Diary of My trip to America and Havana

John Mark

Thursday, October 23RD.

On waking up at six this morning, we were entering the beautiful harbour at Havana, and made all haste to get a cup of coffee and be ready for landing. The grim-looking old fortress of the Morro Castle and Lighthouse on our left, and on the right were plainly visible the fort of La Punta, and the City. The houses appear to" be coloured white, blue, and yellow, with flat red-tiled roofs and without any chimneys. As soon as we dropped anchor, about a mile from the Custom House quay, a crowd of sailing-boats came alongside; the Government medical officer, and a lot of people to meet their friends, came on board, also quite a swarm of hotel-runners, who solicited our patronage very persistently, speaking both English and Spanish; at one time not less than eight or ten heads and hands with cards blocked my cabin door.

On waking up at six this morning, we were entering the beautiful harbour at Havana, and made all haste to get a cup of coffee and be ready for landing. The grim-looking old fortress of the Morro Castle and Lighthouse on our left, and on the right were plainly visible the fort of La Punta, and the City. The houses appear to" be coloured white, blue, and yellow, with flat red-tiled roofs and without any chimneys. As soon as we dropped anchor, about a mile from the Custom House quay, a crowd of sailing-boats came alongside; the Government medical officer, and a lot of people to meet their friends, came on board, also quite a swarm of hotel-runners, who solicited our patronage very persistently, speaking both English and Spanish; at one time not less than eight or ten heads and hands with cards blocked my cabin door.

A friend had bespoken rooms for us at the Hotel Pasaje, but we adhered to our resolution to go to the Hotel Inglaterra on condition that we should have front rooms.

A friend had bespoken rooms for us at the Hotel Pasaje, but we adhered to our resolution to go to the Hotel Inglaterra on condition that we should have front rooms.

The man from the Pasaje was greatly disappointed, and lingered about entreating us to go there, until the one from the Inglaterra was vexed, and turning round upon him, said, "They are going to Inglaterra, and would not go to the Pasaje for nothing;" this vehement reproof took effect and settled the matter. At seven we left the ship, and entering a boat with an awning over us in the stern and luggage in the bow, sailed pleasantly up to the Custom House.

In the large room of the Custom House we were in a busy throng of people, attracted by the arrival of our steamer: Cubans, Spaniards, Mexicans, Americans, Chinese, Mulattos, Negroes, and English. They were nearly all smoking cigars or cigarettes, and I heard many of them speaking English.

From the moment we signified our intention of going to the "Inglaterra," the energetic "runner" of that hotel took us entirely under his protection, and we had no trouble about the boat fare or porterage, and very little about examination of luggage or passports. It was a beautiful bright sunny morning, and first impressions of Havana were very agreeable. Just outside there were numerous little carriages for passengers, and mule carts for baggage, and after a few minutes' drive, mostly through narrow streets, we arrived at our hotel. The price of rooms and board, on the American plan, was a matter of bargain, and easily settled at three and a half dollars each per day, or about 14s. 6d. in our money. This is quite enough as we shall seldom want anything more than bed and breakfast in the house. I was induced to take a back room until to-morrow, when "a family will leave by the French-a steamer," and I can then have a front room as previously arranged.

and breakfast in the house. I was induced to take a back room until to-morrow, when "a family will leave by the French-a steamer," and I can then have a front room as previously arranged.

The Hotel Inglaterra is a fine building, situated in the Grand Prado, and facing the Parque de Isabel; the entrance on a level with the boulevard is through a corridor slightly partitioned off, and partly occupied by a cigar dealer and money-changer. All the rest of the ground floor, except the offices at the back, is a spacious dining-room set with small tables, all looking very neat and orderly.

On the first floor upstairs, the centre is a large saloon or anteroom with coffee tables, chairs, and couches. The windows open on to the verandah, where it is pleasant to sit and listen to the band in the evenings. To the right and left of this saloon are the bedrooms; these, to our English notions of comfort, are barely furnished and without carpets, but this may be partly owing to the hot climate. The spring mattresses of the beds are merely covered with canvas, and the "bedclothes" consist of a single thin sheet. Fine muslin mosquito-curtains are carefully closed all around the beds.

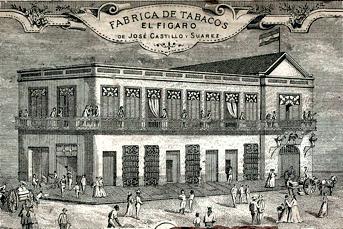

After breakfasting at nearly mid-day, we spent two or three hours in the cigar factory of Mr. Luis Marx, the present owner of the noted old brand of "Cabarga." Afterwards we called at Cabanas factory and made an appointment to meet Mr. Carvajal in the morning. When we returned to the hotel to dine at seven o'clock, Mr. Carvajal had already called and left his cards in acknowledgment of our visit.

Friday, October 24TH.

This morning we visited the great cigar factory of Cabanas, of world-wide fame, and met Mr. Carvajal, the present head of the firm, who took great pains to show us all about the treatment of tobacco and the art of cigar making.

This morning we visited the great cigar factory of Cabanas, of world-wide fame, and met Mr. Carvajal, the present head of the firm, who took great pains to show us all about the treatment of tobacco and the art of cigar making.

We then accepted his invitation to remain for breakfast, and had a very lively and pleasant time, being joined by several of his principal men.

