The Spectacle of Rags: Tradition, Aesthetics, and Ideology in the Photographic Series “Tipos populares” by Cruces and Campa

Marco Martínez, Princeton University

The objective concept of mechanical reproduction allowed photography, well into the 20th century, to serve as the advocate of the Truth: the mechanical was science and science was truth. For the political sectors of Mexican liberalism in particular, photography came to be the medium that best meshed with their desire for the nation’s modernity. Therefore, the different photographic studios that opened in Mexico City constituted the pilgrimage site for the incipient bourgeoisie that consequently molded its varied dreams around a modern identity.(1)

Thus, though it did not yet represent a politically fortified group, the Mexican bourgeoisie of the 19th century used photography as a tactic in its effort to self-define its role in the modern scheme of national power. To construct this definition of identity, 19th century bourgeoisie photography used the representation of opposites, that is, us / them or bourgeois / popular classes.(2) To the degree that the local bourgeois imagined itself and recreated itself through the modern European experience, it was also necessary to locate and define that which was considered its opposite: the popular urban and anonymous subject, or “popular type.” In this way, the photographic studio—dedicated in the beginning to those who wore top hats and large crinolines—began to portray the sectors of society that lived at the margin.

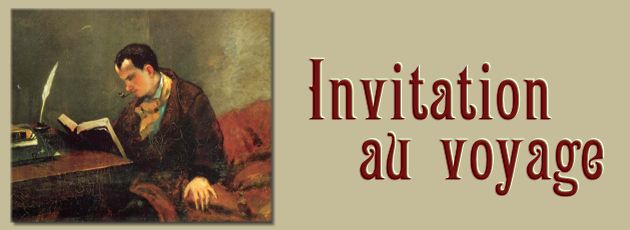

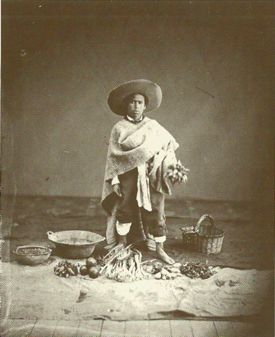

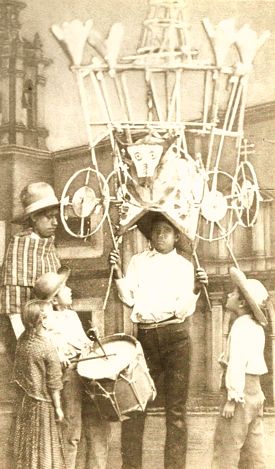

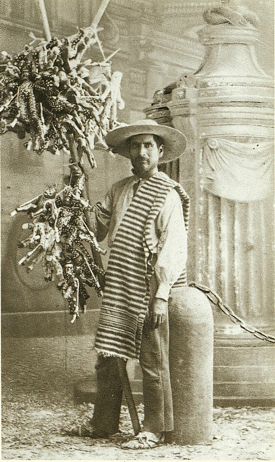

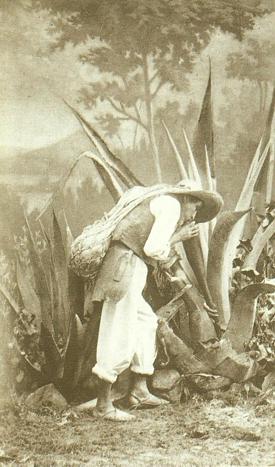

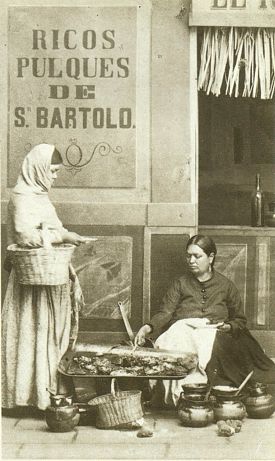

This definition of the supposedly unique bourgeois-modern identity is the topic of what follows, in particular the photographic series “Tipos populares,” by Antíoco Cruces and Luis Campa.(3) Inscribed in a well-established tradition of representing of popular characters—which began as far back as the caste portraits produced during in the colonial period—this series is distinctive insofar as it distances itself from the previous archeologizing photographic gaze to adopt an aestheticizing view of marginal subjects. In other words, in previous photographic series on popular types, subjects were accessible to the scrutinizing gaze: they preserved certain conditions of clothing and hygiene and appeared before a blank background (Image 1). The innovative aspect of Cruces and Campa’s photographic media was their desire to embellish those subjects, in their aspect as well as their poses for the image. In this way, in terms of their content and form, they were tied to the tradition of caste portraits; while in their media and purpose they coined technical directives from the aesthetics of bourgeois photographic portraits (Images 2 and 3).(4)

