Cinematic Ruinologies(1): Alamar and the Cuban Soviet Urban Imaginary in Contemporary Cuban Documentaries

Juan Carlos Rodríguez,The Georgia Institute of Technology

Many contemporary documentaries focusing on Cuban culture project Havana as the setting of the social changes, cultural dilemmas, and institutional conflicts in Post-Soviet Cuba. In contrast to sport, music, and biographic documentaries focusing on Havana’s iconic figures, other documentaries explore the social issues and urban challenges that have marked the history of the Cuban capital in the Post-Soviet period, including the housing crisis, the reorganization of urban routines in the mixed economy, and the emergence of new spaces and identities. In this essay, I will discuss some recent Cuban documentaries that explore the memories and spatial traces of the Soviet presence in Havana.

Many contemporary documentaries focusing on Cuban culture project Havana as the setting of the social changes, cultural dilemmas, and institutional conflicts in Post-Soviet Cuba. In contrast to sport, music, and biographic documentaries focusing on Havana’s iconic figures, other documentaries explore the social issues and urban challenges that have marked the history of the Cuban capital in the Post-Soviet period, including the housing crisis, the reorganization of urban routines in the mixed economy, and the emergence of new spaces and identities. In this essay, I will discuss some recent Cuban documentaries that explore the memories and spatial traces of the Soviet presence in Havana.

I view documentary as an audiovisual discourse that opens the possibility to examine urban imaginaries, which in turn reveal the ways city dwellers perceive, experience, and transform their cities.(2) Many documentaries offer ways of imagining the city that either overlap with or challenge some of the “mental mappings ” and “interpretive grids” developed by citizens, visitors, and tourist when exploring different urban realities.(3) Viewers can infer and reconstruct an imaginary map of the city each time a documentary gives shape to the navigation of the physical city and to the routes, itineraries, and actions of city dwellers. I would like to argue that documentaries are moving maps, cartographies on the move made with sequences of moving images that make visible the complex dynamics of urban flows.(4)

The cartographic function of documentary is a fundamental modality within a poetics of nonfiction film that derives from what Michael Renov has called “a documentary impulse”: “an outward gaze upon the world” (The Subject of Documentary 105). Renov’s own poetics of documentary includes four elements: “1. To record, reveal or preserve”; “2. To preserve or promote”; “3. To express”; “4. To analyze or interrogate” (The Subject of Documentary 74-85). My argument here is that any poetics of documentary will remain incomplete unless we add: “to map and navigate.” The analysis of how documentary’s formal and rhetorical strategies are used to map and navigate Havana highlights the role of media in the construction and transformation of Cuba’s urban landscapes and practices.

Various Cuban documentaries produced in the last decade have explored the deteriorated urban spaces that once served as emblems of the Soviet ideals of development in the island. These movies mark an important shift in the way Cuban documentaries approach questions of space in connection to issues associated with Soviet-sponsored development. In the 1970s, Cuban documentaries celebrating the technological progress of Havana’s port –under the tutelage of the Soviet Union– represented development as an expository argument involving a narrative of spatial transformation. In contrast, many Post-Soviet Cuban documentaries produced after the Special Period represented Cuban Soviet spaces in Havana as ruins framed within a narrative of disintegration. These spaces stand as local remainders that inspire poetic, testimonial, and essayistic explorations about the past, the present, and the future of the city and the nation. Some recent documentaries, like Ciudad del Futuro (Damián Bandín Carnero y Karin Losert, 2008) and Los bolos en Cuba y una eterna amistad (Enrique Colina, 2011), investigate the Soviet-inspired housing project of Alamar in East Havana. I would like to examine how these documentaries revisit the emblematic and now deteriorated Russian neighborhood in Alamar to interrogate the landscapes and social narratives of Havana that are associated with the Cuban Soviet urban imaginary.(5)

as emblems of the Soviet ideals of development in the island. These movies mark an important shift in the way Cuban documentaries approach questions of space in connection to issues associated with Soviet-sponsored development. In the 1970s, Cuban documentaries celebrating the technological progress of Havana’s port –under the tutelage of the Soviet Union– represented development as an expository argument involving a narrative of spatial transformation. In contrast, many Post-Soviet Cuban documentaries produced after the Special Period represented Cuban Soviet spaces in Havana as ruins framed within a narrative of disintegration. These spaces stand as local remainders that inspire poetic, testimonial, and essayistic explorations about the past, the present, and the future of the city and the nation. Some recent documentaries, like Ciudad del Futuro (Damián Bandín Carnero y Karin Losert, 2008) and Los bolos en Cuba y una eterna amistad (Enrique Colina, 2011), investigate the Soviet-inspired housing project of Alamar in East Havana. I would like to examine how these documentaries revisit the emblematic and now deteriorated Russian neighborhood in Alamar to interrogate the landscapes and social narratives of Havana that are associated with the Cuban Soviet urban imaginary.(5)