Mr. Carvajal was surprised that I declined to have ice in my wine, and assured me "it was very good ice! that he was the president of the company for making it, and they sold it wholesale at a price equal to our halfpenny per lb." In reply, I said I had no doubt the ice was both good and cheap, but that good ice would not make good wine. The exchange of ideas in conversation, readily interpreted by Mr. Hunter, into Spanish and English, was sometimes very comical, and afforded much amusement.

The cigars to be smoked after breakfast were made fresh and brought up to the table, according to the usual custom.

In the afternoon we also visited the well-known cigar factories of "Larrañaga" and "La Intimidad," where we were politely received, and presented with a number of samples for trial. They are all very kind and generous in giving us cigars; immediately after our first arrival a box of the finest quality was placed in each of our rooms at the Hotel, and we have been liberally supplied since with a number of boxes.

After dinner at the hotel we took a carriage drive all about to see the city by gaslight; it looked bright and lively, and many sights were novel and amusing to a stranger.

Saturday, October 25TH.

To-day has also been devoted entirely to cigar business, visiting Villar's, and other principal factories, selecting samples and giving orders for shipment in December.

and giving orders for shipment in December.

My notes on tobacco culture in Cuba, and cigar making at Havana, give a few particulars that I have been able to gather on the subject from information and observation on the spot, and may be interesting to some of my friends.

………………………………..

The confident assertion, so freely made, that English and German cigars are sent out to Havana and returned with Havana brands and labels, has no foundation; in fact, it cannot be done, as the importation into Cuba of all foreign tobacco, manufactured or otherwise, is strictly prohibited.

The fictitious labels that appear on so many cigar boxes sold in the United Kingdom, are mostly imported imitations from other countries, in facsimile of noted brands, or with names and addresses that have no existence at Havana. It is almost needless to say that these fabrications purport to be made of tobacco of the Vuelta Abajo district.

Cigar making in all the best factories in Havana is done by men and boys, and mostly by piece-work. Some of the first-class workers, who make the fine sizes and shapes, earn high wages, and nearly all are very independent and difficult to manage. Sometimes they are careless in their work, and frequently stay away or leave their work at any hour without notice.

When at work their hats, coats, and vests, and frequently their shirts, are hung on pegs in the workrooms, which are large and well-lighted, and often looking out upon palms and other tropical plants in an inner open space in the centre of the factory.

The men and boys, sometimes 150 to 200 in one room, are seated in orderly rows, at tables with divisions without lids, like boys at our school desks.

The men and boys, sometimes 150 to 200 in one room, are seated in orderly rows, at tables with divisions without lids, like boys at our school desks.

Everyone is allowed to smoke, while at work, as many as he likes of the cigars he is making, and in this they appear to be wasteful, as large cigars, that had only been smoked a few minutes, are thrown down and lie about on the floor, all over the workrooms.

Cigar smoking in Havana is general among all classes and all day long, and is not confined to men only, but women are seldom seen smoking in the street, the exceptions being a few aged negresses.

Pipes are not smoked except by Chinamen and a few sailors; cigarettes are largely consumed, the bulk of them being made of "picadura" or chopped tobacco, the short cuttings, &c., from cigar-making.

Fine cigars are dear and not a matter of course, even at Havana, but they can always be got by going to the best fabricas. Connoisseurs smoke their cigars when fresh made, and prefer those with dark wrappers. When a gentleman invites friends to dinner, he calls at a factory and orders the cigars to be made the same afternoon; but there is no such thing known as green cigars, what is meant is freshly-made cigars.

Mr. Carvajal's favourite kind are made specially for him from leaves that have been allowed to ripen or mature on the plant, but I did not think them as fine and delicate in aroma as average Excepcionales.

Common cigars, such as are smoked by the lower classes, are made of very poor tobacco, and are comparatively cheap.

In Spanish, cigars are called tabacos, and cigarettes are cigarros, which is rather confusing to foreigners.

Really fine Havana cigars are not likely to be cheap again in the present generation, as the area of production of fine tobacco in Cuba cannot be extended, and the demand and consumption of the finest kinds increase year by year throughout the world.

After dinner a party of us drove to the Chinese Theatre, situated in a part of the city called the Chinese quarter, and a wretchedly poor and dirty quarter it is. We were politely received and shown to the front row of seats in the gallery, and an attendant immediately brought us each a glass of water and some "panales," for which he declined to receive either payment or gratuity. Panales are honeycomb sponge-cakes of white of egg and sugar, which dissolve on being dipped in the water, and make a kind of eau sucrée. As it was Saturday evening there was a large attendance, the ground floor being fully occupied by Chinamen only, who kept up a constant chatter amid a cloud of smoke. The dialogue of the performance was carried on in Chinese, pitched in a high, discordant key, that sounded most disagreeably like "cats on the tiles," and to us was neither intelligible nor comical, so we soon had enough of it. I understand their plays are chiefly historical, and go on for years.

Next we went to see a grand negro ball, held at a large concert and ballroom. There was some doubt whether we should be admitted, but, as usual, the dollars prevailed, and we ascended a wide stairs into a splendid room with a well-laid and highly-polished floor, and brilliantly lighted with gas. The guests, in a very orderly manner, were slowly arriving, and the presence of six or eight smart policemen seemed unnecessary. The brass band was loud and long, and the dancing very tame indeed.

