On Poetical Renovations in Alamar

Kristin Dykstra, Illinois State University

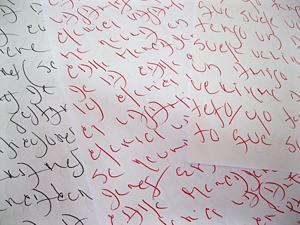

Juan Carlos Flores (b. Havana, 1962) composes his poems by hand, writing in a colorful, slanting script across sheets of paper. He admits that his handwriting is hard for most people to read. Fortunately its stylized leanings make complete sense to Mayra López, who types the work into a computer so that the poems can someday continue on to readers in a printed form. Along the way Flores revises his poems many times over, pursuing just the right equilibrium.

Juan Carlos Flores (b. Havana, 1962) composes his poems by hand, writing in a colorful, slanting script across sheets of paper. He admits that his handwriting is hard for most people to read. Fortunately its stylized leanings make complete sense to Mayra López, who types the work into a computer so that the poems can someday continue on to readers in a printed form. Along the way Flores revises his poems many times over, pursuing just the right equilibrium.

Flores is currently working on the third book in a trilogy to which he refers as his Poetical Resurrection of Alamar. Alamar, a housing community built just to the east of Havana in the late twentieth century, has been his home since 1971. He originally lived in Zone 4, one of the first sections to be built, and remembers a great deal of activity in the area – people, materials, a building completed in less than six months. Later he moved to Zone 6, where still he lives today.

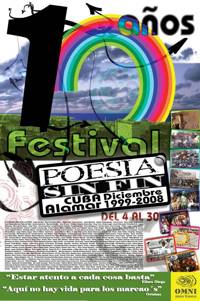

Flores has made a mark in Cuban culture both with written texts and performative experimentation. In 1990 he won the David Prize for his first book of poems, Los pájaros escritos. At the end of that decade, Flores founded Zona Franca, an alternative writer’s collective based in Alamar, with other poets. Their group went on to merge with a visual art group called OMNI. Together they became the dynamic, collaborative project now known as OMNI-Zona Franca (http://omnifestivalpoesiasinfin.blogspot.com/). Flores was its first director. The leadership and membership of the group have grown and changed over time, involving many other participants.

Flores went on to publish more collections of poetry. His collection Distintos Modos de Cavar un Túnel, the first book in his Alamar trilogy, won the 2002 Julián del Casal prize awarded by UNEAC. Editorial Torre de Letras in Havana has released small-press editions of his work, including a preview of the second book of the trilogy. That collection was subsequently picked up and published by Letras Cubanas in 2009 as El contragolpe (y otros poemas horizontales) – or in English, Counterpunch (and Other Horizontal Poems). The selections here are taken from that book.

In the remainder of my remarks preceding a set of translations, which appear below, I share a variety of details that emerged from my extended discussion with Flores about El contragolpe at his home in June 2010. My observations represent the working notes of a translator. These will overlap to some degree with the interests of criticism but will not advance according to a central scholarly thesis. My notes end with a brief speculation about a recurrent and suggestive structural feature of the poems, one that merits more sustained attention in the future. To the degree that there is an “argument” in my contribution as a whole, it is best embodied in the translations that follow these notes.

Flores told me that he envisions the explicitly “horizontal” prose poems as a site for challenging vertical – that is, hierarchical – aspects of society. Consulting him directly was important for working with his poems,

many of which register details of the history and culture of Alamar. Others range through the literary world of nearby Havana or examine phenomena characterizing the capital region in general. Tension regarding the recent construction of expensive tourist hotels, for example, runs through the poem “Hacky sack” (“Fuchi”).

sack” (“Fuchi”).

Documentary moments merge with dream, as in the example of “Amusement park” (“Parque de diversiones”). Here Flores refers to a real amusement park cobbled together in Alamar out of parts taken secondhand from other parks. At the same time he also specified that imagination plays an important role in this and other poems. A beggar imagines Alamar’s park; his vision paves the way before the place is physically built. A different, more ethereal iteration of the imaginary appears in “Number 10” (“El número 10”). The frustrated sports fan invents his own “order” based on the Lotus Sutra, with no counterpart in reality: imagination remains persistently other.