I propose that the main purpose of this aestheticizing view of popular types, within the political context of Mexican liberalism, was to serve as a medium for learning about the nation as well as about the subjects comprising it. For this reason, photographers like Cruces and Campa strove to create virtues and disguise defects. On the other hand, the medium functioned also as an element of cohesion for Mexican society, under the principle of national, modern identity. To understand this sinuous mixture of image-aesthetics, tradition, and the nation’s modernizing project, it is important to remember that, among 19th century liberals, the description of popular types and customs was understood as a service to the nation and its citizens.(5) That is, from this view of political liberalism, if every constitutive subject of the body of the nation appeared aligned with modern parameters—systemized economic production, moral well-being, elegance, and decorum, for example—it was concluded that modernity had arrived, or, at least, was in proximity. Of course, this modern presentation of these popular types was not to interfere with the hierarchical social order in Mexico. Subjects therefore appears encoded in his or her corresponding place while—as in the case portraits—they project a resigned or contented acceptance of their occupation or social position. Therefore, in Cruces and Campa’s photographic series “Popular Types,” we see one of the first political uses of photography in Mexico.

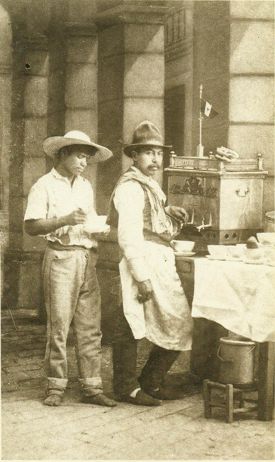

In order to analyze these points, I observe the use that photographers made of bourgeois aesthetics in order to portray popular types, particularly in the photographs “El vendedor de Judas,” “El tlachiquero,” and “La vendedora de quesadillas” from Cruces and Campa’s series (Images 4, 5, and 6). The popularization of photographic portraits also brought about the creation and systematization of a bourgeois aesthetic, which can be summed up in eight points:

- The development of the image in its entirety, with forms perfectly indicated.

- Agreeable physiognomy, natural pose.

- Overall sharpness.

- Shadows, halftones, and light well pronounced, the latter bright.

- Natural proportions.

- Details in the shadows.

- Purity and cleanness of the image.

- Natural backgrounds; avoidance of artificial and nuanced backgrounds that make the contours hard and discordant.(6)

I should clarify, however, that by analyzing these aesthetic details, I do not seek to focus solely on the constitution of the image as artistic event. As I have indicated, I am also interested in studying how that event is related to the liberal political imaginary. Further, I hope to perceive how, in the process of production, circulation, and collection of these photographs of popular types, the everyday practices of different sectors in Mexico City were addressed. It is interesting to note that the success that also brought about the creation of a unique aesthetic for photographic portraiture encouraged “a sterilization of the image, an asepticization for consumption that allowed for its popularity.”(7) Nevertheless, the aesthetic of the bourgeois portrait standardized photographic content, which led to an individual experience that gave way to the creation of the portrait as being supplanted by the social experience of possessing a portrait. This is why 19th century portrait photography lost any ability to create a strictly personal seal. Therefore, a critical view of photography becomes a historical type of reflection related to, but in excess of, purely artistic analysis.

Why was this series so well liked? What aesthetic—and political—elements grabbed the purchasers’ attention? In the 80 photographs of Cruces and Campa’s “Popular Types” series, we find that the characters portrayed have agreeable features, appear good-natured, and do not possess a gaze that challenges the spectator. The use of light diminishes shadows and avoids contrasts so that the person photographed features boldly in the foreground over any other element of the image, thereby occupying the greatest portion of the available visual space. The backgrounds and décor, although obviously fake, are in proper proportion with the subject of the portrait and are the elements that accompany the subject, specific to their vocation, which designate a place on the social scale. The poses are conventional, either facing forward or three quarters view, and always portray a relaxed state, which refers to the idea of elegance in bourgeois portraiture. It is worth pointing out, furthermore, that when the character appears on a second plane—as, for example, in “La tamalera,” (Image 7) “La vendedora de chia” (Image 8), “La buñuelera” (Image 9), or “La vendedora de quesadillas” (Image 6) — the first plane is occupied by different iconographic elements that are specific to the character’s activity.