The men were neatly dressed in black with white vests, and "extensive" in rings and watch-guards, and the women, gorgeously attired in clean prints and muslin dresses, wore large ear-rings and bangles, their plentiful and frizzy hair being piled high on their heads and decorated with bright ribbons.

In dancing, each couple only shuffled round four or five times on one spot, and then stood still for three or four minutes without speaking to each other; the men generally staring vacantly at the ceiling, or to some other part of the room; the women using their fans, and many of them smoking cigarettes. We expected to see some characteristic negro dances, and were informed it would get more lively towards eleven o'clock, so we adjourned for an hour. When we returned, the numbers had increased, but the same dull shuffling waltz was going on, and we soon retired from the scene.

The two principal theatres, which are very large, are not open at present, and the performances at a third seem very third-rate, and of questionable character; but being in Spanish, I am not competent to form an independent opinion.

Sunday, October 26th.

This morning we went by steam-tramcar to Chorrera, a pretty suburb on the coast, three or four miles off, to breakfast at Petit's noted French restaurant, and very pleasant it was on the open verandah, a dreadful plague of flies excepted.

at Petit's noted French restaurant, and very pleasant it was on the open verandah, a dreadful plague of flies excepted.

The cars were stopped anywhere to take up or set down passengers as ordinary tramcars. The tramroad, after the first few streets, is not used by other vehicles, but people walk along or cross it just as they please.

In front of the restaurant some poor men were fishing with rods, and waded into the sea up to their waists.

At Havana it is the custom to give their horses a good wash and swim in the salt water, almost daily, and this fine morning was more than usually devoted to it. For this refreshing bath they are strung together in great numbers. One negro was cleverly managing nineteen at once, all swimming about with little more than heads visible.

Being in Cuba one is expected to do as the Cubans do, and this afternoon we went to see a grand bull-fight, not without qualms I must admit, and on Sunday, too, above all days; but I am sorry to say that in Cuba there is no Sunday, as known and generally observed in England. In Cuba the great day for bull-fights, cockfights, balls, and grand spectacular performances is Sunday. Well, I have been to a bull-fight, and came away very much disgusted and disappointed with the amusement. Bull-fights may be better in Spain, but in Havana they are cruel and miserable exhibitions, without, as it appears to me, any redeeming feature.

The attractions of this particular bull-fight were placarded in the cafes and all over the walls of the city, and some renowned bull-fighters had come from Spain for the occasion. As all the world was going, excepting, I am glad to say, women and children, we started out at two o'clock, and were soon in the stream of people all eagerly hurrying on to the Plaza de Toros, or bull-ring. On the way the bull-fighters in gorgeous apparel passed us, some on horseback and some in chariots, and the mere sight of them seemed to inflame the crowd that was trying to keep up with them.

The press at the entrance to the ferry was so great, we prudently bought tickets at a high premium, for both ferry-steamer and bull-ring from a bawling speculator outside, and this settled, we buttoned up our coats and pockets, and pressed forward in a mixed crowd of people of all classes but the very poorest.

The press at the entrance to the ferry was so great, we prudently bought tickets at a high premium, for both ferry-steamer and bull-ring from a bawling speculator outside, and this settled, we buttoned up our coats and pockets, and pressed forward in a mixed crowd of people of all classes but the very poorest.

The "Plaza de Toros" is just like a large uncovered circus, and arranged in the same way, with tiers of plank seats all round, and with similar openings for entrance and exit. Over the entrance for bulls and horses, a sort of "royal box" was reserved for distinguished patrons, and a private box for the president and his attendants. The seats on the "shady side" (entrada á la sombra) were twice the price of those in the rays of the sun (al sol), and that was the only difference.

When we arrived there were already two to three thousand spectators, and the place continued to fill rapidly, until there were perhaps five thousand present.

On the arrival of the president there was a general stir of excitement, as without his presence the spectacle cannot begin; the entrance door was thrown open to admit a grand procession of performers. At the head of it was the key-bearer, gorgeously dressed in velvet, trimmed with gold lace, and a jaunty Spanish cloak over his shoulders, and mounted on a beautiful prancing charger. Next came the two picadores or lancers, also mounted on horses, but these were poor, weak, wretchedlooking animals, not worth more than fifty shillings each, and dear at three pounds. These men had their legs either encased in iron or thickly wadded and then covered with chamois leather; they wore jackets and vests of velvet, grandly trimmed with gold lace, and flatlooking hats decorated with feathers. Then the dartmen (los banderilleros) followed on foot, also attired in velvet and gold, knee-breeches, white silk stockings, and low shoes with bright buckles, their jet black hair tied in a knot at the back, and velvet cap and feathers.

The two swordsmen (matadores or espadas) came next, also in short velvet jackets, richly trimmed with gold lace, knee-breeches, and pink silk stockings. Last of the procession were three Spanish mules yoked together with splendid harness, and with bells and gaudy tassels about their heads; these were driven by men in short jackets, white trousers, and coloured silk handkerchiefs round their heads.

After marching once round the ring the key-bearer reined up in the centre and saluted the president, who threw the key to him from his box over our heads; it was cleverly caught, the bugle sounded, and the ring was then " open." The key-bearer and picadores retired, and the mules were led out, leaving all the rest in the arena to wait for the bull. In a few moments the first one came running tamely in, two or three darts with gay ribbons sticking in his neck to make him lively.