The lullabies and mother figure invoked in various selections here also play a role throughout Counterpunch. The adult world of Alamar – its history, pressing social issues written between the lines, the frustrations of people who turn to fantasy or alcohol for release – is consciously balanced off against language calling a child’s sphere to mind. Playfulness, a singsong style, and characters with colorful tales evoke a shelter in mythical innocence.

So do sport and recreation, for adults as well as children. I’ve chosen the translation “Counterpunch” rather than “Backlash” for the book’s title because Flores intends to reference boxing. Suggestively, a counterpunch doesn’t only respond to an opponent’s attack – it is an effort to exploit a new space, an opening created by the attack. In general his sporting references evoke allegory, or better said, chips of allegory that glint and wink at the reader before the tightly crafted poems foreclose further explanation. As exemplified in the soccer fan’s admissions in “Number 10,” these glimpses point us toward larger reflections about individuals and their relationships to community.

On a related note, “Hacky sack” does in fact refer to a literal hacky sack that a visitor once brought to Alamar, played with Flores and others, and left behind with them. When we discussed that poem, Flores demonstrated the game in his living room before presenting the hacky sack – now extremely used – to me ceremoniously. Like so many objects that arrive in the  Havana area from abroad, hacky sacks are not in the least “indigenous” or traditional in Cuba, and Flores is uncertain about how they came to be called “fuchi” in Alamar. And yet the object appeared, making its way into life and now his “poetical resurrection” of the community, testifying to connectivities.

Havana area from abroad, hacky sacks are not in the least “indigenous” or traditional in Cuba, and Flores is uncertain about how they came to be called “fuchi” in Alamar. And yet the object appeared, making its way into life and now his “poetical resurrection” of the community, testifying to connectivities.

More than any other feature a careful use of repetition, tempered by variation, characterizes the 2009 book. It is illustrated in all but one of the poems included here. Flores, who calibrates the rhythm of each poem with scrupulous attention, manipulates this technique with great versatility and a capacity to surprise. Sometimes his echoing phrases yield absurdity. Sometimes the effect leans more toward sadness, or tips into estrangement: at his best Flores creates a delicate feel of the uncanny, which calls out from its containment within a pressing, exaggerated sameness.

Why might this dynamic of sameness and its disruption have become so important in the structure of a poetical Alamar in Counterpunch?

Flores has arguably engaged the shape of his physical environment with this writing. He does not explicitly describe his poetics in these terms, so I offer my own reading now, influenced by working closely with the language of his book. Alamar’s construction resulted from an initiative of the 1970s to relieve housing pressures by erecting bedroom communities outside Havana. The authors of The History of Havana observe that the Eastern European design implemented for the neighborhood, “foreign to the architecture of Havana and to proposals developed by Cuban architects of the time—was repetitive and both functionally and esthetically not very good. Alamar [ . . .] became a sprawl of hundreds of nearly identical rectangular five-story concrete walkups spread out between a highway and the sea” (243).* I propose that the poet resurrects this architectural repetition, said to be “functionally and esthetically not very good,” by treating it as a springboard for creating something better.

Inside the repeating structures of his poetic landscapes, as in the five-floor walkups of Alamar, a tremendous energy resides. And that which is aging – be it this entire built community or, in the end, a single individual who has imagined and pursued a different way to live – can be renewed through poetry.

Sources

Cluster, Dick, and Rafael Hernández. The History of Havana. NY: Palgrave MacMillan, 2006.

The most important source for this commentary was my extended personal conversation with Juan Carlos Flores and Mayra López at their home in Alamar, on June 10, 2010. This conversation also influenced numerous choices I made for my translations of the poems and allowed me to see elements of Flores’ writing process. Additionally, Flores and López permitted me to take photographs and film video of Flores reading poems, and they participated in follow-up discussions with me over email in June and July. I would like to thank them for all their time and care.

* * *

Manuscripts

Deciphering what’s written in the wind, it´s a difficult task, behind the metallic fence or curtain, smoke, those who didn’t risk the leap, they devoted themselves to neighborly chatter, about what was there and what was done behind the metallic fence or curtain, those who risked the leap, they came back quieted, as if they had contracted some illness that impeded their speech, behind the metallic fence or curtain, smoke, writing what’s encrypted in the wind, it’s a difficult task.

