Collections, Nation and Melancholy at the World’s Fair: Re-reading Mexico in Paris 1889

Shelley E. Garrigan, North Carolina State University

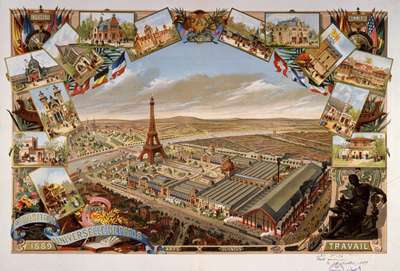

Held approximately every two to four years between the first large international exposition (at The Crystal Palace in England, 1851) and World War I, the late nineteenth-century world’s fair events helped construct a Western paradigm focused on modernity and progress. The most imposing, the most propagated, and the most influential international constructions of the late nineteenth-century were the world’s fair expositions, which as precursors to the age of globalization offered a medium not only for the creation of commercial relationships among competing nations, but also for the international transmission of information and culture. Indeed, as international mediums of transmission in which information and product consumption occurred in the same venue, the nineteenth-century world’s fairs can be construed as precursors to the internet. The Fair was a spectacular instrument of mass communication, a modeling medium that not only staged a series of self-conscious displays of nationhood but also mobilized the commercial relational matrix that was established in the nexus of expository mania.

Held approximately every two to four years between the first large international exposition (at The Crystal Palace in England, 1851) and World War I, the late nineteenth-century world’s fair events helped construct a Western paradigm focused on modernity and progress. The most imposing, the most propagated, and the most influential international constructions of the late nineteenth-century were the world’s fair expositions, which as precursors to the age of globalization offered a medium not only for the creation of commercial relationships among competing nations, but also for the international transmission of information and culture. Indeed, as international mediums of transmission in which information and product consumption occurred in the same venue, the nineteenth-century world’s fairs can be construed as precursors to the internet. The Fair was a spectacular instrument of mass communication, a modeling medium that not only staged a series of self-conscious displays of nationhood but also mobilized the commercial relational matrix that was established in the nexus of expository mania.

Mauricio Tenorio-Trillo’s exhaustive and groundbreaking study of Mexican participation in world’s fairs (with special emphasis on the Exposition Universelle de Paris in 1889) centers on the implicit tensions between image and thing, or form and essence, when he argues that the commissioners in charge of the Mexican exhibit for Paris in 1889 found themselves in the difficult position of representing a nation that did not yet exist. Indeed, the problem of fashioning an image of national selfness that can only be problematically or partially representative of reality is a central characteristic of nineteenth-century exposition culture as a whole, and not just an attribute of Mexico as a developing nation.

Arguments seeking to explain Mexico’s “unoriginal” aesthetic (prior to the post-revolutionary muralists), which can be found in Daniel Schávelzon’s La polémica del arte nacional en México (1850-1950) and Roger Bartra’s La jaula de la melancolía, have pointed diagnostically toward an inherent sense of Mexican national depression. But a closer glimpse at the circumstances under which the United States and European nations hosted world’s fairs suggests a frequent contrast between the semi-depressed or melancholic state of a nation in recovery and the sublime, compensatory events proposed by the Fair. In addition, recognizing that both European and Mexican fair displays played with practices of self-exoticism in order to attract potential viewers and investors helps collapse the presumed differences between Mexico and the developed world. These realities complicate the commonplace distinctions that privilege the nineteenth-century material self-representations of Europe and the United States over those of the developing world; indeed, trends in world’s fair collection building suggest the idea of melancholy as foundational to identity construction in all modern states.

I. Constructing an Image

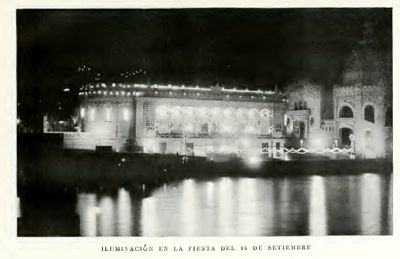

While the articulations of an emerging selfhood that characterize late nineteenth-century Mexico are in no way limited to the Fairs, these were considered to be of primary importance for the stimulation of national development during the Porfiriato and so had a significant impact on local industrial and aesthetic developments. Witness, for example, the following observations written by Sebastián de Mier in his official account of Mexico’s participation in the Paris fair of 1900:

observations written by Sebastián de Mier in his official account of Mexico’s participation in the Paris fair of 1900:

