habana y para mi esposa (a la que llevo en el corazón) dejo mi ofrenda en el Templete que nos convoca cada año.

Enrique Domínguez, México

A los redactores de La Habana Elegante, gracias por este memorable paseo y bello homenaje. Mis deseos son de paz y que podamos reunirnos todos los cubanos. Mientras llega ese día, tenemos este árbol que no se seca.

Rosa Emilia Agramonte, Santiago de Chile

Cuando un amigo me recomendó esta revista no podía imaginar que me encontraría con esta sorpresa. La idea de recrear las tres vueltas a la ceiba y convertirla en una verdadera tradición es una de las inciativas que distigue a La Habana Elegante de otras revistas. Me conmueve esa memoria terca que nos recuerda cada año la ciudad. Prometo regresar cada año. Les deseo a todos los habaneros una noche feliz y esperanzada.

Alberto Rodríguez, Miami.

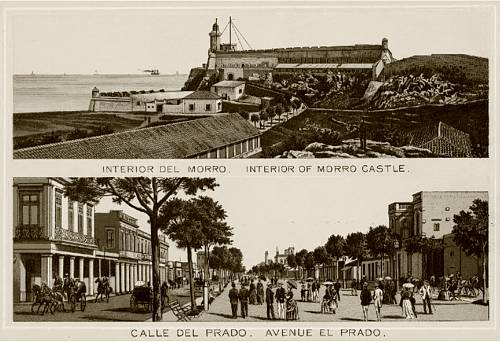

Las alamedas y el Parque

Al salir de las estrechas ypor este motivo calurosas calles, que causan mas sufrimientos que placeres al pedreste que las transita, se ve uno sorprendido al encontrarse en el centro de la ciudad con una espléndida y anchurosa vía bordada de árboles frondosos, que parece algo del Edén con que sueñan los europeos cuando piensan en estos países tropicales, de maravillosa vegetación, descritos con vivos colores, y que arrancaron al descubridor tan concisa como descriptiva frase al contemplar a Cuba: “Es la mas fermosa tierra que los ojos vieron.” Casi todo el ancho de la ciudad está atravesado por la alameda, que tomando nombres distintos segun sus divisiones, comienza en la calle del Príncipe Alfonso, antes calzada del Monte, y termina en el castillo de la Punta a la entrada del puerto. Parque de la India, Parque de Isabel la Católica, Parque Central y Paseo del Prado, son las denominaciones que toma la vía, sin rival no solo en la Habana sino en muchas ciudades de más encopetado tono. Comodidad, fresco y aseo de que se carece entre las calles se encuentran allí reunidos, y gracias a este respiro puede soportar la vida el hombre espansivo, que sin estos lugares le sería penosa.

Al salir de las estrechas ypor este motivo calurosas calles, que causan mas sufrimientos que placeres al pedreste que las transita, se ve uno sorprendido al encontrarse en el centro de la ciudad con una espléndida y anchurosa vía bordada de árboles frondosos, que parece algo del Edén con que sueñan los europeos cuando piensan en estos países tropicales, de maravillosa vegetación, descritos con vivos colores, y que arrancaron al descubridor tan concisa como descriptiva frase al contemplar a Cuba: “Es la mas fermosa tierra que los ojos vieron.” Casi todo el ancho de la ciudad está atravesado por la alameda, que tomando nombres distintos segun sus divisiones, comienza en la calle del Príncipe Alfonso, antes calzada del Monte, y termina en el castillo de la Punta a la entrada del puerto. Parque de la India, Parque de Isabel la Católica, Parque Central y Paseo del Prado, son las denominaciones que toma la vía, sin rival no solo en la Habana sino en muchas ciudades de más encopetado tono. Comodidad, fresco y aseo de que se carece entre las calles se encuentran allí reunidos, y gracias a este respiro puede soportar la vida el hombre espansivo, que sin estos lugares le sería penosa.

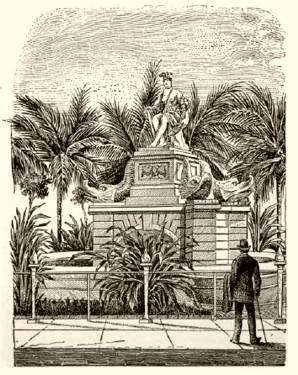

La fuente de mármol quo adorna el parque de la India y que por la obra toma el nombre, es una bella y magnífica escultura y de lo mejor que puede encontrarse en América. Se debe al espíritu patriótico y artístico del Intendente Pinillos, que fue hijo de esta ciudad y a más celoso de su esplendor, cosa que no ha tenido muchos imitadores después. La india Habana que preside la fuente, es un mito, pero recuerda con las formas de la más bella estética a la raza aborígen que cedió el puesto a la íbérica y a la africana, trasplantadas aquí. Es un monumento necesario y reparador, y digno del espíritu poético y caballeresco español. A la verdad que es de lo mas simpático que encierra la Habana y difícilmente encontrarían los hombres de estos tiempos creación que satisfaga mejor.

que cedió el puesto a la íbérica y a la africana, trasplantadas aquí. Es un monumento necesario y reparador, y digno del espíritu poético y caballeresco español. A la verdad que es de lo mas simpático que encierra la Habana y difícilmente encontrarían los hombres de estos tiempos creación que satisfaga mejor.

El parque de Isabel la Católica no tiene nada especial que describir, pues que el arte no ha reclamado desde hace mucho tiempo a nuestros administradores ningún gasto. El centro de este tramo del paseo está adornado con retazos de fuentes viejas, gracias a que los hombres de otras épocas se ocuparon de ernbelleeer su residencia, y algunos restos quedan de lo que adquirieron. Bancos de hierro aunque escasos, brindan descanso al paseante, que encuentra alegría no solo en el coposo verdor de los árboles, sino en el bullicioso pitar de millares de pájaros que se anidan en sus ramas. A uno de los lados se ostenta correcta línea de edificios nuevos, de buen aspecto aunque monótonos en su conjunto por la igualdad y por las gruesas columnas de los portales. El sistema anticuado de construcciones que en la Habana no se reforma da un aspecto melancólico a la ciudad, que contrasta con la alegría del cielo. ¿Para qué tantas piedras? No se ve la ventaja que ofrece ese modo de fabricar ni en la solidez ni en nada. El paradero y depósitos del ferrocarril de Villanueva ocupan el lado opuesto, causando mal efecto y dando pobre idea del espíritu emprendedor de esa Empresa.