Deciphering what’s written in the wind, it´s a difficult task, behind the metallic fence or curtain, smoke, those who didn’t risk the leap, they devoted themselves to neighborly chatter, about what was there and what was done behind the metallic fence or curtain, those who risked the leap, they came back quieted, as if they had contracted some illness that impeded their speech, behind the metallic fence or curtain, smoke, writing what’s encrypted in the wind, it’s a difficult task.

Manuscritos

Descifrar lo que está escrito en el viento, es tarea difícil, detrás de la cerca o cortina metálica, humo, quienes no se aventuraban a saltar, se dedicaban a un parloteo de vecinos, sobre lo que había y se hacía detrás de la cerca o cortina metálica, quienes se aventuraban a saltar, regresaban callados, como si hubiesen contraído una enfermedad que les impidiese el habla, detrás de la cerca o cortina metálica, humo, escribir lo que está cifrado en el viento, es tarea difícil.

A very fine fish

Fernando Pessoa enjoyed smoking black tobacco from the Antilles, and black tobacco from the Antilles leaves expressionist stains on your teeth (the life and death of the brilliant Portuguese are the life and death of a monk, or an aristocrat, without revenues, with one or two common pebbles in the elitist shoe). Fernando Pessoa enjoyed smoking black tobacco from the Antilles, and black tobacco from the Antilles leaves expressionist stains on your teeth (the poems of the brilliant Portuguese are the solitary poems of a monk, or an aristocrat, without revenues, with one or two common pebbles in the elitist shoe), because yes, because no, because between the yes and the no are all men located, Fernando Pessoa enjoyed smoking black tobacco from the Antilles, and black tobacco from the Antilles leaves expressionist stains on your teeth.

Fernando Pessoa enjoyed smoking black tobacco from the Antilles, and black tobacco from the Antilles leaves expressionist stains on your teeth (the life and death of the brilliant Portuguese are the life and death of a monk, or an aristocrat, without revenues, with one or two common pebbles in the elitist shoe). Fernando Pessoa enjoyed smoking black tobacco from the Antilles, and black tobacco from the Antilles leaves expressionist stains on your teeth (the poems of the brilliant Portuguese are the solitary poems of a monk, or an aristocrat, without revenues, with one or two common pebbles in the elitist shoe), because yes, because no, because between the yes and the no are all men located, Fernando Pessoa enjoyed smoking black tobacco from the Antilles, and black tobacco from the Antilles leaves expressionist stains on your teeth.

El castero

A Fernando Pessoa, le gustaba fumar el tabaco negro de Las Antillas, y el tabaco negro de Las Antillas deja manchas expresionistas en los dientes (la vida y la muerte del portugués genial son la vida y la muerte solitarias de un monje, o un aristócrata, sin rentas, con alguna que otra piedrecilla común, dentro del zapato elitista). A Fernando Pessoa, le gustaba fumar el tabaco negro de Las Antillas, y el tabaco negro de Las Antillas deja manchas expresionistas en los dientes (los poemas del portugués genial son los poemas solitarios de un monje, o un aristócrata, sin rentas, con alguna que otra piedrecilla común, dentro del zapato elitista), porque sí, porque no, porque entre el sí y el no están todos los hombres, a Fernando Pessoa, le gustaba fumar el tabaco negro de Las Antillas, y el tabaco negro de Las Antillas deja manchas expresionistas en los dientes.

Amusement park

The kids, if they get bored, break all the glass they find. The beggar, sprawled on newspapers, during the nights of Lent, face to the celestial store, dreams up the park. Now with aging apparatus, parts extracted from another park, they’re building the park. If I get bored, I break all the glass I find, I need a park.

face to the celestial store, dreams up the park. Now with aging apparatus, parts extracted from another park, they’re building the park. If I get bored, I break all the glass I find, I need a park.

Parque de diversiones

Los niños, si se aburren, rompen cuanto cristal encuentran. El mendigo, sobre periódicos echado, en noches de cuaresma, cara hacia bodega celeste, soñó el parque. Ahora, con aparatos viejos, extraídos de otro parque, están construyendo el parque. Si me aburro, rompo cuanto cristal encuentro, yo necesito un parque.