Very complex are the causes of the material progress observed in Mexico in recent years, revealed by the new enterprises created. . . . There is no denying that one of them is the attendance at the Expositions. After each one of these events, great steps forward for the nation have been achieved, thanks in large part to the publicity associated with them, to the things that have been learned there, and to the fervor and excitement that both constitute and result from the very essence of these tournaments among nations. (De Mier, 8)

World’s fairs were venues where individual nations could perform and to a certain extent reinvent themselves. However, exhibits were uncompromisingly subject to specific parameters, standards, and norms. Blueprints for fair pavilion projects, for example, were submitted to host countries for approval before construction. The spatial layout of the fairgrounds were meticulously determined and organized in such a way that sustained the rigid social and economic hierarchies that describe nineteenth-century Anglo-European hegemony. The hyperconsciousness that surrounded the processes of self-edification inspired by the world’s expos lead fair commissioners and representatives from all branches of aesthetics (the plastic arts, for example) to study their competitors’ work while still figuring out their own modes and materials of display.

In the archive for the Exposition Universelle de Paris of 1889, for example, there is a folder containing a drawing and detailed description of the Argentine pavilion intended for the same fair, indicating the competitive edge against which such sublime articulations of nation were conceived. Along the same lines but on a broader scale, the published Guía del archivo de la Antigua Academia de San Carlos (with memos dating from 1867-1907) contains multiple mentions of the travel stipends used to send artists to study the local practices of European artists at workshops in Rome and Paris, while simultaneously the parameters for a specifically national expression were being sought and explored:

- Instructions to C. Emiliano Valadez about the work to which he should dedicate himself during his stay in Europe.

- To study and practice . . . all that relates to the fabrication of dyes, varnishes and other components used for engravings, [which is] deficient nowadays amongst us.

- To study what is new in systems for cooling down steel plates and molds and die and however much you find that is new and good. (Guía del Archivo, 182)

Due to the hyperconscious and competitive atmosphere — indeed, the market mentality that underlay so much of  aesthetic practice during this late nineteenth-century time juncture — contemporary writers on the Mexican aesthetics of the nineteenth century have expressed retrospective concern over the construction of a subjectivity that, precisely because of its hyperconsciousness, ultimately compromised its own authenticity:

aesthetic practice during this late nineteenth-century time juncture — contemporary writers on the Mexican aesthetics of the nineteenth century have expressed retrospective concern over the construction of a subjectivity that, precisely because of its hyperconsciousness, ultimately compromised its own authenticity:

The point that has seemed most important to us from the beginning is the attempt to construct a type of art or architecture of national characteristics, but as the result of an a priori creation; that is, a social group proposes to create a national art, and from there give it form, without keeping in mind that this art could only be the result of a complex historical process. (Schávelzon, 11)

Along the same lines, early twentieth-century cultural critic Martín Luis Guzmán expresses a similar criticism of Mexican nationalism during the chaos of the revolution, only grounding his observations more in the political realm (Vásquez de Knauth, 129). According to writers like Guzmán, Mexico’s error was reversing the organic progression of full self-realization by forging the parameters of a fully edified patria (or an “ideal” of patria as represented in art and architecture) before “deserving it.” In other words, the self-conscious products of a rushed process of self-edification cannot replace the organic, unconscious workings of history. It is the “complex historical process,” or, in the words of Guzmán, the spontaneous “feeling of the homeland like a generous impulse” that produces the fully realized and autonomous national polity — not the competitive drive of constant comparison.

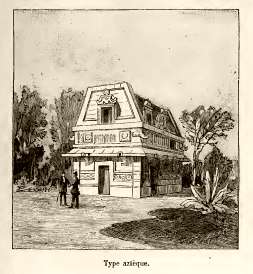

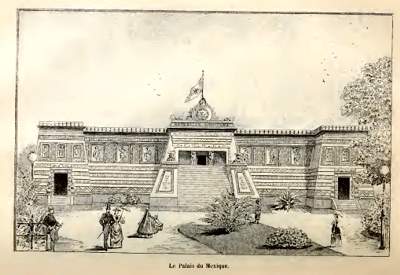

One example of market-driven cultural production — as opposed to organic historical process — is the Palacio azteca itself, which was ultimately considered by future architects to be a failed experiment in cultural production due to its unoriginality (as its blueprints were influenced in part by the notes of foreign explorers and writers), its uselessness, and its failure to become a permanent fixture within the growing repertoire of public places back in the Federal District. Witness the following criticism written during the decade that followed 1889:

failure to become a permanent fixture within the growing repertoire of public places back in the Federal District. Witness the following criticism written during the decade that followed 1889:

We see, then, that the building is not useful, since it has remained disassembled for ten years [and] who knows where . . . without serving any purpose whatsoever; it doesn’t express truth, as has been proven, nor beauty, since it doesn’t correspond to our current tastes, nor to the principles of absolute beauty. Other writers were more frank and hard, calling the building the great water tank. (Schávelzon 152, translation mine)

To further its multiplicity of meanings, the Palacio was conceptualized and designed as a structure that could be disassembled at the close of the fair and reassembled in Mexico as an archaeological museum, a prospect that was never realized (Ramírez, 210).