He was a poor little beast, and looked quite bewildered at the banderilleros and matadores, who pranced about, passing bright, gaudy silk cloaks before his eyes to attract his attention from one to another. If he made a rush the men slipped sideways behind wooden screens erected for their safety inside the barrier of the arena, or they jumped over the barrier to get out of his reach. When the bull was thus excited the picadores re-entered on their blindfolded, wretched-looking, little white horses, and almost stood still to let the bull run at them and butt or gore the horses, without tilting at him with their lances, or making any show of resistance. This most brutal part of the performance was repeated with one or other of the horses several times, until one of them was deeply gored in the flank.

The excitement of the spectators was then intense, many rising to their feet, and, amid loud yells and calls to the president for los banderilleros! from hundreds of throats, the bugle was sounded, and the picadores retired on their poor trembling horses.

The "fight" was then continued by the banderilleros and espadas, who had to resort to further torture to enrage the bull. For this purpose darts (or banderillas) were brought to the men; these are like thin arrows, about two feet long, pointed with steel barbs, and decorated with frills of fancy-coloured paper. One of the banderilleros took a dart in each hand, and, facing the bull, dodged nimbly about for two or three minutes, watching for an opportunity, and when the bull was making a run at him he quickly stuck them into his shoulders, one on each side, and jumped aside to let the bull pass. This was repeated by the other dartman with a great show of danger and difficulty, and now four darts were dangling from his shoulders, and small streams of blood running from the wounds.

For this purpose darts (or banderillas) were brought to the men; these are like thin arrows, about two feet long, pointed with steel barbs, and decorated with frills of fancy-coloured paper. One of the banderilleros took a dart in each hand, and, facing the bull, dodged nimbly about for two or three minutes, watching for an opportunity, and when the bull was making a run at him he quickly stuck them into his shoulders, one on each side, and jumped aside to let the bull pass. This was repeated by the other dartman with a great show of danger and difficulty, and now four darts were dangling from his shoulders, and small streams of blood running from the wounds.

The bull, now stupefied and foaming at the mouth, stood still for moments, or made weak attempts to get at his tormentors. By this time he was nearly exhausted, the bugle was again sounded, and one of the matadores immediately appeared with a scarlet cloak on his left arm, and a sharp sword in his right hand, with which to put an end to his pain. This skilful swordsman was a noted bull-killer from Spain, and a very fine-looking, well-built man for such a performance. After a bow to the president, he began to dance about with great agility and show of difficulty and danger in his dreadful purpose;  the bull made a few more feeble runs at the red cloak, and then, at a moment when he stood and lowered his head, the sword was dexterously thrust through the shoulder to his heart, and he dropped on his knees dead. The matador was loudly cheered, the team of mules was instantly hurried in, a rope passed round the horns of the bull, attached to the traces, and the animal was dragged out of the ring. At the same moment another bull, a rather finer and more ferocious looking animal than the first, was admitted, and the exhibitions of skill repeated exactly as before, except that the matador was not quite as skilful or expert as the first, and made several unsuccessful attempts to kill the bull; sometimes leaving the sword dangling with the point sticking in the flesh; but at last he also fell, and the assistants finished the business somehow.

the bull made a few more feeble runs at the red cloak, and then, at a moment when he stood and lowered his head, the sword was dexterously thrust through the shoulder to his heart, and he dropped on his knees dead. The matador was loudly cheered, the team of mules was instantly hurried in, a rope passed round the horns of the bull, attached to the traces, and the animal was dragged out of the ring. At the same moment another bull, a rather finer and more ferocious looking animal than the first, was admitted, and the exhibitions of skill repeated exactly as before, except that the matador was not quite as skilful or expert as the first, and made several unsuccessful attempts to kill the bull; sometimes leaving the sword dangling with the point sticking in the flesh; but at last he also fell, and the assistants finished the business somehow.

I was now satisfied with the "sport" and we tried to get out, but before we managed to do so a third bull was done to death in the same manner, and three more were to follow.

Through the whole affair there is no sense of fear for the men, who are all fine, active fellows; one's sympathy in a most unequal combat is all for the bulls, and one's pity for the poor horses. It appeared to me that a good big shorthorn bull, such as we often see in England, would have knocked the whole place to pieces in a few minutes, and I am told that some large Texas bulls were actually brought over for a grand occasion, and the bull-fighters declined to encounter them.

large Texas bulls were actually brought over for a grand occasion, and the bull-fighters declined to encounter them.

Such is the spectacle, as I saw it, of a grand bull-fight at Havana, upon which I shall not attempt to moralise, as the Cubans might make unfavourable comparison with some of our national sports.

It was a great relief to get out of the place, and in recrossing the beautiful harbour on our way to Havana it was pleasant to find we had the steamer almost to ourselves.

To help to dispel the scene of the Plaza de Toros, we took an open carriage drive in the grand Paceo, halting at the Captain General's Palace for a stroll under the shady trees, and where, if the truth were known, some fragrant "Excepcionales" contributed to our enjoyment.

Monday, October 27TH.

This morning, after spending an hour or two on cigar business at Cabanas' offices, Mr. Carvajal took us a drive in his open carriage to see a large new cemetery in the suburbs, and especially to see an immense tomb he has recently had made for his family. The blocks of polished granite from the United States are an enormous size and weight, and the interior is constructed as a beautiful small chapel. We were afterwards told it had cost him 10,000 dollars (gold) and 3,000 more for the removal of the granite slabs from the ship to the cemetery; special wagons having to be made to convey them.

