Crafting Shipwrecks in Havana: A Prelude

Margarita Zamora, University of Wisconsin

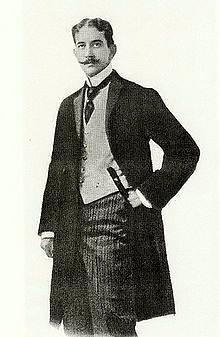

In 1908, the young Cuban writer, caricaturist, and amateur painter Jesús Castellanos, traveled to Paris. It is not difficult to imagine the details of a likely itinerary that would place him in the Louvre one autumn day in that same year. There, on the first floor in the Grande Gallerie which houses the largest paintings in the museum’s collection, he would not have missed the immense canvas hanging almost at floor level. The artist himself had requested it be placed down low so that the spectator could take full measure of the life-size depiction of the raft and its occupants, and perhaps imagine stepping into the tragic scene.

In 1908, the young Cuban writer, caricaturist, and amateur painter Jesús Castellanos, traveled to Paris. It is not difficult to imagine the details of a likely itinerary that would place him in the Louvre one autumn day in that same year. There, on the first floor in the Grande Gallerie which houses the largest paintings in the museum’s collection, he would not have missed the immense canvas hanging almost at floor level. The artist himself had requested it be placed down low so that the spectator could take full measure of the life-size depiction of the raft and its occupants, and perhaps imagine stepping into the tragic scene.

Castellanos would be standing at the foot of Théodore Géricault’s masterpiece, “Le radeau de la Méduse” (“Raft of the Medusa”). The painting represents a makeshift raft crowded with the survivors of a shipwreck, adrift in roiling seas as storm clouds close in. The raft fills most of the 4.91 x 7. 17 meters of canvas, but only a small part of its surface is visible because it is strewn with bodies upon bodies; some in the last stage of survival, some still alive enough to hope for rescue, while others, lifeless already, dangle limbs over the water. A man clings to a boy’s corpse to keep it from sliding into the deep. Next to them, a bust has lost its pelvis and lower extremities, to ravenous sharks perhaps. The chiaroscuro illumines tortured flesh, but it is difficult to make out most of the faces. Muscle and sinew are left to speak the horror and despair. A strong diagonal draws the spectator’s eyes to the right upper quadrant of the canvas, where two figures with backs turned to the viewer are waving pieces of cloth toward an object in the distance. In a plane just behind them, other survivors reach out in the same direction with arms outstretched toward the far horizon. Following their gaze, the spectator can barely make out the faint outline of what seems like a sail receding into the distant gash of light.

An occasional reviewer of the arts, Castellanos oddly left no record of a visit to the Louvre. Yet it seems inconceivable, that his sojourn in Paris in the autumn of 1908 would not have included a visit to one of the world’s most renowned art museums. Whether he sought out Géricault’s masterpiece or simply stumbled upon it, the startling canvas must have impressed the visitor from an island accustomed to disasters at sea. He may have learned then that “The Raft of the Medusa” was inspired by a true story of shipwreck; a story that must have impressed Castellanos as much the painting itself. Géricault’s massive oleo depicts the aftermath of the most publicized sea disaster of the nineteenth century: the wreck of the French frigate, “Méduse,” which ran aground on the Bank of Arguin in 1816, during a mission to reassert control of the French colony in Senegal. The incident became notorious in the press for the incompetence, irresponsibility, and inhumanity of the ship’s captain. Hugue Duroy de Chaumereys, a royalist loyal to the Bourbon monarchy of the Restoration appointed to the helm thanks to his political connections. When the ship ran aground because of Chaumerey’s unfamiliarity with the treacherous waters off the West African coast, 149 people were left to fend for themselves in a makeshift raft while the officials and their families rowed to safety. For two weeks they drifted in the ocean enduring thirst, hunger, rebellion, and cannibalism after the rope that secured the raft to the captain’s boat was severed. Only 15 of the original 149 survived the ordeal.