Viene despúes el Parque Central, más anchuroso que los demás y verdadero centro donde se esparce el ánimo yse refresca por las noches el cuerpo agobiado por el calor del día. Está bien trazado y mejor alumbrado, pero sin otra cosa digna de alabanza. Han puesto en el centro y precisamente en el sitio que reclama un kiosco y caja armónica para la música, a una estatua de poquísimo mérito artístico, por solo representar a una ex-reina y cuya obra no satisface a la vista siendo rémora de una necesidad. A la entrada de alguno de los otros parques haría buen efecto la estatua, y el kiosco daría mayor lucimiento al Central y a las bandas militares que obsequian con sus conciertos al público, en noches deliciosas que convidan a sentir y a gozar.

Viene despúes el Parque Central, más anchuroso que los demás y verdadero centro donde se esparce el ánimo yse refresca por las noches el cuerpo agobiado por el calor del día. Está bien trazado y mejor alumbrado, pero sin otra cosa digna de alabanza. Han puesto en el centro y precisamente en el sitio que reclama un kiosco y caja armónica para la música, a una estatua de poquísimo mérito artístico, por solo representar a una ex-reina y cuya obra no satisface a la vista siendo rémora de una necesidad. A la entrada de alguno de los otros parques haría buen efecto la estatua, y el kiosco daría mayor lucimiento al Central y a las bandas militares que obsequian con sus conciertos al público, en noches deliciosas que convidan a sentir y a gozar.

A las retretas mencionadas, que actualmente tienen lugar los lunes, miércoles y viernes, acude más público que los demás días, contándose bastaste señoras y señoritas que de otro modo no concurrirían al paseo, ni buscarían el fresco y el esparcimiento en beneficio de su salud, pues la mujer habanera está imbuida de rancias preocupaciones y cree que su concurso solo es natural cuando algún atractivo lo justifica. De esta como de otras ideas extravagantes son culpa la monotonía y falta de aliento que encuentra el hombre en todas partes, casi desiertos como los lugares públicos se ven por el sexo femenino, que es al que le toca embellecer la vida no solo con su presencia y sus galas sino con su contento. No es empero grande el número de personas de ambos sexos que concurren al Parque en las noches de retreta, exceptuando ciertas solemnidades, dada la población y siendo el único punto de esparcimiento de la ciudad, pues si bien parece lo contrario al que se sitúe en la parte que hace frente al teatro de Tacón, es, porque para mayor amaneramiento y falta de gracia, los paseantes no salen de ese corto tramo, apiñándose como si no hubiese más espacio. Todos andan graves y como pagados de su propia importancia; parece más que paseo una imposicion obligatoria que tienen las damas y los caballeros de codearse por el espacio de dos horas sin decirse oste ni agoste, y volverse a sus casas con tanto spleen como trajeron. Falta de las muchachas la naturalidad y el despejo que tanto realzan a las mujeres de las grandes ciudades y a los hombres el entusiasmo y la franqueza elegante de la juveatud europea.

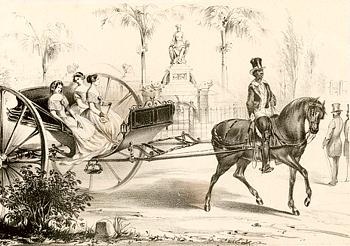

Las damas que tienen carruage no se apean y pretextan escuchar la música, formándose por esta causa una molesta aglomeración de vehículos por la parte exterior de aquel indispensable tramo. Cuando se sabe que estas sibaritas no ejercitan sino muy raras ocasiones las piernas no puede uno menos que exclamar: ¡qué fastidio! Los amigos se acercan a saludarlas y a endulzar los oídos de la pretendida, y es el único conato de sociedad que se forma en el Parque aunque poco propio en la forma, pues que quedan los caballeros obligados a permaneeer entre un maremagnum peligroso.

propio en la forma, pues que quedan los caballeros obligados a permaneeer entre un maremagnum peligroso.

Algunos grupos de hombres se forman sin erubargo, y aunque en dos o tres de estos que son habituales se notan personas instruidas que cultivan con su conversación asuntos elevados, la mayoría son de jóvenes que no llevan otro objeto aparente sino reírse de sus propios dicharachos, siempre faltos de gracia y oportunidad y que molestan los oidos del hombre juicioso, dando pobrísima idea del estado mental de una generación que tiene elementos sobrados de perfeccionamientos. Con semejantes galanes, cómo han de brillar las mujeres!

Todo el rededor del Parque está poblado de vistosos edificios, alguno paralizada su construcción por causas imprevistas, yen el lado en que está el teatro de Tacón, de fama universal, están muy buenos cafés, restauranes y hoteles, resplandecientes de luz y de animación, mereciendo el café el Louvre por su fisonomía que le dediquemos uno de nuestros capítulos así como a la bulliciosa acera que toma su nombre y que se extiende hasta la calle de Neptuno.

Sigue después el paseo del Prado que nos lleva hasta el mar y que nada particular ofrece de mención a no ser su constante brisa y marítimo panorama. En este trayecto están el magnífico establecimiento hidrotepiraco de Belot, el Centro de Dependientes, sociedad de instrucción y recreo y el Círculo Militar, elegante casino de los hijos de Marte, con muchas comodidades yque como de reciente creación no se sabe aún de qué pié cojea.

Quiero dejar un testimonio de mi cariño por la ciudad que perdure más que ella misma, para que siempre podamos volver aunque sea por los caminos del espacio cibernético. Yo adivino el parpadeo de las luces que a lo lejos, van marcando mi retorno… Y volver, volver, volver…

El hijo del Cerro, Caracas

Sigamos visitando este árbol espléndido que es solo una imagen fija, que no está en ninguna parte, para que sea de todos. Gracias a La Habana Elegante por mantener vivo el milagro de una ciudad que parece nacer de nuevo con cada entrega del Templete. Ojalá pronto podamos ser libres todos los cubanos y entrar y salir de la ciudad, no como extranjeros, ni como enemigos. Besos para todos.

Julia Jiménez, Orlando

Nocturno con fondo lunar

Juan Carlos Flores

Li Tai Po miraba la luna.

Por la época en que Li Tai Po miraba la luna

era un hombre muy descreído, muy solo.

Siendo expulsado del palacio por el emperador

andaba bucólico y nostálgico de montaña en montaña.

Li Tai Po miraba a la luna.

Cerraba los ojos y se iba quedando dormido.