After the Special Period, Alamar has become an urban palimpsest. The neighborhood has played a prominent role in the critical examination of the Cuban Soviet past, particularly since it is considered a paradigm of Soviet-inspired urban development in the island. The multi-building housing complex was built with prefabricated materials in the 1970s by thousands of industrial and volunteer workers organized in mini brigades. The ideology behind this method of construction was to create a city for the new man, a city built by mini brigades organized around the principle of collective solidarity. For many Cubans, building and living in Alamar became synonymous with being committed to the revolution. But, as Velia Cecilia Bobes explains, Alamar also represented the monolithic and impersonal landscape of socialism: “Soviet Havana, with Alamar as its paradigmatic emblem, began to approach the principle of uniformity as the ideal of the city (constructive, spatial, and social), and the imaginary was articulated around the negation of social diversity via the representation of the socialist subject-the new man as its resident” (“Visit to a Non-Place: Havana and its Representations,” Havana Beyond the Ruins, Kindle book, loc. 381). The utopian aura of the mini brigade soon began to fade when it became clear that prefabricated materials and “people without any construction experience” was a bad mix (loc. 381). Mini brigade buildings were not simply mediocre in their construction but also designed to such a degree of uniformity that they lacked any aesthetic value. That explains why Cuban architect Mario Coyula, when praising Villa Panamericana, highlights the difference between this project of New Urbanism and “the chaos of Alamar” (“The Bitter Trinquennium and the Dystopian City”, Havana Beyond the Ruins, Kindle book, loc. 705).

In her text “Nostalgia,” Reina María Rodríguez evokes the complex layers of meaning that configure Alamar as an urban palimpsest through a series of questions: “And what remains of Alamar, the Eastern part of the city of Havana—“the city of the New Man,” also called “the last province of the USSR”? What remains of this zone where the Russians had their round-roofed houses, a zone then (and still) called their “little Russian beach,” with its prickly limestone outcrops and sea grapes, with an amphitheater and a trade around products later resold by many of the Russians to Cubans?” (Caviar with Rum, Kindle book, loc. 1215). I would like to argue that the rhetorical force of documentaries such as Ciudad del Futuro and Los bolos en Cuba comes from the ubi sunt motif implicit in Rodríguez questions. Even if the affective tonality of both documentaries flirts with nostalgia, it is clear that both movies create a multilayer emotional landscape that evokes the interplay of different affective responses to the dissolution of Cuban Soviet relations.

In Ciudad del Futuro, the images of Alamar and its children are juxtaposed to the voices of various adults that share memories about what it meant for them to grow up in Alamar in the 1970s. Weaving together the testimonies of different men and women, Ciudad del futuro explores Alamar’s changes from the perspective of some of its first residents, all of whom still live in the community today. The participants, none of whom appear on screen, nostalgically describe the enthusiasm and revolutionary commitment of the original residents of Alamar, but also reveal the challenges experienced by the residents during the Special Period. Some of them complain about the physical deterioration of the buildings, others express their grief after seeing many neighbors leaving Cuba during the balseros crisis. Still others observe with disenchantment the arrival of new residents whose lifestyles do not represent the revolutionary values of Alamar’s original residents. Most of them, however, declare their desire to stay in Alamar and never leave the community. The shared fidelity of these residents to Alamar, in spite of the changes experienced by the community, evokes the nostalgia for social uniformity as well as the desire to preserve the revolutionary values in spite of the threats that emerge today in Alamar’s socially diverse environment.

In Ciudad del Futuro, the images of Alamar and its children are juxtaposed to the voices of various adults that share memories about what it meant for them to grow up in Alamar in the 1970s. Weaving together the testimonies of different men and women, Ciudad del futuro explores Alamar’s changes from the perspective of some of its first residents, all of whom still live in the community today. The participants, none of whom appear on screen, nostalgically describe the enthusiasm and revolutionary commitment of the original residents of Alamar, but also reveal the challenges experienced by the residents during the Special Period. Some of them complain about the physical deterioration of the buildings, others express their grief after seeing many neighbors leaving Cuba during the balseros crisis. Still others observe with disenchantment the arrival of new residents whose lifestyles do not represent the revolutionary values of Alamar’s original residents. Most of them, however, declare their desire to stay in Alamar and never leave the community. The shared fidelity of these residents to Alamar, in spite of the changes experienced by the community, evokes the nostalgia for social uniformity as well as the desire to preserve the revolutionary values in spite of the threats that emerge today in Alamar’s socially diverse environment.