It is important to spend some time on the analysis of the photographic backgrounds because much of the symbolic struggle between modernity / tradition, liberalism / conservatism is found in them. The different scenes seek to represent the places in which the popular types move, sites in Mexico City—the so-called “City of Palaces”—which, following the logic of the photograph, produce a utopian social space: clean and picturesque.(8) It is important to mention that these places, inhabited by those same popular characters, had previously been integrated into the representation of Mexico City in literature. However, contrary to Cruces and Campa’s photographic project, examples such as El periquillo sarniento (1816) by José Joaquín Fernández de Lizardi, Life in Mexico During a Residence of Two Years in that Country by Madame Calderón de la Barca (1843), or Crónicas de la semana (1850 – 69) by Ignacio Manuel Altamirano, depicted a city that was far from being the “City of Palaces.” These works conveyed a filthy city, full of social friction, in which the rich and the poor lived side by side.(9) In these literary works, poverty is seen with a mix of exoticism, discovery, and social criticism.

Two photographs serve to exemplify the beautification of the city in the “Tipos populares” photographic series: “La vendedora de quesadillas” (Image 6), and “El vendedor de Judas” (Image 4). The first photograph is composed of four elements: (1) the vendor, who is seated on the right side preparing the food; (2) the place where the vendor undertakes her occupation, which is located in the center and contains the metonymic elements that place the vendor (pots, baskets, a burner, and a griddle full of quesadillas); (3) a female client, who is on the left side, waiting for her order; and (4) a sign, in the background, which reads “Delicioso pulque de San Bartolo” and which, with its inscription, locates the scene in front of a pulquería. It is precisely this last element that makes the intention of the aestheticizing gaze on the urban social space explicit. In the 19th century, and still today, the pulquería was seen as a place of perdition, drunkenness, and low morals.(10) However, the photograph shows a pleasant, clean place, in which a woman could work without concern and, at the same time, any client could go without being bothered. This urban imaginary is reinforced by the perfect order and cleanliness of the walls, the paving of the street, and the vendor’s work utensils.

In this beautified place, the two women’s composure and good taste, even in the small details, stands out. Both dress “decently,” using a skirt that covers down to the ankles, a long-sleeve shirt that is buttoned down to the wrists and up to the neck, and both have their hair pulled back. The vendor uses an apron, which is necessary for her work, and the client a shawl that covers part of her head and back. This portrait of “decency” reminds us of the manuals or urbanity that circulated during this period, in which good dress and decorum were promoted for all social classes: “it will never be legal to omit any of the expenses or care that are indispensable to avoid poor hygiene, without regard for our social condition.” For 19th century eyes, both women dressed with “composure, dignity, and decency.”(11)

On the other hand, this image leads us to the absolute supposition, a characteristic of the 19th century, according to which poverty was not understood as a derivation of a structural condition, but rather as a question of morality and will. Dressing in accordance with the possibilities that individual work provides each person would lead not only to a better standard of living but also to a better moral level in a society that sought to reconcile certain traditional values with the paradigm of modern progress.

The second example comes from the photograph “El vendedor de Judas.”(12) This image is made up of just one character, the vendor, who is recognized by the product he sells, the effigies of Judas. The Judas vendor is presented as a character with mestizo skin color, dressed in pants, a shirt, a hat, a shawl or zarape, and traditional sandals. He is standing, leaning against a stone post in the middle of the street. “El vendedor de Judas” is represented outside the Metropolitan Cathedral. We know this because of various details: first, the post he leans up against is one of the ones around the Cathedral; secondly, the pedestal painted in the background of the photograph is the Cross of Mañozca, which is in the atrium of the Cathedral; finally, the building in the background represents the Metropolitan Cathedral’s “Gate of Forgiveness.”