El Louvre

Es un hermoso café que está situado en la esquina donde comienza la calle de San Rafael y que sirve de punto de reunión a la gente de mundo que habita, ya como estable, ya como transitoria, esta ciudad. Salones espaciosos y ventilados, cubiertas sus paredes y columnas de espejos y brillantemente alumbrados, ofrece un lugar

elegante y céntrico a la multitud de empleados, militares, marinos, negociantes, etc., que carecen aquí de familia y que forman tertulias en las mesas del establecimiento, muy bien servido y provisto de cuanto puede antojársele al paladar más exigente. El bullicio que produce la incesante charla de los concurrentes, da un carácter de

fiesta atractiva, y puede decirse que si se cerrase el Louvre sería un día de duelo para los que saben saborear la vida, pues difícilmente se encontraría otro lugar en la ciudad que supliese al que vamos describiendo.

Es un hermoso café que está situado en la esquina donde comienza la calle de San Rafael y que sirve de punto de reunión a la gente de mundo que habita, ya como estable, ya como transitoria, esta ciudad. Salones espaciosos y ventilados, cubiertas sus paredes y columnas de espejos y brillantemente alumbrados, ofrece un lugar

elegante y céntrico a la multitud de empleados, militares, marinos, negociantes, etc., que carecen aquí de familia y que forman tertulias en las mesas del establecimiento, muy bien servido y provisto de cuanto puede antojársele al paladar más exigente. El bullicio que produce la incesante charla de los concurrentes, da un carácter de

fiesta atractiva, y puede decirse que si se cerrase el Louvre sería un día de duelo para los que saben saborear la vida, pues difícilmente se encontraría otro lugar en la ciudad que supliese al que vamos describiendo.

Multitud de personas de distintas categorías sociales acuden allí en pos de citas, ytambién tahures y toda clase de gente vividora o alegre que se conciertan para sus aventuras. Es el verdadero círculo de la gente despreocupada y traviesa de levita, que fragua planes de conquistas femeniles, de burlas a la policía, y de toda clase de negocios nonc santos. Los que son prácticos clasifican prontamente la calidad de los distintos grupos que por zonas toman posesión de las mesas del café a diferentes horas, y con una sola mirada pueden decir cómo anda el barómetro de la moralidad pública. En los altos hay juegos de billar y tresillo y algunas veces se dan bailes donde alternan las razas sin las preocupaciones que en otras esferas, bailando muchos jóvenes que se tienen por paletos y elegantes, con lavanderas y fregonas de color de ébano que huelen a sebo y a cebolla y que fingen ocultar su rostro con la careta, que es de todas épocas en esta clase de bailes.

que fingen ocultar su rostro con la careta, que es de todas épocas en esta clase de bailes.

Pero dejemos el interior del Louvre que bajo su brillante aspecto tiene muchas telarañas y a las que echaremos un velo por no disgustar a las muchas personas intachables que allá concurren, y plantémonos en la acera que da frente al Parque y que es el lugar más animado y turbulento de la Habana y reflejo de nuestro carácter, que allí se ostenta con mayor espansión por estar al aire libre.

Es una semejanza aunque en menor escala de la Puerta del Sol de Madrid y un lugar verdaderamente alegre. Todo lo que no cabe dentro del café está, en la acera. Billeteros de todas las loterías nacionales, que gritan desaforadamente su mercancía; vendedores de periódicos y debastones, limpiabotas, limosneros, convidadores de garitos, truhanes de todas especies, jugadores, agentes o corredores de la tienda de Cupido; policía uniformada y secreta que todo lo husmea; vagos que esperan la llegada de algún amigo que los convide a cualquiera cosa, ycuantas clases de petardistas pueda imaginar el lector, se hallan allá en alegre roce con otras muchas gentes honradas que pasean por la anchurosa yelegante acera, gozosas de haber encontrado un lugar que contrasta por su belleza con la fealdad y estrechez del resto de la población. Allí se chismea todo lo que pasa ylo que no pasa; atraviesan las ninfas de ciertas calles para recordar su existencia ysus gracias a los disolutos, y también llegan en sus carruajes y a pie damas honestas yencopetadas a saborear los helados de París, que se confeccionan en un establecimiento especial.

Se discuten las reputaciones, se cena en los buenos restaurantes, se bebe, se gesticula y se riñe. Es la acera del Louvre como la caja de Pandora, donde están los males y los bienes. Allí está todo o por allí pasa todo lo fashionable de la Habana. No hay necesidad de ir a otro sitio para hallar lo que se desea, y lo mismo se puede encontrar una mirada de virgen tropical que regenere hasta á un escéptico, que otra que conduzca a una sentina de corrupción; y puede encontrarse también un carterista que le escamotee la cartera del bolsillo.

Se discuten las reputaciones, se cena en los buenos restaurantes, se bebe, se gesticula y se riñe. Es la acera del Louvre como la caja de Pandora, donde están los males y los bienes. Allí está todo o por allí pasa todo lo fashionable de la Habana. No hay necesidad de ir a otro sitio para hallar lo que se desea, y lo mismo se puede encontrar una mirada de virgen tropical que regenere hasta á un escéptico, que otra que conduzca a una sentina de corrupción; y puede encontrarse también un carterista que le escamotee la cartera del bolsillo.

Los demás establecimientos de la acera son a cual mejores y se clasifican así:

Hotel yrestaurant de Inglaterra, el primero que se montó con lujo en esta ciudad y cuyo salón de comer se ve siempre muy concurrido.

Cosmopolitan, café y restaurant, donde se come muy bien y sobre todo, se cena.

Washington, café y también restaurant, muy decente.

Casino alemán, círculo privado, en los altos.

Helados de París.

Barbería el Louvre, acicalamiento de jóvenes a la moda.

Hotel y restaurant Hispano Americano, más modesto.

Como se ve y contando con los alrededores, puede vivirse muy confortablemente sin salir de este centro, que no tiene que envidiar mucho a los de otras capitales.