Only once does the documentary refer to Russians. The sequence begins with an aerial shot of the Russian’s round-roofed houses, followed by various shots of the houses façades, some of which are in ruins and others look as if they had been recently renovated. A woman in voiceover explains that the Russian community in Alamar was very reserved and did not mix with Cuban residents. Then, as the camera captures various kids playing in the street and eating gum in front of the round-roofed houses, two men in voiceover narrate that they used to trade coins for gum and caramel with Russian kids, at a time when eating gum was considered diversionismo, referring to ideological divergence. The sequence concludes with three shots of Cubans crossing in front of the Russian houses. A woman in voiceover recalls that Cubans could not disturb the foreigners in their zone, that Cubans could not enter the Russian zone. Then a man refers to the separation that existed between Cubans and Russians in Alamar as a psychological barrier: “You know that there were prohibitions. No police were there to stop you, but you know it was forbidden to go over there” (my translation). Behind Alamar’s apparent social and urban uniformity, Ciudad del Futuro reveals the divisions inside the city of the new man, those eroding from within the project of a classless society. Today’s freedom of movement, evidenced in the images of the people navigating the former Russian street, contrasts with the persistence of urban boundaries inscribed in the collective memory of the first residents of Alamar. While the testimonies bear witness to the internalization of social divisions in Alamar, the images of the former Russian street full of Cubans confirm that those boundaries have vanished after the Russians left Alamar.

bear witness to the internalization of social divisions in Alamar, the images of the former Russian street full of Cubans confirm that those boundaries have vanished after the Russians left Alamar.

When we analyze urban imaginaries in documentary, it is worth looking at the representations of the voice and human body. In Ciudad del futuro, the voiceover testimonies construct a mental and disembodied image of memory that suggests Cubans’ separation from Alamar’s Russian community. In contrast, Los bolos en Cuba combines archival footage with the situated testimony of Cuban poet Juan Carlos Flores, creating a cinematic and embodied image of memory of the Soviet presence in Havana.

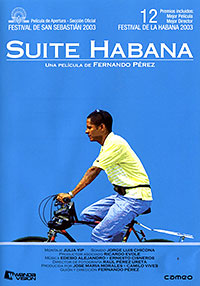

While Ciudad del Futuro is a documentary about Alamar that briefly evokes the Soviet presence, Los bolos en Cuba is a documentary entirely about the Soviet presence in the island that includes a five-minute sequence focusing on Alamar’s Russian neighborhood. Paying attention to this difference is important because it highlights the fact that Havana’s urban imaginaries in documentary are not exclusively represented in city symphony documentaries such as Suite Habana (Fernando Pérez, 2003) or El futuro es hoy (Sandra Gómez, 2009), both of which offer a panoramic view of the Cuban capital. In documentary, Havana’s urban imaginaries are represented in different formats and through various modes of representation. They come in different shapes and represent different spatial scales and arrangements; they can be found, for example, in movies focusing on local dynamics or national dilemmas.

The Alamar sequence in Enrique Colina’s Los bolos en Cuba begins with a piece of archival footage: a 1971 edition of the Noticiero ICAIC that shows Soviet leader Alexei Kosygin presenting a bust of Lenin to the best mini brigade of Cuban workers participating in the construction of Alamar. It continues with Juan Carlos Flores’s onscreen description of the Russian neighborhood and some shots of various Russian round-roofed houses, most of them abandoned and extremely deteriorated. Then Flores mentions the Alamar amphitheater, where residents used to watch Soviet war films, and the camera slowly pans through its ruins before offering a final wide shot of the amphitheater that ends dissolving into another piece of archival footage of a soviet war movie. Later, Flores reappears on the screen to explain the Cuban-Russian underground commerce, and the film cuts to an interview with a woman that explains the nature of these exchanges. The interview is followed by another piece of archival footage of a Cuban documentary exposing the development of the Port of Havana thanks to the Soviet collaboration with the Cuban authorities. The footage includes an interview with a soviet technician who proudly declares: “Here in the fishing port of Havana, there were 70 soviet comrades working, but now only three of us remain, because our Cuban comrades, our friends, have good work experience and can remain without our help.” In the context of the original interview “quedarse sin nuestra ayuda” (“remain without our help”) means that Cubans can do the job in the port by themselves. In the context of Los bolos en Cuba, however, this piece of archival footage from the 1970s operates in a twofold way: first, it reveals the arrogant and patronizing attitude of some Russian technocrats toward Cuban collaborators; and second, it can be interpreted as an involuntary prediction of the future, as an uncanny commentary that anticipates the dissolution Soviet Cuban relations in the 1990s, when Cuba in fact was hit by the loss of Soviet aid.