This morning, after spending an hour or two on cigar business at Cabanas' offices, Mr. Carvajal took us a drive in his open carriage to see a large new cemetery in the suburbs, and especially to see an immense tomb he has recently had made for his family. The blocks of polished granite from the United States are an enormous size and weight, and the interior is constructed as a beautiful small chapel. We were afterwards told it had cost him 10,000 dollars (gold) and 3,000 more for the removal of the granite slabs from the ship to the cemetery; special wagons having to be made to convey them.

"And so sepulchred, in such pomp dost lie, -

That kings, for such a tomb, would wish to die."

After dinner Mr. Carvajal called for me at the hotel to go to the Grand Spanish Casino, of which he has been president the last four years. It is a large handsome building, looking on to the Parque de Isabel; it contains spacious rooms for reading, billiards, balls, committees, and for all the purposes of a great political and social club.

Mr. Carvajal is a most affable and courteous gentleman, and said to be the most popular man in Havana; everywhere in the streets he receives most friendly greetings, and at the Casino he appears to be beloved by the members, who flock around him, shaking hands right and left, as though they had not seen him for a month. He is an active and loyal supporter of the Spanish government in Cuba. By his portrait in the club, I see his full name and title is, His Excellency Don Leopoldo Carvajal, and when in full dress he wears a number of handsome "decorations" from the Court of Madrid.

popular man in Havana; everywhere in the streets he receives most friendly greetings, and at the Casino he appears to be beloved by the members, who flock around him, shaking hands right and left, as though they had not seen him for a month. He is an active and loyal supporter of the Spanish government in Cuba. By his portrait in the club, I see his full name and title is, His Excellency Don Leopoldo Carvajal, and when in full dress he wears a number of handsome "decorations" from the Court of Madrid.

Tuesday, October 28th.

At ten o'clock Mr. Carvajal called for an "early" breakfast with us at the hotel, and then took us in a carriage and pair about six miles into the country, to see the great water spring at Vento, and the Havana waterworks, which were begun many years ago on a magnificent scale, and stopped for want of money, when the principal works and three miles of aqueduct had been well made under an eminent American engineer. For the last four years not a cent has been spent in further construction, and 400,000 dollars is still owing to the first contractor. Mr. Carvajal is the president or chairman of the undertaking, and for want of funds is quite powerless to go on with the work, though the water is greatly needed in the city. The volume of water, which never fails or varies winter or summer, is so great that it has been calculated to be sufficient to supply a population twice the size of London. It is supposed, or has been proved, to come under the gulf from Florida, as it exactly agrees in analysis with a lake or stream of water which there disappears in the earth. At our visit the waste sluice was closed and the great basin over the spring filled, and another sluice opened to allow the water to flow down the aqueduct, filling it continuously about four feet wide and deep. I have never seen a large stream of water so beautifully clear and so pure in taste.

On the way out we drove past thousands of tall palmtrees, like huge feather dusters, thirty to forty feet high, rows of cocoa-palms with fruit on, bananas with clusters of fruit nearly ripe, hedges covered with convolvulus, and the poinsettia pulcherrima in full bloom, and lovely flowers I could not distinguish; yuccas and aloes were also plentiful in the roadside hedges.

The cocoa-palms are dying in great numbers from the ravages of an insect like a large cockroach, which attacks the core, and causes the fronds or branches to turn from green to pale yellow or straw colour, and then they drop off; "when they decay the core smells like putrid meat."

The cocoa-palms are dying in great numbers from the ravages of an insect like a large cockroach, which attacks the core, and causes the fronds or branches to turn from green to pale yellow or straw colour, and then they drop off; "when they decay the core smells like putrid meat."

We also passed a sugar plantation which produces eight to ten thousand hogsheads a year.

The sun was extremely hot, so we were glad to keep the carriage-hood over our heads all the way.

We met a number of rude carts, each with four to six mules yoked tandem, bringing country produce into Havana market. It is more generally brought on the backs of mules in large baskets made of matting or palm leaves. Live fowls and turkeys are sometimes brought in crates, but are frequently slung by the legs in large bunches over the backs of mules, and the poor things are also hawked about the streets in the hands of men and boys. I noticed that if any fowl uttered a caw of distress, they swung the lot sharply round, to silence the culprit who ventured to complain of the treatment.

In a hot climate to "kill and eat" is the custom, and it is no uncommon thing to see poultry brought in alive and on the table for dinner an hour after.

…………………………….

Thursday, October 30TH.

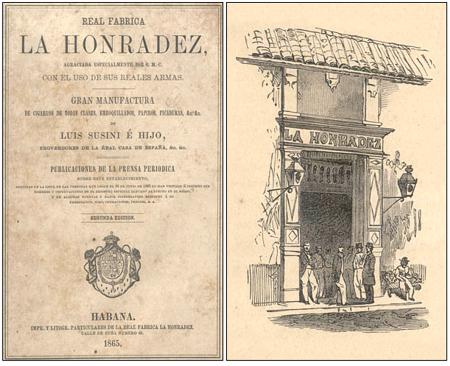

This morning we visited the great cigarette manufactory, "La Honradez," and were particularly interested in a most ingenious and beautiful American machine for making cigarettes. A continuous band of fine paper is regularly supplied with the requisite quantity of cut tobacco as it passes on through a tube, where it is neatly folded, fastened, and then cut off in the exact lengths required, as fast as they can be carried away to make into packets.

ingenious and beautiful American machine for making cigarettes. A continuous band of fine paper is regularly supplied with the requisite quantity of cut tobacco as it passes on through a tube, where it is neatly folded, fastened, and then cut off in the exact lengths required, as fast as they can be carried away to make into packets.