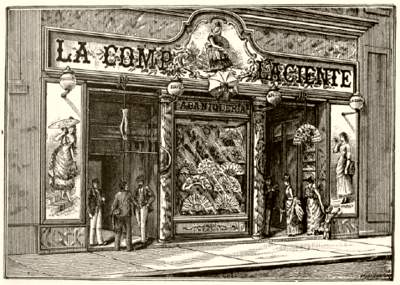

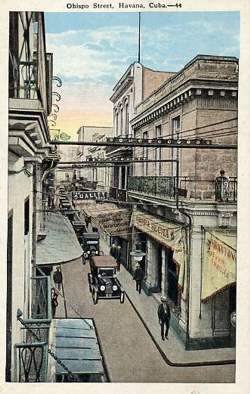

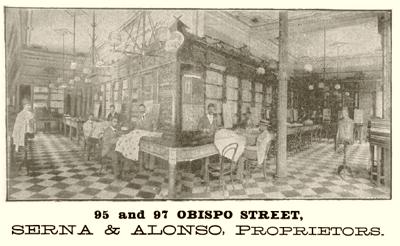

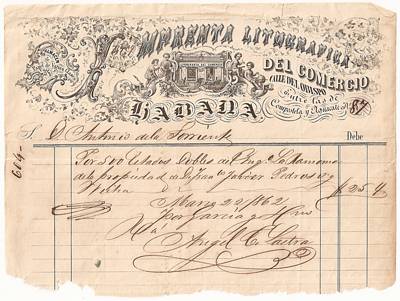

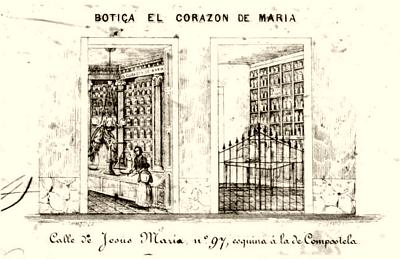

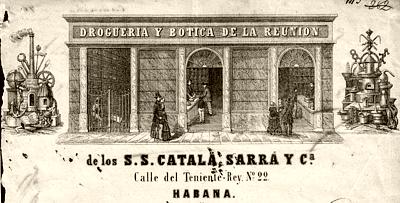

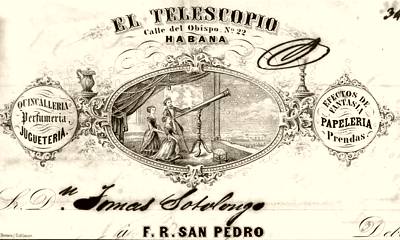

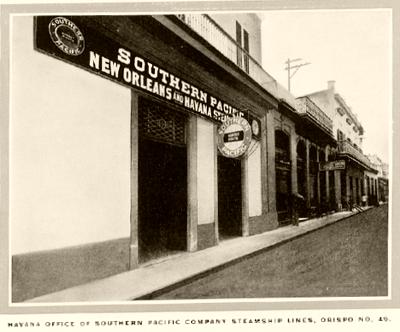

La Calle del Obispo

Comercial pasadizo entre la Plaza de armas y el Parque Central vamos a transitar, mirando a un lado y a otro los atractivos de la moda, las joyas relucientes, las porcelanas seductoras, las galas todas del trabajo y la inteligencia europea que se ostentan con profusión en la Habana. Un continuo cordón de carruajes en muchos de los cuales se muellen las damas más elegantes, se detienen aquí y allá, al frente de tiendas de todas clases, haciendo provisión sus dueñas de los efectos neeesarios para distinguirse en una sociedad cada día más exigente, que renueva a cada instante sus trajes, sus ajuares y hasta el modo de decir y saludar. Las leyes de la evolución y

Comercial pasadizo entre la Plaza de armas y el Parque Central vamos a transitar, mirando a un lado y a otro los atractivos de la moda, las joyas relucientes, las porcelanas seductoras, las galas todas del trabajo y la inteligencia europea que se ostentan con profusión en la Habana. Un continuo cordón de carruajes en muchos de los cuales se muellen las damas más elegantes, se detienen aquí y allá, al frente de tiendas de todas clases, haciendo provisión sus dueñas de los efectos neeesarios para distinguirse en una sociedad cada día más exigente, que renueva a cada instante sus trajes, sus ajuares y hasta el modo de decir y saludar. Las leyes de la evolución y  transformismo que ahora han acogido los filósofos con inusitada sorpresa, la descubrieron de nuevo mucho antes las mujeres con el auxilio de los catálogos de tiendas y periódicos de modas, que aparecen en las casas de familia allá por los rinconcitos donde no miran nunca los hombres, cuando tanta influencia ejercen estos impresos en el porvenir. Se devanan luego los secos ministros y legisladores poniendo cortapizas a las ideas que se desarrollan en periódicos y libros políticos, creyendo contener al espíritu humano, por el temor oculto aunque disfrazado, de que lleguen nuevas falanges a quitarles el puesto en el festín social y empobrecerlos, y no ven, miopes, que dentro de casa tienen la vorágine que los arrastra con mujer, hijos y criados, al campo revolucionario, donde por el poder de la industria y de la moda se confunden las clases sociales todas, vestidas de igual manera y en el que quedan vencedores los más audaces, mientras ellos cegados por el polvo, quedan sepultados en el abismo.

transformismo que ahora han acogido los filósofos con inusitada sorpresa, la descubrieron de nuevo mucho antes las mujeres con el auxilio de los catálogos de tiendas y periódicos de modas, que aparecen en las casas de familia allá por los rinconcitos donde no miran nunca los hombres, cuando tanta influencia ejercen estos impresos en el porvenir. Se devanan luego los secos ministros y legisladores poniendo cortapizas a las ideas que se desarrollan en periódicos y libros políticos, creyendo contener al espíritu humano, por el temor oculto aunque disfrazado, de que lleguen nuevas falanges a quitarles el puesto en el festín social y empobrecerlos, y no ven, miopes, que dentro de casa tienen la vorágine que los arrastra con mujer, hijos y criados, al campo revolucionario, donde por el poder de la industria y de la moda se confunden las clases sociales todas, vestidas de igual manera y en el que quedan vencedores los más audaces, mientras ellos cegados por el polvo, quedan sepultados en el abismo.