A more detailed analysis of Mexico’s depressive, market-driven cultural production, found in the writings of journalist and cultural critic Roger Bartra, helps to integrate these criticisms of the Palacio azteca into a broader context of cultural reflection. In “El luto primordial,” Bartra reflects on the rhetorical appropriation of melancholy as the definitive Mexican character. Distinguishable in literary, medical and analytical writings as far back as the turn of the nineteenth-century, he writes, such “melancholy” need not be uncritically attributed to the social and political misfortunes that characterize the prototypically “backward” ex-colony, as might be assumed from writings such as Paz’ Postdata and García Márquez’ Cien años de Soledad (58). Basing his observations on post-revolutionary novels, the author focuses on the “myth of the heroic peasant” and the inevitable longing for a better life that converts his existence into a ceremony of mourning, a “body sacrificed on the altar of modernity and progress” (47). Rather than as an originating condition developing organically from a detained economic and political instability, Bartra reads Mexican melancholy in light of the overall hyperconscious process of construction of an autonomous identity in which the Mexican national polity has appropriated and internalized the historical “ideas-tipos” (idea-types) imposed on them by centuries of Eurocentric discourse (51).

Far from advocating an essentialist and reductive interpretation of mexicanidad with this particular reading, melancholy should be understood in this context as a foundational story — one that is put to strategic use in the various institutional articulations of autonomy that accompany the fin de siglo juncture and the height of the porfiriato. From the literary articulations of Mexican romantic poets such as Ignacio Rodríguez Galván and Salvador Díaz Mirón to the cult to Cuauhtémoc and other tragic heroes (such as Miguel Hidalgo) immortalized in the monuments that adorn the Paseo de la Reforma, there is a link between the institutionalized usage and popularization of sentiment and the notion of political and cultural unity that congeal in the late nineteenth century:

In this way, the definition of the national character is not a mere problem of descriptive psychology: it is a political necessity of the first order, […] contributing to the establishment of the bases of a national unity to which the monolithic sovereignty of the Mexican state then corresponds (Bartra, 226) (translation mine).

This attribute of Mexicanness that Bartra identifies, however, is not exclusive to Mexico, or even Latin America in general. If anything, continues the author, this melancholic disposition is precisely what brings Mexico to the fore of modern  Occidental culture. Citing Lyotard, he routes the notion of a fundamental cultural nostalgia through the disposition that is “peculiar to the modern aesthetic, which finds in the cult to the sublime — the unattainable — a normative unifying consensus” (58). In other words, melancholy does not simply point backward to loss, but it also rather contradictorily exercises an edifying function in which stories and different embodiments of loneliness and melancholy are used as the foundations for a cohesive political national story to which everyone with that shared history suddenly belongs.

Occidental culture. Citing Lyotard, he routes the notion of a fundamental cultural nostalgia through the disposition that is “peculiar to the modern aesthetic, which finds in the cult to the sublime — the unattainable — a normative unifying consensus” (58). In other words, melancholy does not simply point backward to loss, but it also rather contradictorily exercises an edifying function in which stories and different embodiments of loneliness and melancholy are used as the foundations for a cohesive political national story to which everyone with that shared history suddenly belongs.

Before elaborating further on the case of Mexico, it would be useful to place Bartra’s use of melancholy in dialogue with Freud’s 1915 essay “Mourning and Melancholia.” According to Freud, what distinguishes the melancholic is the inability to properly distinguish between the self and the lost other. The melancholic disposition refuses to recognize a loss that has occurred, and so responds by incorporating some trace of the lost object into its own identity. In contrast with mourning, in which the location of the lost object is external to the self, the melancholic internalizes the lost love-object, converting it into a fundamental component of the ego. The characteristic hatred that would normally accompany the feelings of love for the external love-object is then internalized, causing the ego to turn upon itself. The melancholic subject thus convinces itself of its worthlessness, leading to a state of excessive self-torment.