impressed the visitor from an island accustomed to disasters at sea. He may have learned then that “The Raft of the Medusa” was inspired by a true story of shipwreck; a story that must have impressed Castellanos as much the painting itself. Géricault’s massive oleo depicts the aftermath of the most publicized sea disaster of the nineteenth century: the wreck of the French frigate, “Méduse,” which ran aground on the Bank of Arguin in 1816, during a mission to reassert control of the French colony in Senegal. The incident became notorious in the press for the incompetence, irresponsibility, and inhumanity of the ship’s captain. Hugue Duroy de Chaumereys, a royalist loyal to the Bourbon monarchy of the Restoration appointed to the helm thanks to his political connections. When the ship ran aground because of Chaumerey’s unfamiliarity with the treacherous waters off the West African coast, 149 people were left to fend for themselves in a makeshift raft while the officials and their families rowed to safety. For two weeks they drifted in the ocean enduring thirst, hunger, rebellion, and cannibalism after the rope that secured the raft to the captain’s boat was severed. Only 15 of the original 149 survived the ordeal.

Among the survivors were the ship’s surgeon, Dr. Henri Savigny, and Alexandre Corréard, the expedition’s geographical engineer, collaborators on a testimonial account—Narrative of a Voyage to Senegal in 1816—that exposed the government’s  failure in its duties to its citizens. Defying the secrecy and censorship surrounding the disaster, Corréard and Savigny reworked the original account, adding illustrations and corroborating testimony with each new edition. A series of engravings by Géricault were included in the lavish third edition of the five that were published in as many years.(1) Géricault’s collaboration on the edition and his friendship with Corréard, who had been in and out of prison for the publication of a text deemed “seditious” by Bourbon officials, suggests that he sympathized with the liberal opposition. But it was the monumental canvas that immortalized the shipwreck Corréard and Savigny’s narrative had exposed as the height of governmental irresponsibility and incompetence, testifying to the painter’s larger ethical political concerns.

failure in its duties to its citizens. Defying the secrecy and censorship surrounding the disaster, Corréard and Savigny reworked the original account, adding illustrations and corroborating testimony with each new edition. A series of engravings by Géricault were included in the lavish third edition of the five that were published in as many years.(1) Géricault’s collaboration on the edition and his friendship with Corréard, who had been in and out of prison for the publication of a text deemed “seditious” by Bourbon officials, suggests that he sympathized with the liberal opposition. But it was the monumental canvas that immortalized the shipwreck Corréard and Savigny’s narrative had exposed as the height of governmental irresponsibility and incompetence, testifying to the painter’s larger ethical political concerns.

Géricault did extensive research for the “Raft of the Medusa” that included observations of cadavers in various stages of decomposition, the construction of a model of the raft, and interviews with the survivors. He then produced several studies. Thanks to one of those studies we know that the elusive object on the far horizon that captured the attention of the castaways was in fact the frigate “Argus” that would eventually rescue them. For the final version of the painting, however, Géricault decided to depict the raft and its occupants in the moment of greatest tension, suspended between waves of hope and despair, when salvation appeared at last in the distance only to vanish with the receding “Argus,” which missed the raft on its first pass.

and its occupants in the moment of greatest tension, suspended between waves of hope and despair, when salvation appeared at last in the distance only to vanish with the receding “Argus,” which missed the raft on its first pass.

An important aspect of Géricault’s masterpiece is the exquisitely nuanced way it straddles the boundary between the ethical and the political. Working the paradigm of shipwreck as abandonment inherited from his Romantic predecessors, Géricault added ethical political bite in two striking innovations: the depiction of the mixed social class and racial composition of the group of castaways and the ironic inversion that rendered the promise of rescue on the horizon as a false of hope.

Jesús Castellanos’s reading of Géricault’s masterpiece became Cuba’s first great short story, “La agonía de La Garza;” a narrative about a humble shipwreck off the Matanzas coast that testifies to the ethical and political failures of the island’s first post-colonial government. That story sparked the editor’s interest in the theme of shipwreck, an interest that ultimately led her to this special issue of La Habana Elegante. It is fitting, therefore, that “Naufragios/Shipwrecks” be dedicated to the memory of Castellanos, who taught later generations of Cuban writers and readers that it is not about the sea but the shipwreck.

Nota

1. Jonathan Miles, The Wreck of the Medusa: the Most Famous Sea Disaster of the Nineteenth Century, (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2007) is the most complete source on the history of the wreck and Correárd and Savigny’s account.