San Cristóbal de La Habana

Joseph Hergesheimer

(excerpts)

As, in a temporary stoppage of its circular traffic, I walked across the Parque Central, its limits seemed to extend indefinitely, as if it had become a Sahara of pavement exposed to the white core of the sun; and I passed with a feeling of immense relief into the shade of a book-shop at the head of Obispo Street, where the intolerable glare slowly faded from my vision as I fingered the heaps of volumes paper-bound in a variegated brightness of color and design. In any book-shop I was entirely at home, contented; and here specially I was prepossessed with the idea of buying a great number of the novels solely for their covers—in short, making a collection of Spanish pictorial bindings. But the novels, I discovered, were, even in paper, almost a peso each; and since I was reluctant to invest two hundred or more dollars in a mere beginning, the idea vanished. Their imaginative quality, however, the drawing and color printing, were excellent, far better than ours; in fact, we owned nothing at all like them.

As, in a temporary stoppage of its circular traffic, I walked across the Parque Central, its limits seemed to extend indefinitely, as if it had become a Sahara of pavement exposed to the white core of the sun; and I passed with a feeling of immense relief into the shade of a book-shop at the head of Obispo Street, where the intolerable glare slowly faded from my vision as I fingered the heaps of volumes paper-bound in a variegated brightness of color and design. In any book-shop I was entirely at home, contented; and here specially I was prepossessed with the idea of buying a great number of the novels solely for their covers—in short, making a collection of Spanish pictorial bindings. But the novels, I discovered, were, even in paper, almost a peso each; and since I was reluctant to invest two hundred or more dollars in a mere beginning, the idea vanished. Their imaginative quality, however, the drawing and color printing, were excellent, far better than ours; in fact, we owned nothing at all like them.

They had a freedom of cruelty, a brutality of statement, of truth, absent in American sentimentality: where women were without clothes they were naked, anatomically accounted for, as were the men; and the symbolical representations of labor and injustice were instinct with blood and anguish. A surprising number of stories by Blasco Ibañez were evident; and it struck me that if I had read him in those casual bright copies, without the ponderous weight of his American volumes and uncritical reputation, I might have found a degree of enjoyment. There were a great many magazines, mostly Spanish, gayly covered but with the stupidest contents imaginable—the bad reproductions of contemporary photographs on vile grey paper; although one, La Esefa, admirably reproduced, in vivid color and titles, the Iberian spirit of the lighter Goya.

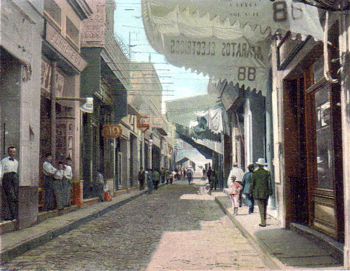

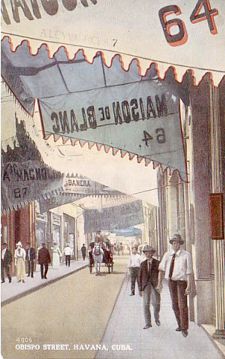

Though I had been on narrow streets before, I had never seen one with the dramatic quality of Obispo. Hands might almost have touched across its paved way, and the sidewalks, no more than amplified curbs, hardly allowed for the width of a skirt. It was cooled by shadow, except for a narrow brilliant strip, and the open shops were like caverns. The windows were particularly notable, for they held the wealth, the choice, of what was offered within: diamonds and Panama hats, tortoise shell, Canary Island embroidery, and perfumery. There were cafes that specialized in minute cakes of chocolate and citron and almond paste set out in rows of surprisingly delicate workmanship, and shallow cafes whose shelves were banked with cordials and rons, gin, whiskies, and wine. There were bottles of eccentric shape holding divinely colored liqueurs, squat bottles and pinched, files of amber sauternes, miniature glass bears from Russia filled with Kummel, yellow and green chartreuse, syrupy green and white menthes, the Cinziano vermouth of Italy, Spanish cider, and orderly companies of mineral waters.