The Alamar sequence in Enrique Colina’s Los bolos en Cuba begins with a piece of archival footage: a 1971 edition of the Noticiero ICAIC that shows Soviet leader Alexei Kosygin presenting a bust of Lenin to the best mini brigade of Cuban workers participating in the construction of Alamar. It continues with Juan Carlos Flores’s onscreen description of the Russian neighborhood and some shots of various Russian round-roofed houses, most of them abandoned and extremely deteriorated. Then Flores mentions the Alamar amphitheater, where residents used to watch Soviet war films, and the camera slowly pans through its ruins before offering a final wide shot of the amphitheater that ends dissolving into another piece of archival footage of a soviet war movie. Later, Flores reappears on the screen to explain the Cuban-Russian underground commerce, and the film cuts to an interview with a woman that explains the nature of these exchanges. The interview is followed by another piece of archival footage of a Cuban documentary exposing the development of the Port of Havana thanks to the Soviet collaboration with the Cuban authorities. The footage includes an interview with a soviet technician who proudly declares: “Here in the fishing port of Havana, there were 70 soviet comrades working, but now only three of us remain, because our Cuban comrades, our friends, have good work experience and can remain without our help.” In the context of the original interview “quedarse sin nuestra ayuda” (“remain without our help”) means that Cubans can do the job in the port by themselves. In the context of Los bolos en Cuba, however, this piece of archival footage from the 1970s operates in a twofold way: first, it reveals the arrogant and patronizing attitude of some Russian technocrats toward Cuban collaborators; and second, it can be interpreted as an involuntary prediction of the future, as an uncanny commentary that anticipates the dissolution Soviet Cuban relations in the 1990s, when Cuba in fact was hit by the loss of Soviet aid.

The film then cuts to an interview with Flores and another woman in which she recalls a Russian kid named Tomás, the only Soviet child in their school. Flores reappears in the stage of the Alamar amphitheater by himself, wearing an Ushanka hat, and reading to the camera his poem “Mea Culpa por Tomás.” After Flores reads this poem about his envy of Tomás and his violent impulses against this Russian kid, the sequence ends with two testimonies. The woman accompanying the poet describes Tomás as a shy and introverted kid who probably felt lonely while living in Alamar. Flores, on the other hand, explains that many people used to speak publicly about the Cuban-Soviet friendship, but not many recognized the clashes and conflicts between Cubans and Russians resulting from the extreme differences between the two cultures. The sequence ends with a coda that serves as transition to the next sequence: another piece of archival footage of the Cuban celebration of the October Revolution in which the Soviet ambassador in Cuba cheers from a podium “Viva la amistad Cubano-soviética” (Long live the Cuban-Soviet friendship).

his violent impulses against this Russian kid, the sequence ends with two testimonies. The woman accompanying the poet describes Tomás as a shy and introverted kid who probably felt lonely while living in Alamar. Flores, on the other hand, explains that many people used to speak publicly about the Cuban-Soviet friendship, but not many recognized the clashes and conflicts between Cubans and Russians resulting from the extreme differences between the two cultures. The sequence ends with a coda that serves as transition to the next sequence: another piece of archival footage of the Cuban celebration of the October Revolution in which the Soviet ambassador in Cuba cheers from a podium “Viva la amistad Cubano-soviética” (Long live the Cuban-Soviet friendship).

Through the juxtaposition of archival footage and images of a cinema amphitheater in ruins, this sequence presents itself as a commentary of cinema’s role in the construction of the Cuban Soviet urban imaginary. The pieces of archival footage of Kosygin’s visit to Alamar and of the port reveal that the revolutionary transformation of Havana’s urban-scape involved construction plans and prefabricated materials, but these images also highlight Havana’s role as a cinematic city.(6) The cinematic urbanism of the Cuban revolution, as it appears in Los bolos en Cuba, is not a truth to be taken for granted but a representation of reality now under scrutiny, which confirms Michael Chanan point that “historical footage sometimes says more about the past of cinema and its way of seeing than it does about what it pictures” (The Politics of Documentary 257). As Chanan also explains, “documentaries quickly become dated, leaving the ideology which informed them looking threadbare” (257). What Los bolos en Cuba reveals is that the city of the new man was, among other things, a cinematic city, an ideological construction that served as the setting for the narration of Cuban Soviet achievements in urban development. By juxtaposing archival images of the past with images of the cinema amphitheater in ruins, Colina insinuates the ideological and material defeat of Alamar as a cinematic city.