Y esta revolución tan demoledora ¿quién la hace? La hacen simplemente esos cuadernos sin autor o alguna escritora

Y esta revolución tan demoledora ¿quién la hace? La hacen simplemente esos cuadernos sin autor o alguna escritora parlanchina que cuenta en periodiquines de modas o folletines, faustos de princesas y duquesas, yla rematan después algunos industriales modestos, exponiendo en las vidrieras de las tiendas todo el oropel aristocrático a precios ínfimos. ¿Qué mujer no es ahora la Pompadour o la Valois, o princesa rusa, por ocho o diez pesos en billetes? Así es que cuando la costurera va echando chispas con gasas de algodón ydiamantes californianos, la dama aristocrática se despecha y traga bilis primero yluego se traga la fortuna del marido comprando diariamente efectos caros para no quedar eclipsada; y así viene a despecho de los conservadores y cruzando mares de bayonetas y cañones el nivel social tan temido, por medio de la química y el estampado y por la presunción del bello sexo que no mide otra cosa sino varas de encajes y telas bordadas, mientras el grave y sesudo marido anda confundido, no sabiendo explicarse en presurosa ruina y echando la culpa al patronato, a Voltaire, a Proudhone y a los nihilistas, sin acordarse para nada de los papeles de modas de su mujer y de las tiendas de novedades.

parlanchina que cuenta en periodiquines de modas o folletines, faustos de princesas y duquesas, yla rematan después algunos industriales modestos, exponiendo en las vidrieras de las tiendas todo el oropel aristocrático a precios ínfimos. ¿Qué mujer no es ahora la Pompadour o la Valois, o princesa rusa, por ocho o diez pesos en billetes? Así es que cuando la costurera va echando chispas con gasas de algodón ydiamantes californianos, la dama aristocrática se despecha y traga bilis primero yluego se traga la fortuna del marido comprando diariamente efectos caros para no quedar eclipsada; y así viene a despecho de los conservadores y cruzando mares de bayonetas y cañones el nivel social tan temido, por medio de la química y el estampado y por la presunción del bello sexo que no mide otra cosa sino varas de encajes y telas bordadas, mientras el grave y sesudo marido anda confundido, no sabiendo explicarse en presurosa ruina y echando la culpa al patronato, a Voltaire, a Proudhone y a los nihilistas, sin acordarse para nada de los papeles de modas de su mujer y de las tiendas de novedades.

Y no se alarmen los tenderos por estas revelaciones nuestras, pues por más que se patenticen no han de variar las cosas tal como las han puesto los tiempos, y el comercio ha de seguir cada día mas próspero, cumpliendo la humanidad con su destino.

La calle del Obispo representa el espíritu innovador de la época y no frece nada tradicional que considerar. Cuando han llegado épocas de crisis se la ha visto abatida, cerrando puertas ydisminuyendo artificios, y así que ha renacido la calma, aparecer de nuevo más diamante y convidadora al lujo, con firmas y rótulos nuevos. No hace aún mucho tiempo infundía terror en las almas timoratas el espectáculo que presentaba la calle, y éstas al pasar y

La calle del Obispo representa el espíritu innovador de la época y no frece nada tradicional que considerar. Cuando han llegado épocas de crisis se la ha visto abatida, cerrando puertas ydisminuyendo artificios, y así que ha renacido la calma, aparecer de nuevo más diamante y convidadora al lujo, con firmas y rótulos nuevos. No hace aún mucho tiempo infundía terror en las almas timoratas el espectáculo que presentaba la calle, y éstas al pasar y ver que cada día se despoblaba más, salían exclamando: “No hay esperanzas, la isla de Cuba está hundida!” Descorazonaba efectivamente mirar desaparecer el simpático comercio de la más céntrica vía, y parecían sus heridas las de todo el mundo. Hoy ha renacido como el ave Fénix con mayor esplendor y atractivo y también ha dado confianza a los tristes pesimistas que a cada rato se figuran con la maleta en la mano, en busca del alimento que creen les ha de faltar en la tierra de los plátanos y los ñames.

ver que cada día se despoblaba más, salían exclamando: “No hay esperanzas, la isla de Cuba está hundida!” Descorazonaba efectivamente mirar desaparecer el simpático comercio de la más céntrica vía, y parecían sus heridas las de todo el mundo. Hoy ha renacido como el ave Fénix con mayor esplendor y atractivo y también ha dado confianza a los tristes pesimistas que a cada rato se figuran con la maleta en la mano, en busca del alimento que creen les ha de faltar en la tierra de los plátanos y los ñames.

Y muy risueña y muy bonita está la calle del Obispo. Así que se comienza a andar se tropieza con un rico almacén de pianos, instrumento que en manos de la mujer anima tanto las ciudades cultas, porque siempre saben sacar de ellos en dulces armonías una  parte de sus almas sensibles; pertenece el establecimiento a los señores Esperez y hermano. Vienen después por sucesión infinidad de establecimientos vistosos que iremos nombrando sin detenernos mucho en ellos porque no parezcan interesadas estas citas. El Valle del Yumurí, lindísima tienda de fantasías parisiens, instalado con gusto exquisito; depósito elegante de máquinas de coser de Singer donde además hay mil efectos útiles de la industria americana; La Fashionable, linda tienda de modistas donde se ven a menudo fastuosos trajes de recepción y de baile; la magnífica joyería y relojeria El Bon Marché, del apreciable Sr. Enrique Schoechlin, que ha agradecido a la ciudad su fortuna dotándola con tan elegante tienda, que se distingue por los costosos kioscos traídos de Europa. Merece un aplauso este caballero suizo y no se lo escatimamos. Platería La Marina; La Joven América, locería; café y dulcería La Abeja Montañesa; Ciudad de Londres, sastrería; las tiendas de sedería y ropas que llevan el nombre de Correo de París; la sombrerería del popular Celestino Alvarez; Kramer, relojería; La Reina de las Flores, soberbia peluquería francesa digna de la capital de la elegancia y que justifica su poético rótulo; el Bosque de Bolonia, también fascinador por sus artículos y buen gusto parisiense; La Dalia Azul,

parte de sus almas sensibles; pertenece el establecimiento a los señores Esperez y hermano. Vienen después por sucesión infinidad de establecimientos vistosos que iremos nombrando sin detenernos mucho en ellos porque no parezcan interesadas estas citas. El Valle del Yumurí, lindísima tienda de fantasías parisiens, instalado con gusto exquisito; depósito elegante de máquinas de coser de Singer donde además hay mil efectos útiles de la industria americana; La Fashionable, linda tienda de modistas donde se ven a menudo fastuosos trajes de recepción y de baile; la magnífica joyería y relojeria El Bon Marché, del apreciable Sr. Enrique Schoechlin, que ha agradecido a la ciudad su fortuna dotándola con tan elegante tienda, que se distingue por los costosos kioscos traídos de Europa. Merece un aplauso este caballero suizo y no se lo escatimamos. Platería La Marina; La Joven América, locería; café y dulcería La Abeja Montañesa; Ciudad de Londres, sastrería; las tiendas de sedería y ropas que llevan el nombre de Correo de París; la sombrerería del popular Celestino Alvarez; Kramer, relojería; La Reina de las Flores, soberbia peluquería francesa digna de la capital de la elegancia y que justifica su poético rótulo; el Bosque de Bolonia, también fascinador por sus artículos y buen gusto parisiense; La Dalia Azul, tienda de ropas; La Francia, verdadero centro de la revolución, donde se ofrecen las