The remainder of my time this morning was spent in paying farewell calls, including a very pleasant visit to the Chinese Ambassadors. They speak English fluently in sweet musical voice, without any peculiarity of accent. I had the pleasure of taking a cup of fine tea with them in the native fashion, and of exchanging cartes-de-visite.

We have been comfortable at the Hotel Inglaterra, and can recommend it; the dining-room menu both for breakfast and dinner is on a liberal scale, and the service good.

Mr. Crowe, the English Consul-general, and friends, who know their way about pretty well, give the Inglaterra the preference for dining. In the bedrooms we are attended to by men; a mulatto and a negress chambermaids are occasionally seen about the anteroom, but at the approach of strangers they droop their large black eyes and disappear.

In answer to my occasional inquiries, the "runner" always informs me "the French-a steamer has not come as expected," so I have not had the offer of a front room as stipulated, and no explanation or apology is volunteered at the office. The hotel Pasaje has much finer rooms than the Inglaterra, and the "Telegrafo" is also spoken of as one of the best.

In answer to my occasional inquiries, the "runner" always informs me "the French-a steamer has not come as expected," so I have not had the offer of a front room as stipulated, and no explanation or apology is volunteered at the office. The hotel Pasaje has much finer rooms than the Inglaterra, and the "Telegrafo" is also spoken of as one of the best.

In a visit only extending over a single week a full description of Havana, and of the manners and customs of the people could not be expected; yet to give some idea of the place, while my memory is fresh, I may briefly add a few observations to my diary.

The population of about 250,000 is very mixed, including a large proportion of people of all shades of colour, from the genuine dark negro to pale olive mulatto. The latter are variously described as octoroons, quadroons, "or coffee and milk" and "yellow pines," &c There are in Cuba, and chiefly in Havana, 60,000 Chinamen and no Chinawomen; the negroes and Chinamen being chiefly employed in domestic service and doing all kinds of menial and laborious work.

The Captain-General is governor of the island and military chief, and his authority is supported by a large army of about twenty thousand men. He is appointed for three years, and seldom exceeds his term of office; he has a palace and splendid stables in the city, and a summer residence with large garden and well-wooded pleasure grounds in the suburbs. Sometimes he is popular and gives grand entertainments, and sometimes the reverse, and makes all he can by the position, including fees and bribes right and left.

In Havana, life and property are protected by a numerous body of smart, military-looking police, both mounted and foot, who, always two and two, patrol the city and suburbs armed with swords and large pistols, as robberies with violence are frequent and quickly executed.

When the desperadoes who commit these assaults do fall into the hands of the police, and offer resistance in capture or conveyance to the lock-up, it is said they are shot without much hesitation, and taken in dead; a declaration that the prisoner attempted to escape, and that they were obliged to shoot him, being sufficient. However, I am glad to say that during my visit I have not seen any altercation or a single drunk or disorderly person.

conveyance to the lock-up, it is said they are shot without much hesitation, and taken in dead; a declaration that the prisoner attempted to escape, and that they were obliged to shoot him, being sufficient. However, I am glad to say that during my visit I have not seen any altercation or a single drunk or disorderly person.

I was informed that the pay of the police is often eight or nine months in arrears, and that of the army and navy for a much longer period.

The Cuban ladies are generally small and genteel, and a great majority are pretty, but nearly all of the same type of beauty: black hair, fine dark eyes, regular features, and pale faces. They dress well, and when out of doors wear a mantilla of black lace loosely over the head and shoulders. The men are generally handsome and slender, smartly dressed, and walk erect with elastic step.

Many of the young negresses and mulattas are tall and handsome, and march along with a jaunty air and heads erect. When I remarked that I did not see any elderly women of the same stamp, I was told "they generally die of consumption."

The few aged black women to be seen in the streets are mostly short, stout, and ugly; but the most miserable objects of human beings I have ever seen are the Chinese cripples and beggars in Cuba. Many of the wretched creatures look like mere skeletons covered with parchment.

Business men, as a rule, take when dressing only a cup of chocolate or cafe con leche (coffee with milk), then go to their offices for three or four hours, and return to breakfast at from eleven to twelve. They rest during the heat of the day, and revisit their business later on. At seven they dine, and after that, say from eight to ten, they sit in the open air or promenade and listen to the fine military bands that play in the fashionable Parque Isabel nearly every evening. There it is you see welldressed ladies and gentlemen in thousands promenading every evening, or sitting on chairs provided, which are charged for exactly as at Rotten Row. Pretty little dark-eyed children, beautifully dressed in muslins and bright sashes, are also there in hundreds, either walking hand-in-hand with their parents or playing and romping about until a late hour in charge of a black nurse, having probably been kept indoors during the heat of the day. To these open-air concerts many ladies come on the Prado in open carriages and do not alight, in which case the mantilla is often not worn and the arrangement of the hair is then a triumph. The coachmen are nearly always negroes in gorgeous livery.