Number 10

Roberto Baggio is in front of the goalie, if he puts the ball in the net, his Team Italy will be able to win the coveted, the golden cup, I, a thousand and one shadows rhythmically burning, at last I put my things in order, within the order of the Lotus Sutra, I know what it means to belong to a soccer team, I know what it means to nail it and what it means to miss, art or soccer or war, working for something wears you out, working for nothing wears you out more. Roberto Baggio is in front of the goalie, if he puts the ball in the net, his Team Italy will be able to win the coveted, the golden cup, but Roberto Baggio misses, I, a thousand and one shadows rhythmically burning, at last I put my things in order, within the order of the Lotus Sutra, I know what it means to belong to a soccer team, I know what it means to nail it and what it means to miss, art or soccer or war, working for something wears you out, working for nothing wears you out more: those lullabies, mother, those lullabies, sing one for me.

Roberto Baggio is in front of the goalie, if he puts the ball in the net, his Team Italy will be able to win the coveted, the golden cup, I, a thousand and one shadows rhythmically burning, at last I put my things in order, within the order of the Lotus Sutra, I know what it means to belong to a soccer team, I know what it means to nail it and what it means to miss, art or soccer or war, working for something wears you out, working for nothing wears you out more. Roberto Baggio is in front of the goalie, if he puts the ball in the net, his Team Italy will be able to win the coveted, the golden cup, but Roberto Baggio misses, I, a thousand and one shadows rhythmically burning, at last I put my things in order, within the order of the Lotus Sutra, I know what it means to belong to a soccer team, I know what it means to nail it and what it means to miss, art or soccer or war, working for something wears you out, working for nothing wears you out more: those lullabies, mother, those lullabies, sing one for me.

El número 10

Roberto Baggio está frente al portero, si inserta el balón en la red, su equipo Italia podrá ganar la codiciada, la áurea copa, yo, una y mil sombras acompasadamente ardiendo, que finalmente me ordené, en orden del Sutra del Loto, sé lo que significa pertenecer a un equipo de fútbol, sé lo que significa acertar y sé lo que significa fallar, arte o fútbol o guerra, trabajar por algo cansa, trabajar por nada cansa más. Roberto Baggio está frente al portero, si inserta el balón en la red, su equipo Italia podrá ganar la codiciada, la áurea copa, pero Roberto Baggio falla, yo, una y mil sombras acompasadamente ardiendo, que finalmente me ordené, en orden del Sutra del Loto, sé lo que significa pertenecer a un equipo de fútbol, sé lo que significa acertar y sé lo que significa fallar, arte o fútbol o guerra, trabajar por algo cansa, trabajar por nada cansa más: aquellas nanas, mi madre, aquellas nanas, cántame una.

The kiss

Long is the night and at dawn’s crimson gates I say to myself: if I had a guitar between my hands, I wouldn’t be Silvio Rodríguez, or Chico Buarque, or Bob Dylan, or Bob Marley. Not ballad, or zamba, or blues, or reggae. Not Cuba, or Brazil, or the US, or Jamaica. I would be a remote and anonymous man, from a remote and anonymous place, singing a remote and anonymous song. Mother, I need you, mother, I love you, I don’t think I’ll ever learn how to lace my own shoes.

or the US, or Jamaica. I would be a remote and anonymous man, from a remote and anonymous place, singing a remote and anonymous song. Mother, I need you, mother, I love you, I don’t think I’ll ever learn how to lace my own shoes.

El beso

Larga la noche y frente a las puertas rojas del amanecer me digo: si yo tuviera entre mis manos la guitarra, no sería: Silvio Rodríguez, ni Chico Buarque, ni Bob Dylan, ni Bob Marley. Ni trova, ni zamba, ni blues, ni reggae. Ni Cuba, ni Brasil, ni Estados Unidos, ni Jamaica. Sería un hombre anónimo y remoto, de un lugar anónimo y remoto, cantando una canción anónima y remota. Madre, te necesito, madre, te amo, creo que jamás podré aprender a acordonarme los zapatos.