tienda de ropas; La Francia, verdadero centro de la revolución, donde se ofrecen las  telas más vistosas al alcance de todo el mundo; Botica de La Luz; sastrería de Aranguren; Inglaterra, otra tienda de ropas de empuje; El modelo, id; La Discusión, sastrería; La Germanía, sombrerería; plantas y semillas de A. D. Predegal; El Jardín, florería; Imprenta Central, de dos apreciables jóvenes; librería de Villa, que sube como la espuma yprotege las letras cubanas; La Gran Señora, peletería; Cuesta y comp., platería; Gronzález y Gonzálex, ópticos; S. B. Haase, antiguo y reputado bazar de objetos de arte, prendería y óptica; biscochería de París; La Bota de París, zapatería; Las Filipinas, conocida tienda de ropas; Perfumería Habanera; La Sociedad, sastrería económica; librería de Elías Fernández; La Galería Literaria, libros y periódicos ilustrados de Madrid; El Mallorquin, café y chocolate; Europa, grande y concurrido café y dulcería, etc.; La Imperial, peletería; El Paseo, id.; J. Navalon, sastrería elegante; Botica de Basset; El Modelo Cubano, chocolatería y armas; La Diana, gran tienda de ropas; El anteojo, quíncallería; La Granada, tienda de ropas; galletería y comestibles de Santo Domingo, muy renombrada; La Hispano Cubana, sombrerería; La Mariposa, locería; La Dominica, peletería; La Australia, perfumería; Botica de Santo Domingo.

telas más vistosas al alcance de todo el mundo; Botica de La Luz; sastrería de Aranguren; Inglaterra, otra tienda de ropas de empuje; El modelo, id; La Discusión, sastrería; La Germanía, sombrerería; plantas y semillas de A. D. Predegal; El Jardín, florería; Imprenta Central, de dos apreciables jóvenes; librería de Villa, que sube como la espuma yprotege las letras cubanas; La Gran Señora, peletería; Cuesta y comp., platería; Gronzález y Gonzálex, ópticos; S. B. Haase, antiguo y reputado bazar de objetos de arte, prendería y óptica; biscochería de París; La Bota de París, zapatería; Las Filipinas, conocida tienda de ropas; Perfumería Habanera; La Sociedad, sastrería económica; librería de Elías Fernández; La Galería Literaria, libros y periódicos ilustrados de Madrid; El Mallorquin, café y chocolate; Europa, grande y concurrido café y dulcería, etc.; La Imperial, peletería; El Paseo, id.; J. Navalon, sastrería elegante; Botica de Basset; El Modelo Cubano, chocolatería y armas; La Diana, gran tienda de ropas; El anteojo, quíncallería; La Granada, tienda de ropas; galletería y comestibles de Santo Domingo, muy renombrada; La Hispano Cubana, sombrerería; La Mariposa, locería; La Dominica, peletería; La Australia, perfumería; Botica de Santo Domingo.

Aquí llegamos a la esquina de la calle de Mercaderes, y aunque sigue la del Obispo hasta el muelle, cambia la decoración por entrar en el centro del Gobierno y de los agiotistas de bolsa y tener nuestra pluma que hacer nuevos enristres. Los establecimientos de la línea que hemos recorrido suman ciento cuarenta yocho. Todas las industrias ybellas artes están honoríficamente representadas y el público mira con particular cariño a la calle del Obispo que es un buen representante de la civilización del siglo XIX.

Hace cuarenta años que no veo La Habana. He vivido en París, en Madrid y en San Juan. Pero La Habana se ha convertido en una ciudad lejana, a la que solo puedo entrar por mis recuerdos. Es una ciudad extraña y la extraño. Por eso entrar a este Templete es para mí tan importante. Gracias por hacer posible mi regreso cada año.

El huésped del Hotel Pasaje

La Calle de San Rafael

Otro semi-boolevar se nos presenta por el que conducir anuestros lectores, pues basta ahora hemos huido de meternos en calles faltas de atractivos, temerosos de fastidiar con la charla de los defectos de nuestras costumbres. Quizá mas adelante diremos alguna cosa. Ya

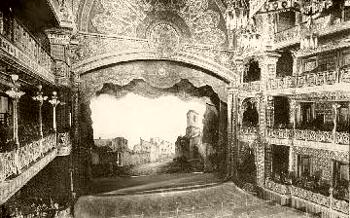

hemos hablado del famoso Louvre; frente tenemos un costado del gran teatro de Tacón, imponente edificio por sus dimensiones. Un catalan hijo del pueblo, y de escasa instrucción llevó a cabo esta obra en una época en que la Habana era respecto al presente, casi una aldea, y es la diferencia que siempre encontramos entre los hombres y

gobiernos pasados y los presentes, cuando nos ponemos a examinar las cosas. Tomaremos de una reciente publicación algunos datos sobre lo que representa ese teatro:

Otro semi-boolevar se nos presenta por el que conducir anuestros lectores, pues basta ahora hemos huido de meternos en calles faltas de atractivos, temerosos de fastidiar con la charla de los defectos de nuestras costumbres. Quizá mas adelante diremos alguna cosa. Ya

hemos hablado del famoso Louvre; frente tenemos un costado del gran teatro de Tacón, imponente edificio por sus dimensiones. Un catalan hijo del pueblo, y de escasa instrucción llevó a cabo esta obra en una época en que la Habana era respecto al presente, casi una aldea, y es la diferencia que siempre encontramos entre los hombres y

gobiernos pasados y los presentes, cuando nos ponemos a examinar las cosas. Tomaremos de una reciente publicación algunos datos sobre lo que representa ese teatro:

“El teatro de Tacón acupa una superficie de 6176 varas cuadradas; tiene por el frente tres puertas, seis por la calle de San Rafael, tres por la del Consulado y dos que dan a la de San José. En la esquina que forman las calles del Prado y San Rafael, está el café llamado Salon Brunet.