What importance could it have had that this character is photographed in that particular place? This photograph submits a symbolic struggle between liberal laicism and conservative religiosity, which is manifested in two symbols: the Judas (which is sold) and the Cathedral (where it is sold). In Mexico, Spanish missionaries began the custom of burning “Judas” during Holy Week during the colonial period. However, in the 19th century, in addition to its religious meaning, this practice had a lay meaning. The Judases came to represent different characters in public life that would be burned as a result of their actions, understood (like the actions of the original Judas by selling out Christ) as a betrayal of the people. Therefore, it could be understood that the ecclesiastical institution, represented by the Cathedral betrays the people, since it opposes liberal politics, and therefore, should be burned like a “Judas” in Holy Week.(13) It follows, then, that the intention of the aestheticizing view of the popular types and of Mexico City is not only artistic beautification but also the production of a social space aligned with liberal politics. Interestingly, this alignment of liberal politics tries to root itself in aesthetic policies about the popular classes—through which the photographic series analyzed here designs places, times, and relationships, redefining in this way the quotidian experience of Mexico City—that respond to the artifice of the studio and photographic technique, both of which are modernizing elements of art.(14)

Continuing with the topic of the production of social space, it should be mentioned that although the majority of the photographs try to place the scene in some urbanized area, the rural landscape does appear as an allegorical image of ruin. The backgrounds depicting the countryside can be divided into two types: houses and landscapes. The houses appear to be very fragile and humble, made of adobe and straw, with a precarious fence made of piled up stones and old tree branches. Examples of this are the photographs “El vendedor de guitarritas” (Image 10) and “El vendedor de pollos” (Image 11). Another important element is that all the rural characters are indigenous —unlike the majority of the urban characters who are mainly mestizos— and they also are barefoot, and dressed traditionally, that is, with clothes made out of cheap cotton fabric, and a straw hat. With these characters, the gaze abandons its aestheticizing intent and becomes realistic, like an archeologizing gaze. In this series, the city becomes the economic epicenter of the modern nation, while the countryside looms as something residual from the past, a backwards rural threat that borders on urban advance.

To analyze this topic more deeply, it is imperative to study “El Tlachiquero” (Image 5),(15) a photo that demonstrates certain particularities not found in other photos in the series. The first thing that stands out is that the tlachiquero is the only character in the series, urban or rural, that appears with his back turn to the viewer, in an extreme profile, with no identifiable face. He is, therefore, the only really anonymous character in the series. The tlachiquero is not a new vocation (like others that arose during the colonial period or later with the advent of more immigrants to the urban circuit). The technique of extraction of pulque remains the same as it was before the Spanish conquest. It is also a controlled vocation and the tlachiquero confined to a determined hacienda; therefore, he is not an errant subject, like the majority of those portrayed in the series. The tlachiquero’s vocation firmly connects him to a burgeoning industry even in the 19th century, the culture of pulque,(16) which is marginalized by moral questions.

To show the tlachiquero for the first time, Cruces and Campa prepared a special scene. They painted a majestic background with the two volcanoes that surround the Valley of Mexico, Popocatepetl and Iztlacihuatl. The image of these two volcanoes has been an indispensable element in the history of the representation of the Valley of Mexico. In colonial as well as modern painting, Popocatepetl and Iztlazihuatl refer to the pre-Hispanic past, to the glory days of the Aztec Empire, before the days of Spanish colonization. Furthermore, they created the ambiance of the study with straw, earth, bushes, dried branches, stones, and to complete the scene, they placed an authentic maguey at the center. Upon closely analyzing the image, we realize the person is not an actor, as could be thought of the model in the photographs “El vendedor de velas” and “El vendedor de Judas;” he is the real character who extracts aguamiel every day, betrayed by his callused bare feet. Finally, the person is not in a relaxed pose because he is doing his work extracting the aguamiel.

Solemn care was taken in creating the environment for the photo in the concern to go beyond a mere mimetic gesture in the selection and presentation of the tlachiquero. More than representation, the intent of the photograph was to take a slice of reality and demonstrate it. This person is unique in the series, which leads us to question why this portrait should stand out. Apart from being considered as something “authentically” Mexican—like the landscape that surrounds him—and in this way an inspiration for a romantic nationalistic and Mexican gaze, the aestheticizing gaze would appear to underline a nostalgic sentiment, lost and faceless in a geographic location that is being smothered by the advance of the City. But this nostalgic gaze is not trapped in wistful contemplation of the past, but rather, by being placed in a sequence of popular types, it would appear to be an attempt to locate this subject in one place: the mythical Mexican past, honored, but now left behind.