As a cinematic city from the 1970’s that represented the goals and achievements of Cuban Soviet urbanism, Alamar emerged as a strategic projection within the cinematic urbanism of the Cuban revolution. Celebrating the human-technological convergence of mini brigade labor and prefabricated materials was part of a strategy based on the use value of cinema. The instrumental value of film has been characterized as an institutional endeavor that differs from a conception of cinema as public commercial entertainment. For Wasson and Acland, “cinema has also been useful, at times involved more with functionality than beauty” (“Introduction: Utility and Cinema,” Useful Cinema, 2). According to the authors:

[C]inema has long been implicated in a broad range of cultural and institutional functions, from transforming mass education to fortifying suburban domestic ideals. Schools, businesses, and public agencies invested in celluloid and its diverse family of technologies in order to instruct, to sell, and to make or remake citizens. In other words, cameras, films, and projectors have been taken up and deployed variously–beyond questions of art and entertainment–in order to satisfy organizational demands and objectives, that is, to do something in particular. (4)

Documentaries and newsreels offering a chronicle of the construction of Alamar participate in the project of useful cinema because they were the product of an institutional need to document urban transformation within the revolution. They served as tools to frame urban development as a revolutionary act. According to various ICAIC filmmakers who produced documentaries and newsreels about Alamar, they were able to exercise, up to a certain point, their creative freedom.(7) This, however, does not deny the fact that such nonfictional films are inscribed within a tradition of useful cinema implicit in ICAIC’s institutional role as co-producer, along with the Cuban Ministry of Construction, of a consolidated view of the revolution’s urban project.

Documentaries and newsreels offering a chronicle of the construction of Alamar participate in the project of useful cinema because they were the product of an institutional need to document urban transformation within the revolution. They served as tools to frame urban development as a revolutionary act. According to various ICAIC filmmakers who produced documentaries and newsreels about Alamar, they were able to exercise, up to a certain point, their creative freedom.(7) This, however, does not deny the fact that such nonfictional films are inscribed within a tradition of useful cinema implicit in ICAIC’s institutional role as co-producer, along with the Cuban Ministry of Construction, of a consolidated view of the revolution’s urban project.

Colina’s strategy in the Alamar sequence, in contrast, is to remix images of this useful cinema with images of ruins in order to challenge the use value of Alamar as a cinematic city. The sequence offers a critique of the Cuban revolution’s cinematic urbanism at two levels: at the level of film representation (Alamar as represented in these films) and at the level of screening practices (Alamar as a film exhibition venue). The sequence allegorically narrates the cinematic city’s transition from a mode of useful cinema at the service of the revolution to critical audiovisual practice that considers useful cinema as a ruin, a film culture that, to echo Hell and Schonle words, “seems to have lost its function or meaning in the present, while retaining a suggestive, unstable semantic potential” (“Introduction,” Ruins of Modernity 6). As a cinematic city, Alamar is now both a screen and urban failure. It evokes the defeat of a mode of seeing, the withering of a utopian gaze, and the disappearance of an audience that used to imagine itself as enacting a socialist citizenship while transforming the city on and off the screen.

In the documentary Havana: New Art of Making Ruins, Antonio José Ponte argues that Havana’s ruins serve to simulate the devastating consequences of a war that did not take place, that of the US against Cuba. In way that resembles Ponte’s vision of ruins, both Colina and Flores link Alamar’s ruinous film amphitheater with Soviet war cinema, evoking another virtual war that did not take place. The ruin of cinema in Los bolos en Cuba recalls a virtual war that primarily took place in Cuban screen culture: the invasion of Cuban screens by Soviet war films, the bombing of Cuban audiences with images of Soviet military victories. The documentary insinuates that the screening of Soviet war cinema in Cuba involved not only the projection of Soviet imperialist desires but also of Cuban colonial anxieties. At various points, Los bolos en Cuba makes us aware that some Cubans experienced the Soviet presence in the island almost as an episode of cultural imperialism. When the image of the amphitheater in ruins dissolves into a piece of archival footage of a Soviet war film, Colina creates a false yet poetic link between the destruction of the amphitheater and the war on screen. The association of images seems to suggest two things: first, that the projection of Soviet war films may have been used to intimidate Cuban audiences (it is not clear whether the strategy came from Moscow or from Havana); and second, that Soviet ideological indoctrination contributed to the destruction of some cultural spaces in revolutionary Cuba. Additionally, this piece of archival footage full of Soviet soldiers is a phantasmagoric image that also bears witness to a model of social reproduction heavily dependent on the militarization of Cuban citizens. Through this image, the documentary allows for the return of the Soviet ghosts that are still haunting the Cuban political imagination. When connected to the fictional and nonfictional archival images, the film amphitheater in ruins highlights the vacuity of meaning haunting Alamar as a cinematic city, but also the proliferation of meanings made possible by an audiovisual practice that is aware of taking the shape of a cinematic ruinology.