“Fijándonos en la parte interior del teatro, veremos que la platea y el escenario miden una extensión de 42.83 metros de largo, por [¿2?]0.68 de ancho, y la embocadura 17. 36. Las localidades pueden repartirse del modo siguiente: 56 palcos de 1.º y 2.º piso, 8 id del 3.º, 6 grillés, 112 butacas de tercer piso, 552 lunetas, 101 sillones delanteros de tertulia, 500 asientos de tertulia, 103 sillones delanteros de paraíso, 500 asientos de idem. Este número de asientos da cabida a 2,287 espectadores, que sumados con 750 más que pueden colocarse de pie detrás de los palcos, hacen 8000 personas que pueden asistir a una función. El alumbrado consta de 1,034 quemadores de gas; el decorado se compone de 751 telones, bastidores, bambalinas, etc.; la sala de armas posee 605 piezas de diferentes clases; el guardarropa 13,787 trajes; los muebles y útiles de la escena llegan a 782; el archivo contiene mas de 1,200 libretos de obras líricas ydramáticas....”

Mas no te entusiasmes demasiado, lector, con las grandezas anotadas, porque ya casi todo el decorado está en ruinas y los trajes hechos visiones. No ha tenido reemplazo el que creó esas maravillas.

los trajes hechos visiones. No ha tenido reemplazo el que creó esas maravillas.

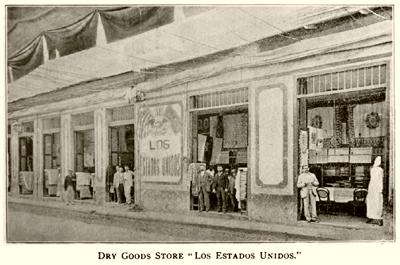

Después, hasta llegar a la calzada de Galeano, siguen una doble fila de establecimientos, que hasta la mitad de la calle indican el dominio del sexo bigotudo. Restauranes, barberías, sombrererías, sastrerías y zapaterías incitan a elegantizarse al más despreocupado, y la animación que producen los indispensables carruages, hacen de la calle de San Rafael un lugar favorito. Es también sitio preferente de las quincallerías, que se aumentan, llamando la atención con sus múltiples y vistosos objetos. Iremos indicando los establecimientos, según los vamos encontrando, sorprendidos siempre por el número de los que cuenta la Habana.

El Refrigerador Central, que recuerda los Lunch Rooms de Nueva York. Ha popularizado el uso del lager bieer de los alemanes, con tan buen éxito, que cuesta trabajo por las noches conseguir puesto para empinar el codo. La Granja, favorito café de los que prefieren un buen artículo a lucir el taco; Las Tullerías, antiguo restaurant de placentera historia; el Louvre, restaurant, tan bueno para comer como para probar que se come. En los altos se le rinde culto constante a Tersípcore por gente de todos colores y triviales y disolutas costumbres. Sombrerería El Louvre; Eliseo Badía, sastre; Locería y Cristalería; Cervantes, café y billar; Los Tiroleses, quincallería famosa; Fernandez Canto y comp., almacén de víveres digno de ser recomendado; Valles, sastre popular que imita a Nicolls el de  Nueva York en lo de anunciarse y complacer; confitería,que por llamarse de Lourdes, indica milagros; barbería y peluquería El Oriente; el famoso Néctar Soda, favorito de las damas; Los Puritanos, qaincallería; sombrerería de Morell; id. de Cándido Junquera; Naranjo, zapatería; A. T. Rodríguez, sastre; Mazas y comp., sombrerería; Los Bohemios, sastrería; Agustín Alvarez, fábrica de sombreros; Ropa Hecha. Estamos en la esquina de la calle de la Amistad donde nos detendremos delante de la casa escuela gratuita de la institución Zapata, para rendir homenage a un benemérito ciudadano que legó un capital para la instrucción pública. Pocas veces encontraremos entre nosotros tan bello ejemplo.

Nueva York en lo de anunciarse y complacer; confitería,que por llamarse de Lourdes, indica milagros; barbería y peluquería El Oriente; el famoso Néctar Soda, favorito de las damas; Los Puritanos, qaincallería; sombrerería de Morell; id. de Cándido Junquera; Naranjo, zapatería; A. T. Rodríguez, sastre; Mazas y comp., sombrerería; Los Bohemios, sastrería; Agustín Alvarez, fábrica de sombreros; Ropa Hecha. Estamos en la esquina de la calle de la Amistad donde nos detendremos delante de la casa escuela gratuita de la institución Zapata, para rendir homenage a un benemérito ciudadano que legó un capital para la instrucción pública. Pocas veces encontraremos entre nosotros tan bello ejemplo.

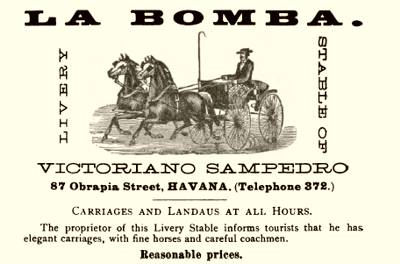

En el tramo siguiente varía la fisonomía de la calle, por las grandes tiendas de géneros que dan el dominio al sexo bello. Templo de Diana, quincallerfa; botica Cosmopolitana del Dr. Pormel; sedería La Diana; Arcaño, sastre; Las Tullerías, camisería; La Central, vidriería y grabados: Domingo Palli, zapatero; Taller de instalaciones de gas y agua; ferretería La Florida; ferreterfa de San Rafael; La Quinta Avenida, gran quincallería y emporio de novedades; Club Almendares, vistosa tienda de ropas; café El Nuevo Mundo; El Bazar, peletería; El Louvre, tren de coches de alquiler; La Traviata, tienda de ropas: sedería del Bazar Parisien; La Especialidad, camisería; lindo depósito de la fábrica habanera de perfomería de Crueellas, cayos productos son muy recomendables y merecen protección; El Bazar Parisien, famosa tienda de ropas; Los Estados Unidos, otra tienda de ropas como La Francia de la calle del Obispo; La Moda, peletería.

Aquí terminamos, porque la calle en vez de mejorar su anchura, sigue estrecha y triste. Doblaremos por Galeano, que es la vía mas típica de la Habana y una de las pocas que ofrece comodidades al pedreste.