It is also important that after Cruces and Campa’s photograph of the tlachiquero, this character became the paragon of the Mexican popular type that paradoxically comes to be a person without a face, lost and anonymous. Cruces and Campa’s tlachiquero will be the icon of a disappearing culture. In time, different photographers have used the tlachiquero, seeking to exploit his plastic qualities.

However, the question remains as to why Cruces and Campa developed this aestheticizing gaze of popular types? Why did they not opt to portray them in their “natural environment”? In sum, what was the political angle behind this aesthetization? I will begin by emphasizing that, for the 19th century liberal bourgeoisie, the poverty in which three quarters of the population lived represented a moral problem more than a political problem. The generalized idea that existed about poverty proposed the existence of a series of “natural instincts” that made the poor predisposed to delinquency and crime.(17) For this reason, the criminal was identified by his condition, his clothing and social origin with the destitute, the unemployed, and the vagabonds. Within the liberal project, it would be necessary to change and punish the pernicious moral, the natural instincts that led the poor to crime, through education “to adjust their conduct; because it was necessary not to make them good owners, but good workers respectful of the property of others.”(18)

On the other hand, the mere existence of the lower classes was, in the eyes of the 19th century Mexican elite “contaminating, dirty, obscene, and perverted,”(19) and as such, an obstacle for the effectiveness of the modernizing project, of the success of the social order, and the recomposition of power. Words such as “disgusting,” “populacho,” or “horror,” used in the majority of chronicles and laws to refer to the poor, sustain the political discourse that offered the eradication of the problem through a pedagogical principle.(20) However, these expressions also betray fear of the appearance and threatening or simply offensive attitudes in the eyes of the bourgeoisie, conceived of in terms of the danger that the “other” could mean, that is, a different way of life, by option or tradition. Furthermore, the lepers, the vagrants, in sum, the popular people, infused fear because they contradicted the illusion of the original valley, of the ideal for which so many battles had been fought and, at the same time, challenge the reach of the bourgeois, liberal modernization project. In the end, in Olivier Debroise’s words:

the popular types represent a difficult to apprehend fraction of societies on the fringe of urbanization: those characters who still have not reached the ranks of citizenship, and are nevertheless indispensible for the good functioning of the urban area in its growth, the essential link between the inhabitant of the city, the “good people”, and the rest of the world.(21)

This was a society of the street and one in constant transformation. For this reason, it was necessary to apprehend it and make it into an image, identification as a control device. This exercise of recognition cannot be unlinked from the positivist thinking of the period, which postulated the registration of events as a complementary practice to observation, which corresponds to the first stage of scientific knowledge. This desire to register everything had already woken a collecting spirit that facilitated the apprehension of the diversity of things and species, including the human species. The collection and classification was necessary to standardize metonymic characteristics, selected for their important value, and, in this way, create easily recognized figures.

To achieve this, the aestheticizing gaze of Cruces and Campa sought, in the first place, to dispel that threatening character of the “otherness.” In their photographic series, they take it upon themselves to domesticate the “other,” put it in order with its dress, aspect, and attitude. This order fulfilled the modeling and pedagogical objective of good morals for the poor as well as sweetening a problematic image for the modern bourgeois to view. Furthermore, in this, a national project was constructed. As Enrique Florescano explains, “in the Mexican past there have been multiple memories, sustained by different ethnic groups, social sectors, political organizations, localities and regional entities that composed the country.”(22) The ordered, domesticated, and sweetened poor entered the project of national modernity, though in an assigned place. By “cleaning” the marginal sectors, the image of a place on the way to industrial and modern progress was reinforced.

On the other hand, the aestheticizing gaze locates the “other” in an acceptable place within Mexican identity—no longer outside of it—and, with this, it is able to sustain the necessary base for the traditional social hierarchy, even within modernity. In the same way, this “otherness” functioned, by accepted contradiction, as reinforcement for the very construction of the bourgeois Mexican identity. We should remember that this aestheticizing gaze was the bourgeois gaze reflecting back on itself—through the aesthetic lines of the bourgeois portrait—in this “other” which it cleaned, dressed, and located in an inverse place from its own.