almost have touched across its paved way, and the sidewalks, no more than amplified curbs, hardly allowed for the width of a skirt. It was cooled by shadow, except for a narrow brilliant strip, and the open shops were like caverns. The windows were particularly notable, for they held the wealth, the choice, of what was offered within: diamonds and Panama hats, tortoise shell, Canary Island embroidery, and perfumery. There were cafes that specialized in minute cakes of chocolate and citron and almond paste set out in rows of surprisingly delicate workmanship, and shallow cafes whose shelves were banked with cordials and rons, gin, whiskies, and wine. There were bottles of eccentric shape holding divinely colored liqueurs, squat bottles and pinched, files of amber sauternes, miniature glass bears from Russia filled with Kummel, yellow and green chartreuse, syrupy green and white menthes, the Cinziano vermouth of Italy, Spanish cider, and orderly companies of mineral waters.

These stores had little zinc-topped bars, and there were always groups of men sipping and conversing in their rapid intent manner. The street was crowded and, invariably allowing the women the wall, it was necessary to step again and again from the sidewalk. They were mostly Americans: the Cuban women abroad were in glittering automobiles, already elaborate in lace and jewels and dipping hats, and drenched in powder. They were, occasionally, when young, extremely beautiful, with a dark haughtiness that I had always found irresistible.

In my early impressionable years it had continually been my fate to be entranced by lovely disagreeable girls with cloudy black hair and skin stained with brown rather than pink. Imperious girls with elevated chins and straight sensitive noses! They had never, by any chance, paid the slightest attention to me; and the Cubans passing by with an air of supreme disdain called back my old interest and my old desire. I felt, for the moment, very young again and capable of romantic folly, of following a particular beauty to where her motor—a De Dion Landaulet—disappeared into a courtyard with the closing of the great iron-bound doors.

In my early impressionable years it had continually been my fate to be entranced by lovely disagreeable girls with cloudy black hair and skin stained with brown rather than pink. Imperious girls with elevated chins and straight sensitive noses! They had never, by any chance, paid the slightest attention to me; and the Cubans passing by with an air of supreme disdain called back my old interest and my old desire. I felt, for the moment, very young again and capable of romantic folly, of following a particular beauty to where her motor—a De Dion Landaulet—disappeared into a courtyard with the closing of the great iron-bound doors.

A marked, not to say sensational, transformation of my own person had been a conspicuous part of that young imaginary business; for, though I was fat and clumsy, I managed to see myself tall and engaging, and dark, too; or, anyhow, a figure to beguile a charming girl. Something of that hopeless process had taken place in me once more, now the vainer for the fact that even my youth had gone. The quality which called back a past illusion was very positive in Havana, and my feeling for the city was greatly enriched, further defined. It was charged with hazard for what men like me had dreamed, leaving the actuality for the pretended; the pretended, that so easily became the false, was, in Havana, real.

The Obispo under its striped awnings, with its merchandise of coral and high combs and pineapple cloths; the women magnetic with a Spain that had slept with the East, the South; the bright blank walls, lemon yellow, blue, rose; the palms borne against the sky on trunks like dulled pewter; the palpable sense of withdrawn dark mystery, all created an atmosphere of a too potent

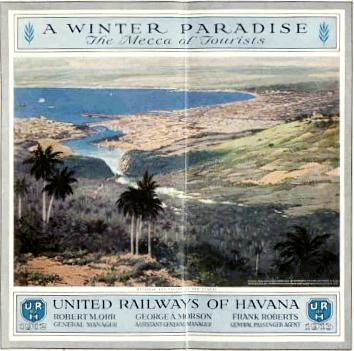

magnetic with a Spain that had slept with the East, the South; the bright blank walls, lemon yellow, blue, rose; the palms borne against the sky on trunks like dulled pewter; the palpable sense of withdrawn dark mystery, all created an atmosphere of a too potent  seductiveness. The street ended in the Plaza de Armas, with the ultramarine sea beyond; and as I sat, facing the arched low buff façade of the President's Palace, my brain was filled with vivid fragments of emotion.

seductiveness. The street ended in the Plaza de Armas, with the ultramarine sea beyond; and as I sat, facing the arched low buff façade of the President's Palace, my brain was filled with vivid fragments of emotion.