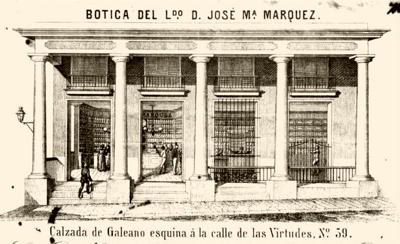

La Calzada de Galiano

Pasemos a otras sensaciones. Vamos saliendo de los barrios que nos recuerdan a Tiro por lo comercial, y entramos en una calle que bajo otro aspecto nos recuerda tambien a esas ciudades prehistóricas de las que quedan solo restos. Persépolis, Nínive, Babilonia, etc., vienen involuntariamente a la memoria al contemplar las largas filas de macizas columnas, sin gracia arquitectónica y que dio carácter tan monumental y pesado a construcciones de una época en que todo es lijero y artístico y en que la industria del hierro facilita al arquitecto los medios de lucírsela con poco costo, brindándole en delgado paral la resistencia de una pirámide. Mas a pesar de este defecto, sorprende agradablemente la calzada de Galiano al salirse de las estrechísimas y malsanas calles que componen casi toda esta poblacion, por la novedad que ofrece y porque nos hallamos en un centro social que nos empieza a apartar de los negocios y materialismos de la vida.

Pasemos a otras sensaciones. Vamos saliendo de los barrios que nos recuerdan a Tiro por lo comercial, y entramos en una calle que bajo otro aspecto nos recuerda tambien a esas ciudades prehistóricas de las que quedan solo restos. Persépolis, Nínive, Babilonia, etc., vienen involuntariamente a la memoria al contemplar las largas filas de macizas columnas, sin gracia arquitectónica y que dio carácter tan monumental y pesado a construcciones de una época en que todo es lijero y artístico y en que la industria del hierro facilita al arquitecto los medios de lucírsela con poco costo, brindándole en delgado paral la resistencia de una pirámide. Mas a pesar de este defecto, sorprende agradablemente la calzada de Galiano al salirse de las estrechísimas y malsanas calles que componen casi toda esta poblacion, por la novedad que ofrece y porque nos hallamos en un centro social que nos empieza a apartar de los negocios y materialismos de la vida.

Conócese ahora íntimamente a la Habana, y las familias vienen a recojer nuestra atención, ocupada con el populoso y  cosmopolita comercio que impera por todas partes. Vemos, sin embargo de que también le van robando sitio las tiendas a los particulares, que muchas de las casas están habitadas por familias, escuchándose tras los portales un bullicio simpático, y viéndose asomar las atractivas caras de la juventud y el entrar y salir en alegre retozo de los niños, produciendo este conjunto un cambio de ideas y de deseos.

cosmopolita comercio que impera por todas partes. Vemos, sin embargo de que también le van robando sitio las tiendas a los particulares, que muchas de las casas están habitadas por familias, escuchándose tras los portales un bullicio simpático, y viéndose asomar las atractivas caras de la juventud y el entrar y salir en alegre retozo de los niños, produciendo este conjunto un cambio de ideas y de deseos.

La sociedad cubana tiene todas sus glorias dentro de sus moradas; allí es espansiva, espléndida y generosa. Las mujeres, que tan mal se encuentran, como cohibidas en las vías públicas, están a sus anchas dentro de sus nidos y se muestran simpáticas y encantadoras. A veces parecen muy lánguidas, mas reservan para sus ojos toda la energía, y éstos dejan entrever un paraíso de dulzuras. ¿Dónde la mujer no reasume toda la vida y dónde no alienta é ilumina al hombre?

Sirve esta calle como de comienzo a dos barrios populosos: el de Monserrate y el de la Salud. El primero es el más favorito del sexo bello, y los Tenorios tienen allí largo campo donde ensayar sus aptitudes para atrapar simpatías y decisiones. No les intimide la displiecencia aparente de las muchachas, pues como se dice que ahora escasean los pretendientes, deben tener ellas una provisión de sies en la punta de la lengua, que con poco esfuerzo harán salir. El no es monosílabo poco simpático a las protectoras de la cascarilla.

Tiene la Habana, en medio de sus interminables defectos, algo original que seduce y hace que se perdonen aquellos. Tal atractivo empieza a experimentaree en la calle en que estamos; el gusano roedor del amor se introduce en nuestro pecho, y vamos como el cordero a la muerte, resignados, en busca de unos ojos, de una mirada que nos esclavicen. El amor es el imán de la humanidad; cuando estamos bajo su influencia todo cuanto nos rodea nos parece perfecto. Las columnas ridículas para el crítico, que dan aire de ruinas a la calzada de Galiano, toman formas vaporosas cuando en nuestra mente las miramos bajo el prisma de las simpatías, y sirven de peristilo a un templo de diosas, que pueblan extensos barrios, y son sencillas y amorosas y ardientes como el sol.

atractivo empieza a experimentaree en la calle en que estamos; el gusano roedor del amor se introduce en nuestro pecho, y vamos como el cordero a la muerte, resignados, en busca de unos ojos, de una mirada que nos esclavicen. El amor es el imán de la humanidad; cuando estamos bajo su influencia todo cuanto nos rodea nos parece perfecto. Las columnas ridículas para el crítico, que dan aire de ruinas a la calzada de Galiano, toman formas vaporosas cuando en nuestra mente las miramos bajo el prisma de las simpatías, y sirven de peristilo a un templo de diosas, que pueblan extensos barrios, y son sencillas y amorosas y ardientes como el sol.

Comienza la calzada en la de San Lázaro y termina en la de la Reina. Al llegar a la calle de la Concordia se encuentra la iglesia parroquial de Monserrate, única para un barrio de cuarenta mil habitantes y en la que apenas caben seiscientas personas. Esta insuficiencia marca la mudanza de los tiempos y de las ideas entre las dos épocas en que se fomentaron la parte antigua llamada in-tramuros y la moderna, ex-tramuros. La primera, edificada antes de la revolución filosófica, está poblada, al estilo de las ciudades peninsulares, de muchos templos costosos; en la parte de estos tiempos, una iglesita de aldea, sin ornato, sirve para cristianizar a una población como la que tendría la Habana antigua, y el clero no se inquieta por el pobre  servicio que presta a cambio de pingües beneficios. ¿Habrá invadido la filosofía también al clero?

servicio que presta a cambio de pingües beneficios. ¿Habrá invadido la filosofía también al clero?

Va a notar el lecter que entre el comercio que se va apoderando de la calzada y que vamas a reseñar, dominan las mueblerías: se han colocado como de atalaya para vigilar la creación de las familias y para hacerse también más visibles y animar a los solteros recalcitrantes. En todas estas indispensables tiendas hay muebles de segunda mano al alcance de la más inmodesta fortuna.