In this inverse, self-reflexive reading, the 19th century Mexican bourgeois became keen on collecting the photographs of Cruces and Campa’s “Tipos populares” series. These characters began to successfully circulate in the cafés, in the grocery store, in the parlor of the bourgeois house, or in the display windows of photographic studios. In this way, once the series left the photographic studio it began to have a life of its own and fashioned an image of the country, both inside and outside Mexico. Inside Mexico, based on the aesthetics of consumption, images that designate different sectors of society are created and perpetuated. Everything is reduced to a cultural process of securing and validating “identities” in which the photographic portrait became the legitimating media of that world, where the material appearance of the person portrayed, as well as his or her attitude, define their belonging to social groups, to a city, and to a country.

Furthermore, exoticism stood out in the bourgeois collection of popular types. This exoticism began, of course, in the very taking of the image. From the beginning, photographers have been fascinated with the extremes of society: rich and poor exercise a fatal attraction for the lens. As Susan Sontag asserts, “from the beginning, professional photography symptomatically implied a kind of class tourism where the majority of the photographers combined glimpses of social abjection with portraits of celebrities.”(23) During almost two centuries, photographers have been drawn to misery to capture it and reproduce it. In the 19th century, photography seemed to have become the ideal medium to go out and hunt, fixate, dissect, and collect the exotic prey in a social safari. In this sense, the camera developed as a high caliber weapon to document a hidden reality. In the circulation and collection of the image, the exotic gaze of an “other” that is fierce, hunted, and possessed like a trophy for absolute scrutinizing contemplation.

Outside Mexico, several characters from this photographic series were even on exhibit in the Mexico pavilion in the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition in 1876. This exposition was the first international display in which Mexico participated, once the Republic was restored. Among others, Mexican president Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada perceived the Mexican participation in the word’s fairs as a place to “acquire international recognition for his regime.”(24) By selecting several of the photographs from Cruces and Campa’s series, consigned within the aesthetic language of bourgeois photography, the concordance between the realized image and liberal political thought was proven. As Walter Benjamin notes, “the universal expositions are the cusp of the capital aesthetic. They are an attempt for diversion by the working class and aim to enthrone the aesthetic of consumption.”(25) Probably by sending said photographs to the exposition, they sought to create a new image of Mexico’s popular sectors and demonstrate that, despite all the internal and external wars of strongmen and ephemeral empires, the country was on the path to modernization. Furthermore, while they had much in common with the caste paintings, with the selection of photos in the “Popular Types” series, the intention was to shed the image of the indigenous person degraded by centuries of Spanish domination, to show citizens that, even in poverty, lent a new face to the nation: hard working, clean, organized, and above all, part of modernity.

|

|

| Image 1. Author Francois Aubert, ca 1864 | Image 2. Author Cruces y Campa, ca 1868 |

|

|

| Image 3. Author Cruces y Campa, ca 1868 | Image 4. Author Cruces y Campa, ca 1868 |

|

|

| Image 5. Author Cruces y Campa, ca 1868 | Image 6. Author Cruces y Campa, ca 1868 |

|

|

| Image 7. Author Cruces y Campa, ca 1868 | Image 8. Author Cruces y Campa, ca 1868 |

|

|

| Image 9. Author Cruces y Campa, ca 1868 | Image 10. Author Cruces y Campa, ca 1868 |

|

|

| Image 11. Author Cruces y Campa, ca 1868 | |

Notes

1. Giséle Freund. La fotografía como documento social, 24.

2. Shelley E. Garrigan explains “[Mexican] Art critics began to refer to genre paintings as a base on which to construct a concept of community and collective identity, to calculate the nation’s level of aesthetic degradation or development, and to assess Mexico’s position with respect to modernity and status on the international scale.” Shelley E Garrigan. Collecting Mexico: museums, monuments, and the creation of national identity, 45.

3. The founding members of the studio, Antíoco Cruces and Luis Campa, inaugurated it in 1862. It stayed open until 1876, when Cruces and Campa separated. They used the photographic format “Carte de Visite”, patented by Adré A. Disderí in 1854. Each one of the portraits was made in the photographic technique Albume, and measured 4 ½ X 2 ½”. A complete study of this photographic studio is found in Patricia Massé Zendejas. Simulacro y elegancia en tarjetas de visita. Fotografías de Cruces y Campa (1998). For a study of the “Carte de Visit”, consult Elizabeth Anne McCauley. A. A. E. Disdéri and the Carte de Visite Portrait Photograph (1985).

