The Porous Dark, the Artificial Light

Al Schaller

My friendship with Edmundo has its origins on paper. I first became acquainted with him through his characters in Memorias del subdesarrollo: Malabre, the fragmented intellectual; Eddy, proud apologist for the revolution; Elena, vulnerable, capricious; even Emilio, whose unobtrusive generosity didn’t resonate till later.

Anxious to secure my translation rights, I scoured the Internet for his whereabouts. Cyberspace had him pegged as ‘enigmatic’ and ‘elusive,’ but I dug out an e-mail address, and he was delighted at my latest evidence that his work still resonated in this country. He was curious: Who are you, what’s your background, how did you come across my work? So I composed a careful reply. Silence. And another. Nothing. Suddenly I was Elena desperately pounding on his door. A stalker. I tried NYU where he had been teaching: he had no office, no phone, no forwarding address. His New York publisher would allow no trace of him.

Later when we began working together on our separate coasts and our correspondence grew, I found him to be warm and caustic, arrogant and self-effacing, morbid and funny, and a generous collaborator, not compulsively protective of his text. At first his comments were tentative, detached: “you might want to check the first 30 pages for mistakes.” Later he was more engaged and direct, though always restricting his comments to the outright error: “Line four should read ‘playing marbles’ not ‘rubbed dicks.’” Ouch. Did I mention he found it painful to go back over his work?

He has no use for agents, trusting in the power of his work to stand against the tyranny of the marketplace. He prefers to be invisible and let someone he trusts, however inexperienced, approach the brokers with his art. Who better to enlist than someone you scarcely know who doesn’t know a penis from a peewee? If his work rejects the forced feeding of products and ideas, how else then to insinuate his art without defrauding it, this poet of loss in a land of commercialized desire?

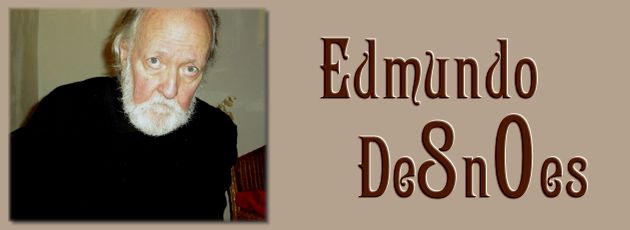

When we finally met, it was over lunch at his favorite Chinese-Cuban restaurant. He was in full dress uniform, although I didn’t know it at the time, black long-sleeved knit t-shirt, black slacks. Among his first questions to me was, “How did you find me?” I found him ‘elusive’ in terms of idle chatter, ‘enigmatic’ in my struggle to keep pace with his thought.

Later I caught up with the bone-marrow of his thinking: his ambition to bridge the deep cultural divide between the Spanish and the Anglo mind and tongue; his rejection of the hubris of both cultures that would try to capture and confine reality, the Spanish in an “asphyxiating embrace,” the Anglo inside a sterile shop window. If he admires Spanish passion and Anglo pragmatism, he decries the vanity of its delirium and its superficiality. Each culture could curb the other’s excesses with a healthy dose of doubt, “more productive than truth,” he writes. As his reclusive narrator ‘Edmundo” says in his latest novel, “The possession of failure is our only possible success.”

This ‘Edmundo’ of Memorias del desarrollo, this aging expatriate, warns his daughter, “I love you because I don’t want to possess you,” while he repeatedly tries to turn her away, knowing that his is a fragile detachment, this foolish, passionate man. Exiled from youth and love, from faith and truth, from the Pearl of the Antilles and the Big Apple, soon to be exiled from life itself, but never from thought and feeling, he aspires to retain his passionate intensity to the end and abandon life screaming like the autumn leaves, in a “fever of blood, a bellow of beauty.”

Like Willie in Happy Days (the Beckett play, not the TV show), Edmundo (the real one, not his narrator) has had one foot in the grave all the time I’ve known him, but he can still crawl out in top hat and tails when the occasion demands. This probably isn’t such an occasion. “Either every day is my birthday or I don’t want one,” he wrote me once.

Sorry, Edmundo. Are you there?

Happy 80th.