Hacky sack

Cold is the morning, the reel of fog causes confusion of churches with bars. Hacky sack, simply keeping a ball up in the air, using the entire body, the ball smaller than a fist, made of string and seeds. Cold is the morning and the jacket, not so warm. Just hotels, I’ve constructed buildings in which no one, ever, has to live. Cold is the morning, the reel of fog causes confusion of churches with bars. The guy who felt the vain happiness of a woman or a laying hen, as he was laying bricks, looks today toward the golden circle, into which six players have moved, unintentionally, they’ve gone through the fence of thorns dividing the west from the east, the future from the past. Though the sun is up already, the morning is still cold and the jacket, not so warm. Comrade, isn’t there some bar open around here, where I can have a spot of rum?

Fuchi

Fría está la mañana, la película de niebla hace que se confundan iglesias y bares. Fuchi, simplemente, sostener, con todo el cuerpo, en el aire una pelota, más pequeña que un puño, hecha de hilo y semillas. Fría está la mañana y poco abriga el gabán. Sólo hoteles, he construido edificios en los que nadie, nunca ha de habitar. Fría está la mañana, la película de niebla  hace que se confundan iglesias y bares. Aquel que tuvo la vana alegría de mujer o gallina ponedora, mientras colocaba ladrillos, mira hoy hacia el círculo dorado donde se colocan los seis jugadores que, sin proponérselo, traspasaron la cerca de púas que divide al occidente, del oriente, al futuro, del pasado. Aunque el sol ya salió, fría está aún la mañana y poco abriga el gabán. Compañero, ¿no habrá por ahí un bar abierto, en el que pueda tomarme una poca de ron?

hace que se confundan iglesias y bares. Aquel que tuvo la vana alegría de mujer o gallina ponedora, mientras colocaba ladrillos, mira hoy hacia el círculo dorado donde se colocan los seis jugadores que, sin proponérselo, traspasaron la cerca de púas que divide al occidente, del oriente, al futuro, del pasado. Aunque el sol ya salió, fría está aún la mañana y poco abriga el gabán. Compañero, ¿no habrá por ahí un bar abierto, en el que pueda tomarme una poca de ron?

Floral therapy

Thomas, priest-poet, enamored up to his humerus of a Sufi girl, before his departure, this time without a pack, toward foundational village of the mind, in moonlit clearing where passing through lianas, watery light filters, bringing a chill to bodies, and motors.

Heteronymous perhaps, solitary and calm, mind churning, between Alamar and Cojímar, over iron bridge, tossing crumbs to the usual fish, as sardines leap, remembering Thomas.

Pedro Marqués, my friend, there’s a certain sadness about this whole thing: like when one contemplates Buddha, after introducing alcohol into the stomach.

Terapia floral

Tomás, sacerdote-poeta, enamorado hasta el húmero de muchacha sufí, antes de la partida, sin mochila esta vez, hacia aldea erigida, bajo claro de luna, donde, atravesando las lianas, filtra luz acuosa que los cuerpos, los motores enfría.

Heterónimo acaso, solitario y tranquilo, cabeza roturada, entre Alamar y Cojímar, sobre puente de hierro, arrojando migajas a los peces comunes, mientras saltan sardinas, recordando a Tomás.

Pedro Marqués, mi amigo, hay cierta tristeza en todo esto, como cuando uno piensa en Buda, después de haber introducido en estómago alcohol.

Kristin Dykstra’s translation of a 1998 book of poems by the Cuban writer Omar Pérez, Did You Hear about the Fighting Cat?, is forthcoming from Shearsman Books Ltd. (Exeter, UK) in late 2010. In 2009 she was the recipient of a 2009 Literary Arts Residency at the Banff Centre (Alberta, Canada) for her work on Breach of Trust, a poetry collection by Ángel Escobar. Her past work is featured in bilingual editions of books by Reina María Rodríguez and Omar Pérez, including Something of the Sacred (Factory School, 2007), Time’s Arrest (Factory School, 2005), and Violet Island and Other Poems (Green Integer, 2004, tr. with Nancy Gates Madsen).

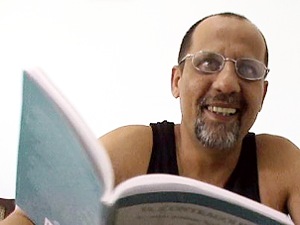

"Video still of Flores reading a poem at his home in Alamar. June 10, 2010. Filmed by Kristin Dykstra."