Bartra, however, in positing the melancholic response to the loss of an ideal as constitutive rather then excessive, and in reading the edifying idea of loss as perhaps an essential cultural component of the modern polity, points to Judith Butler’s political reading of Freud in The Psychic Life of Power. Not only is melancholia’s contraction of the “social” (that which is outside the self) into the self the originating condition for the emergence of the ego, reads Butler, but it is through this occurrence that the Law disappears as an outside object and becomes mistaken for a component of the melancholic’s (i.e. citizen’s) own conscience. With both Butler and Bartra, then, the melancholic disposition is unleashed from the realm of individual idiosyncrasy and used to decipher social tendencies. In Mexico, it is the coming-of-age conflict in the onset of modernity that pushes the governmental elite to fabricate the symbols of a national identity within the parameters of the “universal” hegemonic social and scientific discourses of that era. Bartra comments on the historical incorporation of idealized “others” within the Creole articulations of identity, claiming that the internalization of imposed “stereotypes” and “powerful ideas” inevitably influence the behavior of the inhabitants of a nation (51).

There are two responses to this melancholic internalization of otherness that are historically discernible in Mexican culture, writes Bartra. One is the “tragedy of the fall” and martyrdom. The other is the “ecstatic” response derived from Aristotle and the Hippocratic concept of the four humors, “one of which — black bile — had an increasing importance in the definition not only of sickness (melancholy) but also a peculiar state of mind…” (55). This would be the state of genius discernible in the philosopher, the artist, or the politician whose contact with the obscure otherness of self and society generates an ecstatic overcoming — “an ecstasy that permits the soul to distance itself from the body, driven by a profound nostalgia for the same earthliness that it abandons.” This is the ecstasy of the visionary whose suffering inspires a resigned profundity of thought that has been celebrated in art, literature and politics throughout the ages (57). For Bartra, the heroic dimension to melancholy is undeniable in the political articulations that fashion a given nation’s self-justification of autonomy and agency.

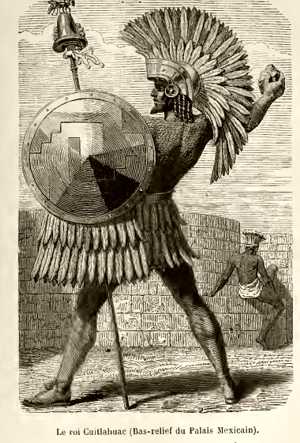

For a concrete example of the necessary relationship between melancholy and nation as suggested by Bartra, one need not look further than the pavilion exterior of the Palacio azteca itself. As Tenorio-Trillo provides an exhaustive description of the pavilion exterior in his World Fair study (96 –112), I will focus on one significant detail here: the statue and accompanying textual supplement to the representation of the last Aztec king Cuauhtémoc. Indeed, the transition of sanctity from deity to polity is epitomized in the sculpted representation of Cuauhtémoc, the last and most tragic of the nation’s indigenous leaders, whose dead and tortured body, reads the published Explication of the same building, “divided into two bloody pieces”was “the baptism of America” (Ramírez, 231).

Through Cuauhtémoc’s demise, the epic of death and loss founds the new political entity. The transcendent melancholic perspective as elaborated by Bartra and suggested in the Explicación cited aboveis one that penetrates the tragic immediacy of ruin and perceives, in the torn fragments of the hero, the newborn patria. While the figure of the Aztec hero on the pavilion exterior is solid in its sculpted form, its textual exegesis, published in Explication de l’Edifice Mexicain (Explanation of the Mexican Building) in a trilingual edition written by historian Antonio Peñafiel and distributed to fair visitors, allocates signification not to the depicted whole but rather to the divided pieces of the hero’s body. In the play between its fragmentation and reassembly in the exegetical synthesis that is generated between sculpture and text, the body of Cuauhtémoc becomes emblem of a national story. Not unlike the writers who created the tragic heroes explored in Benjamin’s study of the Trauerspiel or German tragic drama, the authors of the written Explicación use Cuauhtémoc’s martyrdom as a founding national story, thus imposing the physical trials of a single heroic individual onto the breadth of history itself (Benjamin, 91).

of ruin and perceives, in the torn fragments of the hero, the newborn patria. While the figure of the Aztec hero on the pavilion exterior is solid in its sculpted form, its textual exegesis, published in Explication de l’Edifice Mexicain (Explanation of the Mexican Building) in a trilingual edition written by historian Antonio Peñafiel and distributed to fair visitors, allocates signification not to the depicted whole but rather to the divided pieces of the hero’s body. In the play between its fragmentation and reassembly in the exegetical synthesis that is generated between sculpture and text, the body of Cuauhtémoc becomes emblem of a national story. Not unlike the writers who created the tragic heroes explored in Benjamin’s study of the Trauerspiel or German tragic drama, the authors of the written Explicación use Cuauhtémoc’s martyrdom as a founding national story, thus imposing the physical trials of a single heroic individual onto the breadth of history itself (Benjamin, 91).