4. Deborah Dorotinsky, “Los tipos sociales desde la austeridad del estudio,” focuses on popular types by French photographer Francois Aubert in its formal and stylistic composition; Patricia Massé Zendejas, Simulacro y elegancia en tarjetas de visita, is the most important study on Cruces and Campa studio under the bourgeois portrait guides, nevertheless the “Tipos Populares” series holds a marginal place in this author’s work. Roberto Tejada, National Camera, Andrea Noble Photography and Memory, and Leonardo Folgarait, Seen Mexico Photographed, focus on the visual culture following the Mexican Revolution. As Ignacio Sánchez Prado stetes “19th Century has been absence in the Mexican visual and cultural studies production.” Ignacio Sánchez Prado. “Estrategias para mirar la nación. El giro visual de los estudios culturales mexcianos en lengua inglesa.”In Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos. Vol. 27, No. 2. p 466.

5. Toward the middle of the 19th century Guillermo Prieto affirmed that the profile of the Mexican people barely began to become clear and for this reason is was necessary to construct a typology of it, “particularly of the abundant sector that was seen traipsing through the capital and whose different occupations demonstrate they are very diverse.” Guillermo Prieto. Apuntes históricos, 154.

6. André A. Disdéri. “Renseignements photographiques". París, 1855. McCauley, Elizabeth Anne. A. A. E. Disdéri and the Carte de Visite Portrait Photograph, 42.

7. Carlos Córdoba. Arqueología de la imagen, 22.

8. I understand the category of “social space” according to Henri Lefèbvre’s definition as the space produced within a determined economic, social, and political reality (for Lefèbvre, it would be the State). While Lefèbvre associated this social production of space with economic scaffolding, it also seems important to ascribe this spatial production to an imaginary that we symbolically constructed through different media, among them, photography, as I present it here. Henri Lefèbvre: “Social Space”. The Production of Space, 68-168.

9. For this, it is important to remember the chronicle of Madame Calderón de la Barca who narrates the scene in which she was involved at the time of writing a letter in a room of her house. In this chronicle, she comments how a sea of “lepers and rag tags” occupied the window to ask for alms, and after several attempts to divert her eyes, she ends up closing the curtains to escape the world of the ragged, avoid the visual confrontation, avoid looking or being seen.

10. During the 19th century the vagrancy laws, in force from 1835 and 1837, tried to control these establishments for being places that threatened the peace and good order. Alejandra Araya Espinoza. “De los límites de la modernidad a la subversión de la obscenidad: vagos, mendigos y populacho en México, 1821 – 1871.” Romana Falcón. Culturas de pobreza y resistencia: estudios de marginados, proscritos y descontentos, México 1804 – 1910, p. 80.

11. Manuel Antonio Carreño. Manual de urbanidad y buenas maneras… (1854), p. 41.

12. Judases are figures made of reed and paper that evoke the figure of Judas Iscariot and are to be burned on Holy Saturday.

13. It is important to mention that Mexican liberalism promoted laicism despite being labeled as atheistic by conservative groups.

14. I distinguish a fundamental difference between the political and policies, following Jacques Ranciere in terms of aesthetics: “there is an ‘aesthetics of politics’ […] the artistic practices take part in the partition of the perceptible insofar as they suspend the ordinary coordinates of sensory experience and reframe the network of relationships between spaces and times, subjects and objects, the common and the singular” (3); on the other hand, in acting in aesthetic policies, art acquires political power “insofar as it frames not only works or monuments, but also a specific space-time sensorium, as this sensorium defines ways of being together or being apart, of being inside or outside, in front of or in the middle of, etc.” (1-2). Jacques Ranciere: “The Politics of Aesthetics.” <http://theater.kein.org/node/99> January 20, 2007.

15. The tlachiquero is the one who extracts aguamiel from the maguey in order to make pulque.

16. The pulque area of the Valley of Mexico was a restricted area that went from the plains and followed the railroad lines to the pulque customs stations in Nonoalco and Pantaco in Mexico City and ended in the different pulquerías located throughout the city.