Business men, as a rule, take when dressing only a cup of chocolate or cafe con leche (coffee with milk), then go to their offices for three or four hours, and return to breakfast at from eleven to twelve. They rest during the heat of the day, and revisit their business later on. At seven they dine, and after that, say from eight to ten, they sit in the open air or promenade and listen to the fine military bands that play in the fashionable Parque Isabel nearly every evening. There it is you see welldressed ladies and gentlemen in thousands promenading every evening, or sitting on chairs provided, which are charged for exactly as at Rotten Row. Pretty little dark-eyed children, beautifully dressed in muslins and bright sashes, are also there in hundreds, either walking hand-in-hand with their parents or playing and romping about until a late hour in charge of a black nurse, having probably been kept indoors during the heat of the day. To these open-air concerts many ladies come on the Prado in open carriages and do not alight, in which case the mantilla is often not worn and the arrangement of the hair is then a triumph. The coachmen are nearly always negroes in gorgeous livery.

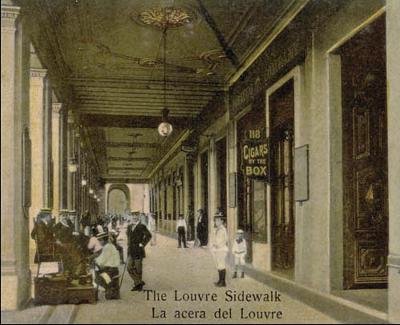

In the morning ladies are seldom seen out, except occasionally for shopping, and then the best class are always accompanied by a negress, who rides side by side in the Victoria, or, if walking, keeps at a respectful distance behind. In the evenings the grand cafes, especially the Louvre next to the Hotel Inglaterra, are thronged with gentlemen smoking and talking with great animation. They take a variety of cooling drinks, which are a speciality in a climate where they have perpetual summer.

The public conveyances are mostly one-horse Victorias for two persons; they have hoods and curtains to protect from the sun, and the fare is twenty cents (paper), or equal to fivepence per single journey; there are also open barouches, with two horses, for four persons. On a few main routes tramcars and omnibuses, drawn by miserable-looking horses or Spanish mules, run frequently at cheap rates. The horses and mules in harness are provided with large tassels about the head to keep off the troublesome flies.

the sun, and the fare is twenty cents (paper), or equal to fivepence per single journey; there are also open barouches, with two horses, for four persons. On a few main routes tramcars and omnibuses, drawn by miserable-looking horses or Spanish mules, run frequently at cheap rates. The horses and mules in harness are provided with large tassels about the head to keep off the troublesome flies.

For shade from the sun the streets of Havana have been purposely made very narrow, excepting only a few squares or open spaces, and the grand Prado or wide boulevard that divides the old part of the city from the more modern. The footpaths on each side are so narrow that people can walk along them only in single-file.

There is no select residential quarter of the city, the best family houses being scattered about among the business premises, and often adjoining very objectionable neighbours. In such situations it is of course impossible to have nice gardens and pleasure grounds to the houses, as in our suburbs; the best they can do is to have handsome palms, &c., in their spacious courtyards. The flat housetops are also available for plants, and for a cool seat in the evenings.

Charcoal is used for cooking purposes, and as no house fires are required there is no smoke, and consequently the city may be said to be without chimneys.

Charcoal is used for cooking purposes, and as no house fires are required there is no smoke, and consequently the city may be said to be without chimneys.

The grand Prado or Paseo has, in addition to a broad carriage drive which runs right down to the sea, convenient walks and paths among beds of shrubs, palms, and tropical trees.

The ancient city was formerly protected by very thick walls of stone and cement, and guards were mounted at the handsome entrance gates. These old walls have been in course of demolition for thirty years, and a gentleman said to me: "At Havana everything goes slow; we have no money to spare for such work."

The best shops are in the streets Obispo, Ricla, and O'Reilly. They are open to the footpaths and attractively arranged in a bazaar-like fashion; the stocks are comparatively small and not of great value. A gay appearance is imparted to some of these narrow streets, by awnings stretched from side to side to shade from the sun.

The streets are badly paved with stone setts, which have to be imported from America, and consequently are very expensive. The insanitary "modern conveniences" indoors and the drainage outside are very defective, and in a tropical climate one is almost thankful that the germs of zymotic disease are not festering in imperfect sewers. In the more modern portion of the city many of the streets remain year after year in deep holes and ruts, neither paved nor sewered.

expensive. The insanitary "modern conveniences" indoors and the drainage outside are very defective, and in a tropical climate one is almost thankful that the germs of zymotic disease are not festering in imperfect sewers. In the more modern portion of the city many of the streets remain year after year in deep holes and ruts, neither paved nor sewered.

The streets are swept by negro scavengers, and domestic refuse of all kinds is set out in tubs in the streets, to be removed during the night. Assisting the scavengers in the removal of offal refuse in the city are hundreds of large carrion-birds, like cormorants, flying about almost tame, and under the special protection of the city authorities.

The markets are well supplied with fruit, vegetables, fish, and poultry, and the banana in great abundance, which may be said to be the bread of the poor of Cuba.

The markets are well supplied with fruit, vegetables, fish, and poultry, and the banana in great abundance, which may be said to be the bread of the poor of Cuba.