What suddenly I realized about Havana, the particular triumph of its miraculous vitality, was that it had never, like so much of Italy, degenerated into a museum of the past, it was not in any aspect mortuary. Its relics of the conquistadores were swept over by the flood of to-day. Yet I began to be vaguely conscious of the history of Cuba, of that Cuba from which Cortez had set sail, in the winter of fifteen hundred and nineteen, for Mexico. Later this would, perhaps, become clearer to me; not pedantically, but because the spirit of that early time was still alive. I made no effort to direct my mind into deep channels. What must come must come; and if it were a gin rickey rather than the slavery of the repartimento system, I'd be little enough disturbed.

The gin rickey proved to be an immediate reality, in the patio of the Inglaterra—a stream of silver bubbles shot into a glass where an emerald lime floated vivaciously. I had no intention of going out again until the shadows of the late afternoon had lengthened far toward the white front of the Gomez-Mena building across the plaza; and after lunch I went up to the quiet of my room. I should, certainly, write no letters, read—idly —none of the few books published about Cuba, which were on my table; and I began the essays of James Huneker called Bedouins. His rhapsodies over Mary Garden, as colorful in style as the glass above the window, I soon dropped and picked indifferently among the novels that remained. A poor lot —the thin current stream of American fiction, doubly pale in Havana.

The gin rickey proved to be an immediate reality, in the patio of the Inglaterra—a stream of silver bubbles shot into a glass where an emerald lime floated vivaciously. I had no intention of going out again until the shadows of the late afternoon had lengthened far toward the white front of the Gomez-Mena building across the plaza; and after lunch I went up to the quiet of my room. I should, certainly, write no letters, read—idly —none of the few books published about Cuba, which were on my table; and I began the essays of James Huneker called Bedouins. His rhapsodies over Mary Garden, as colorful in style as the glass above the window, I soon dropped and picked indifferently among the novels that remained. A poor lot —the thin current stream of American fiction, doubly pale in Havana.

The day wheeled from south to west. I was perfectly contented to linger doing nothing, scarcely thinking, in the subdued and darkened heat. There was a heavy passage of trunks through the echoing hall without, the melancholy calling of the evening papers rose on the air; I was enveloped in the isolation of a strange tongue. To sit as still as possible, as receptive as possible, to stroll aimlessly, watch indiscriminately, was the secret of conduct in my situation. Nothing could be planned or provided for. The thing was to get enjoyment from what I did and saw; what benefit I should receive, I knew from long experience, would be largely subconscious. I had been in Havana scarcely more than a day, and already I had collected a hundred impressions and measureless pleasure. How wise I had been to come . . . extravagantly, with— as it were—a flower in my coat, a gesture of protest, of indifference, to all that the world now emphasized.

p. 48 – 56

[...]

There was some question of where I'd go for dinner, for in Havana there were many cafes to explore—the Dos Hermanos, the Paris, the Florida, the Hotel de Luz, the Miramar; but, finally, I walked down to the Prado, to the sea and the Miramar, a little because of its situation, directly on the Malecon, but principally for the reason that it had one of the most beautiful names possible, a name which called up the image of a level tide so smooth that it held in shining replica the forts, the ships, and the clouds. Tables were prepared for dinner in the restaurant, while those on the terrace were without cloths; but there I determined to sit, and the waiter whose attention I captured, after a long delay, agreed.

Miramar, a little because of its situation, directly on the Malecon, but principally for the reason that it had one of the most beautiful names possible, a name which called up the image of a level tide so smooth that it held in shining replica the forts, the ships, and the clouds. Tables were prepared for dinner in the restaurant, while those on the terrace were without cloths; but there I determined to sit, and the waiter whose attention I captured, after a long delay, agreed.

A solitary couple had their heads together by the window, and they, with myself, were the only diners. It was, evidently, not now the place to go to at this hour. Beyond the dining-room, a patio, or rather an open court, was set for dancing, melancholy as such spaces can be, deserted and half-lighted; but I saw that a considerable activity was expected much later.