war that did not take place. The ruin of cinema in Los bolos en Cuba recalls a virtual war that primarily took place in Cuban screen culture: the invasion of Cuban screens by Soviet war films, the bombing of Cuban audiences with images of Soviet military victories. The documentary insinuates that the screening of Soviet war cinema in Cuba involved not only the projection of Soviet imperialist desires but also of Cuban colonial anxieties. At various points, Los bolos en Cuba makes us aware that some Cubans experienced the Soviet presence in the island almost as an episode of cultural imperialism. When the image of the amphitheater in ruins dissolves into a piece of archival footage of a Soviet war film, Colina creates a false yet poetic link between the destruction of the amphitheater and the war on screen. The association of images seems to suggest two things: first, that the projection of Soviet war films may have been used to intimidate Cuban audiences (it is not clear whether the strategy came from Moscow or from Havana); and second, that Soviet ideological indoctrination contributed to the destruction of some cultural spaces in revolutionary Cuba. Additionally, this piece of archival footage full of Soviet soldiers is a phantasmagoric image that also bears witness to a model of social reproduction heavily dependent on the militarization of Cuban citizens. Through this image, the documentary allows for the return of the Soviet ghosts that are still haunting the Cuban political imagination. When connected to the fictional and nonfictional archival images, the film amphitheater in ruins highlights the vacuity of meaning haunting Alamar as a cinematic city, but also the proliferation of meanings made possible by an audiovisual practice that is aware of taking the shape of a cinematic ruinology.

In Los bolos en Cuba, Cuban poet Juan Carlos Flores, who grew up and still lived in Alamar at the time of the film production, offers a situated testimony in which he describes the Russian neighborhood. His situated testimony provides an embodied image of memory that differs from the disembodied image of memory created by the voices of Alamar’s residents interviewed in Ciudad del Futuro. His situated testimony is complemented by the performance of his poem Mea culpa por Tomás in the amphitheater’s ruins, which functions as a supplementary testimonial layer that displays the other side of the virtual war, the real conflicts between Cubans and Russians. The inclusion of Flores’s poem in Los bolos en Cuba serves to  put into question the cinematic display of the Cuban Soviet solidarity in Cuban newsreels.

put into question the cinematic display of the Cuban Soviet solidarity in Cuban newsreels.

For Jacqueline Loss, “the pain and beauty of Flores’s poetry is without the comedic relief” (Dreaming in Russian 158). I would like to argue, however, that Flores’s use of an Ushanka (a Russian military winter hat) is a comic element in tension with the pain for the loss of the collective. In Flores’s performance for Colina’s camera, anger, frustration, and nostalgia are intermittently clashing with humor, a layer of meaning deriving from the clownish touch of an Ushanka hat as it is used in the tropics. The out of context use of the Ushanka is a ridiculous element that highlights the absurd adoption of some Russian cultural traces in Cuba, but it also hints at both the heated conflicts and cold relations between Cubans and Russians, as those described by Flores in his poem. As Flores finishes his poem, we see a close up of the poet’s face that transform itself into a pan shot revealing the empty and ruinous benches of the amphitheater. At the end of his performance, Flores appears facing the empty benches of the amphitheater in ruins as if suggesting the vanishing of the nosotros (we) repeated in his poem. Read from the stage of an amphitheater in ruins, Flores’s poem not only represents the ruins of the collective but also theatrical or performative failure of the Cuban Soviet solidarity. Additionally, the sequence implies that a subject emerges from the ruins of the collective, from the ruins of a false theatricality, to express his pain and affirm his creative freedom. By adding new meanings to the literary text, the cinematic performance of the poem highlights the role of documentary in the reshaping of the Cuban Soviet imaginary.

of the collective, from the ruins of a false theatricality, to express his pain and affirm his creative freedom. By adding new meanings to the literary text, the cinematic performance of the poem highlights the role of documentary in the reshaping of the Cuban Soviet imaginary.

The allusion to a virtual war and Flores’s performance invite us to consider that the gaze cast upon the ruins of Alamar in Los bolos en Cuba could be interpreted as an adaptation or reworking of the gaze cast upon the ruins of Centro Havana by Antonio José Ponte in Havana: New Art of Making Ruins. According to Hell and Schonle, “each new ruination” is an eye-opening experience that “claims to offer a privileged conduit to reality” and produces “the feeling of abrupt awakening” (Ruins of Modernity, 6). In order to conclude, one could say that documentaries about republican ruins such as Havana: New Art of Making Ruins create a sense of awakening regarding the abandonment of Havana by revolutionary authorities. In contrast, documentaries about Soviet ruins such as Los bolos en Cuba transmit “the feeling of abrupt awakening” by revealing the gaps, mistakes, and conflicts that have led to the premature deterioration of Havana’s socialist and utopian landscapes.