Hawking in the streets is carried on to a great extent. Sometimes the baskets or hampers are carried in hand or on the head, but more generally on the backs of mules, on which men sit swinging lazily along, calling out their speciality just as one hears in London. In this way all kinds of bread, fish, fruit and confectionery, live fowls, quails, &c., are distributed. In many public places Chinamen are standing at tables and stalls on tressels, set out with curious cakes and sweetmeats, over which they instinctively keep waving a light feather plume or common fan, to keep the flies off. I noticed scores of these stalls and never once saw a customer stop to buy anything.

Fresh milk is supplied from cows kept standing on the shady side of streets, here and there, in convenient places all over the city; often half-a-dozen together, and always have with them their pretty fawn-coloured young calves.

In offices, factories, and workrooms, drinking water is kept cool in large brown clay, unglazed, pilgrim jars, with a handle at the top and narrow spout at the side, from which water is poured into the mouth without touching the spout with the lips. I tried it once, and the first part of the refreshing stream was spilt all over my shirt front.

at the top and narrow spout at the side, from which water is poured into the mouth without touching the spout with the lips. I tried it once, and the first part of the refreshing stream was spilt all over my shirt front.

The shoeblack boys of Havana look very sharply after business at all likely places, and particularly at the doors of hotels and restaurants. They are permitted to come into the dining-rooms among the tables, to "shine your boots" as you sit at dinner.

The lottery ticket nuisance, the curse of Cuba, is the worst of all. From the first moment of setting foot on shore until the last before leaving, lottery tickets, lottery tickets, lottery tickets are fluttered before one's eyes at all places, and at all times—morning, noon, and night. Old men, old women, and children, at cigar shops, ticket offices, everywhere, push them under notice, and one cannot escape them. At Matanzas it was just the same; the instant we got out of the railway-car the lottery ticket vendors rushed up to us, confident that we could not possibly have gone there for any other purpose than to buy lottery tickets. I understand these Government lotteries of 25,000 tickets, of forty dollars (paper) each, and subdivided into tickets of one and two dollars, take place about every twelve days all the year round. In the way  described, speculators in the tickets dispose of as many as they can, perhaps ten or fifteen thousand. The rest of the chances remain in the hands of the Government, who also take twenty-five per cent of the gross amount of each lottery. The expectation of some day drawing a grand prize is sufficient to keep up the excitement among all classes, down to the poorest workmen who can manage to buy or join in buying a ticket in divided shares.

described, speculators in the tickets dispose of as many as they can, perhaps ten or fifteen thousand. The rest of the chances remain in the hands of the Government, who also take twenty-five per cent of the gross amount of each lottery. The expectation of some day drawing a grand prize is sufficient to keep up the excitement among all classes, down to the poorest workmen who can manage to buy or join in buying a ticket in divided shares.

Havana has natural advantages for commerce in its beautiful large harbour, with water deep enough for the largest vessels, and in a climate of perpetual summer. Of the fertile soil of the Island of Cuba, the chief products are sugar, tobacco, and coffee, and on these industries, directly or indirectly, the population of Havana mainly depend. It also grows a great quantity of fruits, such as bananas, cocoa-nuts, pines, limes, oranges, guavas, and green mangos; but for berry fruits of all kinds the climate is too hot, and they are consequently small and shrivelled. Of vegetables may be mentioned sweet potatoes, cabbages, onions, and garlic; the strong odour of the latter is constantly met with among the working-class and is very offensive.

The food supply is considerably supplemented by a great variety of fish caught at Havana, and all around the coast. Sharks are numerous, and shark-shooting is one of the exciting sports; oil is extracted from them, and the smaller ones are eaten.

On our return voyage we have in the cargo 1,200 hogsheads of sugar for New York, and 183 cases of cigars for America, England, and Germany; the steamer since our arrival having been to Cardenas to take the sugar on board. We have also a large quantity of fruit, especially bananas.

We have also a large quantity of fruit, especially bananas.

The currency is in paper notes of the nominal value of five cents and upwards, and in gold ounces and halfounces; the paper money is worth in gold less than half the amount stated upon it. For instance, in change for a gold ounce of seventeen dollars, I received a few cents over thirty-eight dollars in paper. Hence in all money matters, it is necessary to quote prices, so many dollars gold, or so many dollars paper; because if you simply say, "I gave ten dollars for this straw-hat," it would not be understood whether it cost twenty  shillings or something under ten. These pretty little notes, not much larger than a gentleman's visiting card, get very worn and dirty, and roll up into little pellets in one's pockets very inconveniently.

shillings or something under ten. These pretty little notes, not much larger than a gentleman's visiting card, get very worn and dirty, and roll up into little pellets in one's pockets very inconveniently.

Havana has modern London fire-engines and a smart fire-brigade.

Life in Havana during the hot season is very trying to Europeans, mosquitos and other insects being very troublesome, and there is great liability to yellow fever. My stay of a few days in the cool season, among novel sights and sounds, has been exceedingly interesting and pleasant, and leaves a strong desire to come again, and make excursions to other parts of the Island.

I am returning in the "Saratoga" to New York, and Mr. Hunter is staying another week for business at Havana.

We came off to the steamer in a sailing boat, just as we were first taken ashore. Mr. Carvajal, Mr. Marx, and Mr. Hunter came on board to see me off, and went ashore at five o'clock, when we left the harbour.

John Mark. Diary of my Trip to America and Havana. Second Ed. Manchester, London: Simpkin, Marshall, & Co., 1885. 40-73