I was glad that the terrace was empty, for, with the light now faded from the sea and its blueness merging into black, the remote tranquillity of evening was happier without a sharp chatter of  voices. The Miramar, considering its place—the most advantageous in all Havana—and fame was surprisingly small: scarcely more than two stories high, the sombre maroon walls with their long windows hardly filled an angle of the Malecon. The dinner was slow in arriving, the silver made its appearance, a goblet was brought separately, a plate of French bread was later followed by its butter. The minute native oysters were no more than shreds adhering to their shells, but they had a notable flavor; a crawfish was at its brightest apogee; and an omelet browned in a delicate perfection of powdered sugar.

voices. The Miramar, considering its place—the most advantageous in all Havana—and fame was surprisingly small: scarcely more than two stories high, the sombre maroon walls with their long windows hardly filled an angle of the Malecon. The dinner was slow in arriving, the silver made its appearance, a goblet was brought separately, a plate of French bread was later followed by its butter. The minute native oysters were no more than shreds adhering to their shells, but they had a notable flavor; a crawfish was at its brightest apogee; and an omelet browned in a delicate perfection of powdered sugar.

I deserted Spanish wine, the admirable Riscal, for champagne; for there was about an air of departed charm, the whisper of old waltzes and tarleton, that demanded commemoration. The Miramar had been the gay center of that mid-century life which had folded Havana in the lasting influence of its memories. A gaiety not even at a disadvantage compared to the feverish society of today! The bodices then had been no more than scraps of chambery gauze and Chinese ribbon below shoulders to the whiteness of which the entire feminine age had been devoted. The flounced bell skirts had swung airily on gracious silk clappers.

The automobiles on the Malecon multiplied, for the night was hot; soon there was a solid double opposed procession on the broad sweeping drive. This was a triumph of American engineering and, I had no doubt, an improvement on the informality of rocks and debris that had existed before. Yet I should liked to have seen it when the promenade had not yet been laid down with mechanical precision, in, perhaps, the early seventies. Then there were sea baths cut in the live rock at the end of the Paseo Isabel, at the Campos Eliseos, where the water was like a cooler liquid green air, and where, after storms, a foaming surf poured over the barriers. There were no motors then, but volantes and the modern quintrins[sic], with two horses, one outside the shafts, and a riding calesero in vermilion and gold lace; and, latest of all, as new as possible, the victorias.

the broad sweeping drive. This was a triumph of American engineering and, I had no doubt, an improvement on the informality of rocks and debris that had existed before. Yet I should liked to have seen it when the promenade had not yet been laid down with mechanical precision, in, perhaps, the early seventies. Then there were sea baths cut in the live rock at the end of the Paseo Isabel, at the Campos Eliseos, where the water was like a cooler liquid green air, and where, after storms, a foaming surf poured over the barriers. There were no motors then, but volantes and the modern quintrins[sic], with two horses, one outside the shafts, and a riding calesero in vermilion and gold lace; and, latest of all, as new as possible, the victorias.

Neither, then, was the Prado paved, but the trees were infinitely finer—five rows there were in fifty-seven—when the clamor of the city was, in great part, peals of bells. This was a familiar process with me, to leave the present for the past in a mood of irrational regret. But never for the heroic, the real past; the years I chose to imagine lay hardly behind the horizon; in Italy it had been the  Risorgimento, at farthest the villeggiatura of Antonio Longo or the viole d'amore of Cimarosa in churches. And now, drinking my champagne on the empty flagged terrace of the Miramar, facing, across the parade of automobiles, the blank curtain of the night, starred on the right by the lights of castellated forts, my mind vibrated with grace notes no longer heard outside the faint distilled sweetness of music boxes.

Risorgimento, at farthest the villeggiatura of Antonio Longo or the viole d'amore of Cimarosa in churches. And now, drinking my champagne on the empty flagged terrace of the Miramar, facing, across the parade of automobiles, the blank curtain of the night, starred on the right by the lights of castellated forts, my mind vibrated with grace notes no longer heard outside the faint distilled sweetness of music boxes.

As if in derision of this, a loud unexpected music rose from the bandstand in the Plaza, and I saw that a flood of people, seated or moving along the pavements and through the lanes of chairs, had gathered. Nothing, I thought, could have delighted me more; but my anticipation was soon smothered by the absurdity of the selections: they were not from Balfe nor Rossini, neither military nor the accented rhythm of Spain . . . the opening number was Parsifal, blown into the profound night with a convention of brassy emphasis.

[...]

p. 63 – 67

Joseph Hergesheimer. San Cristóbal de La Habana. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1920.