Notes

1. The title comes from a book project I am currently developing: Cinematic Ruinologies: Cuba, Documentary and the Ambiguous Rhetoric of Decay. In the first part of this project, I analyze various documentaries on ruins made by Cuban and international filmmakers after the Special Period in order to understand the role of documentary as ruinology. In the second part of the project, I investigate the consequences of the biodeterioration of Cuban films archived in ICAIC (the Cuban Film Institute) to highlight that performing film archival research in the 21st century, in the age of digital technologies, is another form of ruinology. The ideas of this essay were presented at two conferences: at the ACLA 2014 conference in New York, as part of a panel entitled “(Un)concecrating Havana,” organized by Cesar Salgado and Juan Pablo Lupi, and the LASA 2014 conference in Chicago, as part of a panel entitled Development, Dependency and Beyond, organized by Isis Sadek and Justin Read. I would like to thank panel organizers and participants for their feedback. I appreciate Cesar Salgado, Isis Sadek, Jaqueline Loss, and Jossianna Arroyo’s for their feedback during the discussion session. I would also like to thank the EthnoCuba Facebook network, and its organizer Ariana Hernández-Reguant, for reading my work on urban imaginaries from Cuba in documentary. Their objections and suggestions to my work have helped me reconsider some initial positions on the subject and have also motivated some key changes that I consider have improved my argument. Special thanks go to Walfrido Dorta and Ernesto Menendez Conde for reading and commenting my previous work on urban imaginaries. This work also comes from a long dialogue with Francisco Morán, Marc Zimmerman, Michael Chanan, Jorge Luis Sánchez, Julio Ramos, Luciano Castillo, Anastasia Valecce, Ruth Goldberg, José Quiroga, and Rafael Rojas. I am very grateful of this ongoing conversation. Last but not least, I would like to thank my research assistant Ernesto Sánchez Valdés for his critical wisdom and exceptional support during my time in Havana.

2. For Andreas Huyssen, urban imaginaries refer to “the way city dwellers imagine their own city” (Other Cities, Other Worlds: Urban Imaginaries in a Globalizing Age 3). In Huyssen’s view, they constitute the “cognitive and somatic image which we carry within us of the places where we live, work and play. It is an embodied material fact ” (3). “What we think about a city and how we perceive it,” Huyssen argues “informs the ways we act in it” (3).

3. Edward Soja defines urban imaginary as the “mental or cognitive mappings of urban reality and the interpretive grids through which we think about, experience, evaluate, and decide to act in the places, spaces and communities in which we live” (Postmetropolis 324). For Armando Silva, however, urban imaginaries include also the perspectives of city visitors, neighbors from near-by cities and tourists. See also Silva’s Imaginarios urbanos (2006).

4. Michael Chanan describes the cartographic impulse of documentary in his book The Politics of Documentary: “documentary creates its own cognitive map of the world it goes out to meet. Like all cognitive maps, the places are real but the angles

from which they’re seen and the ways of moving around between them derive from the map-maker’s own criteria—cultural, social, imaginary and symbolic” (78).

5. My essay is part of an effort to understand the persistence of Soviet relics and cultural references in Cuban cultural production. It is in dialogue with others works on the subject: Damaris Puñales Alpizar’s Escrito en Cirílico: el ideal post-soviético en la cultura cubana posnoventa (Editorial Cuarto Propio, 2012); Jaqueline Loss’s edited collection Caviar with Rum: Cuba-USSR and the Post-Soviet Experience (Palgrave, 2012) and also Loss’s more recent book book Dreaming in Russian: The Cuban Soviet Imaginary (U of Texas P, 2013).