17. Salvador Rueda Smithers. El diablo de Semana Santa. El discurso político y el orden social en la Ciudad de México en 1850, p. 69. And, Torcuato S. Di Tella. “Las clases peligrosas a comienzos del siglo XIX en México.” Desarrollo económico, Vol 12, No 48 (Jan-Mar., 1973), pp 761-791.

18. Salvador Rueda Smithers. Idem. p. 60.

19. Alejandra Araya Espinoza. Op cit. p. 67.

20. Salvador Rueda Smithers. Op cit. p. 154.

21. Olivier Debroise. Fuga mexicana. Un recorrido por la fotografía en México, p. 154.

22. Enrique Florescano. Memoria mexicana, 549.

23. Susan Sontag. Sobre la fotografía, 68.

24. Mauricio Tenorio Trillo. Op cit. p 39.

25. Walter Benjamin. Iluminaciones II. Poesía y capitalismo, p. 179.

Works Cited

Araya Espinoza, Alejandra. “De los límites de la modernidad a la subversión de la obscenidad: vagos, mendigos y populacho en México, 1821 – 1871”. Romana Falcón. Culturas de pobreza y resistencia: estudios de marginados, proscritos y descontentos, México 1804 – 1910. México D. F: El Colegio de México, 2005.

Benjamin, Walter. Iluminaciones II. Poesía y capitalismo. Madrid: Taurus, 1998.

Burke, Peter. “El ‘descubrimiento’ de la cultura popular.” En Raphael Samuel, ed., Historia popular y teoría socialista. Barcelona: Crítica, 1984, p 78-92.

Carreño, Manuel Antonio. Manual de urbanidad y buenas maneras para uso de la juventud de ambos sexos; en el cual se encuentran las principales reglas de civilidad y etiqueta que deben observarse en las diversas situaciones sociales; precedido de un breve tratado sobre los deberes del hombre. Nueva York: D. Appleton & Cia, 1854.

Córdoba, Carlos. Arqueología de la imagen. Museo de historia mexicana, Monterrey, 2001.

Debroise, Olivier. Fuga mexicana. Un recorrido por la fotografía en México. México: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes (CONACULTA), 1998.

Di Tella. Torcuato S. “Las clases peligrosas a comienzos del siglo XIX en México”. Desarrollo económico, Vol 12, No 48 (Jan-Mar., 1973), pp 761-791.

Disdéri, André A. “Renseignements photographiques". París, 1855. In McCauley, Elizabeth Anne. A. A. E. Disdéri and the Carte de Visite Portrait Photograph. New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 1985.

Dorinsky, Deborah. “Los tipos sociales desde la austeridad del estudio”. Alquimia, 7- 21, México: (mayo - agosto 2004).

Florescano, Enrique. Memoria mexicana. Madrid: Taurus, 2001.

Folgarait, Leonardo. Seen Mexico Photographed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

Freund, Giséle. La fotografía como documento social. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 1993.

Garrigan, Shelley E. Collecting Mexico: museums, monuments, and the creation of national identity. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

Illades, Carlos. Nación sociedad y utopía en el romanticismo mexicano. México: Conaculta, Sello Bermejo, 2005.

Lefèbvre, Henri: “Social Space”. The Production of Space. Trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith. Oxford and Cambridge: Backwell, 1991.

Massé Zendejas, Patricia. Simulacro y elegancia en tarjetas de visita. Fotografías de Cruces y Campa. México: INAH, 1998.

Noble, Andrea. Photography and Memory in Mexico: Icons of Revolution. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2011.

Prieto, Guillermo. Apuntes históricos. México: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, 1999.

Ranciere, Jacques: “The Politics of Aesthetics”. <http://theater.kein.org/node/99> January 20, 2007.

Rueda Smithers, Salvador. El diablo de Semana Santa. El discurso político y el orden social en la Ciudad de México en 1850. México: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH), 199.

Sánchez Prado, Ignacio. “Estrategias para mirar la nación. El giro visual de los estudios culturales mexcianos en lengua inglesa.”En Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos. Vol. 27, No. 2, pp 449-469.

Sontag, Susan. Sobre la fotografía. Barcelona: Edhasa, 1996.

Tejada, Roberto. National Camera: Photography and Mexico’s Image Environment. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 2009.

Tenorio Trillo, Mauricio. Mexico at the World’s Fair: Crafting a Modern Nation. Berkeley-Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 1996.