6. My research is in dialogue with many studies focusing on the relatioship between cinema and the city: Cinema & Architecture : Méliès, Mallet-Stevens, Multimedia, editado por François Penz y Maureen (Londres: BFI, 1997); The Cinematic City, editado por David B. Clarke (Londres y Nueva York: Routledge, 1997); Cinema and the City: Film and Societies in a Global Context, editado por Mark Shiel y Tony Fitzmaurice (Oxford, UK y Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Publishers, 2001); Donald James, Imagining the Modern City, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999); Katherine Shonfield, Walls Have Feelings: Architecture, Film and the City (Londres y Nueva York: Routledge, 2000); Stephen Barber, Projected Cities (Londres: Reaktion Books, 2002); Giuliana Bruno, Atlas of Emotion : Journeys in Art, Architecture, and Film (Londres y Nueva York: Verso, 2002); Global Cities : Cinema, Architecture, and Urbanism in a Digital Age, editado por Linda Krause y Patrice Petro (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2003); Paula J. Massood, Black City Cinema : African American Urban Experiences in Film (Philadelphia : Temple University Press, 2003); Ewa Mazierska, From Moscow to Madrid : Postmodern Cities, European Cinema (Londres: I.B. Tauris, 2003; Screening the City, editado por Mark Shiel y Tony Fitzmaurice (Londres y Nueva York: Verso, 2003); Mark Shiel, Italian Neorealism : Rebuilding the Cinematic City (Londres y Nueva York: Wallflower Press, 2006); Nezar Al Sayyad, Cinematic Urbanism : a History of the Modern City from Reel to Real (Londres y Nueva York: Routledge, 2006); Charlotte Brunsdon, London in Cinema : the Cinematic City since 1945 (Londres: BFI, 2007); City that Never Sleeps : New York and the Filmic Imagination, editado por Murray Pomerance (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2007); The Urban Generation : Chinese Cinema and Society at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century, editado por Zhang Zhen (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007); Ranjani Mazumdar, Bombay Cinema : an Archive of the City (Minneapolis : University of Minnesota Press, 2007); Cities in Transition: the Moving Image and the Modern Metropolis, editado por Andrew Webber y Emma Wilson (Londres: Wallflower, 2008); Barbara Mennel, Cities and Cinema (Londres y Nueva York: Routledge, 2008); La ciudad en la literatura y el cine : aspectos de la representación de la ciudad en la producción literaria y cinematográfica en español, editado por Joan Torres-Pou y Santiago Juan-Navarro (Barcelona : PPU, 2009); Yomi Braester, Painting the City Red: Chinese Cinema and the Urban Contract (Durham y Nueva York: Duke University Press, 2010); Cinema at the City's Edge : Film and Urban Networks in East Asia, editado por Yomi Braester y James Tweedie (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2010); The City and the Moving Image: Urban Projections, editado por Richard Koeck y Les Roberts (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010); Urban Images: Unruly Desires in Film and Architecture, editado por Synne Bull y Marit Paasche (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2011); Urban Cinematics: Understanding Urban Phenomena through the Moving Image, editado por François Penz y Andong Lu (Bristol y Chicago: Intellect, 2011); Richard Koeck, Cine-scapes: Cinematic Spaces in Architecture and Cities (Londres y Nueva York: Routledge, 2013).

7. Fernando Pérez, director of Cascos blancos (1975), a documentary about mini brigades filmed in Alamar, explained to me in an interview that most of the time the topics of this kind of documentaries where assigned to the film directors (“eran por encargo”) according to institutional needs in a particular moment. Cascos blancos, for example, was produced for a housing conference in Canada. Directors, Pérez argued, could always reject an assignment in case they were not interested. Pérez also clarified that, aside from the thematic constrains, ICAIC directors had a high degree of creative freedom when producing housing or other documentaries. Other housing documentaries filmed in Alamar, like Microbrigadas: Un Diario by Héctor Veitía, were produced by the personal initiative of the ICAIC film director. In an interview, Veitía explained to me that he was inspired to make a documentary about mini brigade workers after reading a diary written by a worker that was recommended to him by a friend.

Works cited

Bobes, Velia Cecilia. “Visit to a Non-Place: Havana and its Representations,” Havana Beyond the Ruins: Cultural Mapping after 1989. Durham: Duke UP, 2011. Kindle Book.

Chanan, Michael. The Politics of Documentary. London: BFI, 2007.

Coyula, Mario. “The Bitter Trinquennium and the Dystopian City,” Havana Beyond the Ruins: Cultural Mapping after 1989. Durham: Duke UP, 2011. Kindle Book.

Hell, Julia and Schönle, Andreas. “Introduction,” Ruins of Modernity. Durham: Duke UP, 2010.

Andreas Huyssen Other Cities, Other Worlds: Urban Imaginaries in a Globalizing Age

Loss, Jaqueline. Caviar with Rum: Cuba-USSR and the Post-Soviet Experience. New York:Palgrave, 2012.

---. Dreaming in Russian: The Cuban Soviet Imaginary. Austin, TX: U of Texas P, 2013.

Puñales Alpizar, Damaris. Escrito en Cirílico: el ideal post-soviético en la cultura cubana posnoventa. Santiago de Chile: Editorial Cuarto Propio, 2012.

Renov, Michael. The Subject of Documentary. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2004.

Rodríguez, Juan Carlos. “Interview with Fernando Pérez,” Unpublished manuscript, December, 2014.

---. “Interview with Héctor Veitía,” Unpublished manuscript, November, 2014.

Rodríguez, Reina María. “Nostalgia” Caviar with Rum: Cuba-USSR and the Post-Soviet Experience. New York: Palgrave, 2013.Kindle Book.

Silva, Armando. Imaginarios Urbanos. Bogotá: Arango, 2006.

Edward Soja Postmetropolis: Critical Studies of Cities and Regions. London: Wiley-Blackwell, 2000.

Wasson, Haidee and Acland, Charles R.. “Introduction: Utility and Cinema,” Useful Cinema. Ed. Charles R. Acland and Haidee Wasson. Durham: Duke UP, 2011.