Bartra’s analysis provides a bridge to connect the idea of a fundamental deficit — a constitutional gap or sense of incompletion that describes, according to this writer, not only those nations with a colonial past —to the huge endeavors of self-representation that mark the nineteenth century. One argument against Mexico’s allegedly failed experiment with modernity is that it is precisely this lack of a seamless political and representational topography that characterizes any modern nation. Critical reflections on European or U.S. fairs reveal that one of the fundamental functions of most nineteenth and early twentieth-century fairs was to construct a type of band-aid to cover an otherwise jagged seam of destabilizing national catastrophes such as war, economic crisis, and political unrest. For example, in a groundbreaking study on nineteenth-century fairs in the United States, Robert Rydell contrasts the stark historical reality of the 1876 Civil War Reconstruction period with the utopias projected in the U.S. fairs of that era.

In his history of great exhibitions, Paul Greenhalgh, in turn, draws attention to the gradual shift in priority, detectable from 1867 on in Europe, from provoking the admiration of the middle and upper classes to educating the impressions of the youth and the lower classes, in direct response to their potentially destabilizing emergence as “socio-political forces” (22). Still along the same lines, Mauricio Tenorio-Trillo points out that the 1889 Paris Centennial fair “helped France persuade itself of its greatness” while still recovering from the loss of Alsace and Lorraine to Prussia (22). In other words, all of the identities that were displayed at these great theaters of progress were elaborate performances in which fears of destabilization, compensation and loss helped shape the very narratives of progress that were generated to conceal them. This sense of an inherent and irrecuperable depletion is precisely the mobilizing force that empowered the celebratory inventions of nationalism that were erected. At the same time, the sense of precarious identity and inherent instability linked to commercial value somehow sustained rather than depleted the sublime national myths that were simultaneously being constructed, written, and disseminated.

Like the world’s fair architectural pieces in which myth-sustaining structures were assembled and dissembled in a matter of months, the collections displayed at these fairs also embodied a fundamental ambivalence between presence and dissolution. For example, the collector as represented in late nineteenth-century fiction, such as José Fernández in De sobremesa or Des Esseintes in A rebours, empties his collected pieces of their “otherness” in order to transform them into a extension of self and fill them with the fictions of his subjectivity. The official collected piece of the public institution, in turn, undergoes a similar emptying of its historical and circumstantial use-function, only the “filling” through which it becomes imbued with social meaning is discursive in nature and related to officially sanctioned disciplines rather than subjective fantasy. In both cases, something is lost in the complicated processes of assembly that precede the polished and finished display – both the collection and the depressed modern nation that it represents approach a disposition of mourning.

Despite ingesting the European visual vocabulary of modernity, Mexico nevertheless ventured to produce its own story. Together with the overwhelming anthropological scope of the fairs, there was an awareness that otherness sells, and the strategic practice of self-exoticism with an explicit marketing purpose was not unknown even among the European nations. For example, there appears to be an analogy between the marketing strategies of regional fairs in countries with powerful capital cities, as depicted in Shanny Peer’s reading of the use of folklore during the French fair of 1937, where marginal rural economies were boosted by promotion of “the authentic local,” and the strategic position taken by Latin American nations relative to the economic hegemony. In other words, the strategic economic use of the status of “otherness” was every bit as powerful, as well as much more overtly maneuverable, as the protagonist’s role within the biased anthropological discourses that had for centuries justified European claims of supremacy.

II. The Persuasiveness of Collections

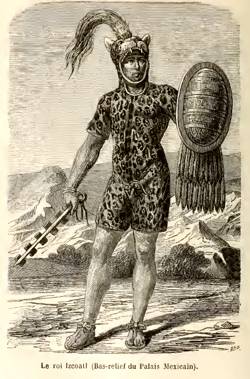

The Palacio azteca provides a blatant example of Mexico’s strategic use of otherness for the purpose of attracting a foreign viewing public. On the outside of the pavilion, which was modeled after an Aztec temple or teocalli, the rise and fall of the Aztec legacy was emblematized through a juxtaposition of abstract symbols and anthropomorphized representations of  selected gods and fallen kings from the Aztec pantheon. According to Tenorio-Trillo, the building synthesized an array of quotes and images taken from a variety of sources, spanning from Mexican anthropologist Alfredo Chavero’s Volume 1 of the newly consolidated first exhaustive account of Mexican history (México a través de los siglos) to European documentations of travel and archaeological descriptions such as those composed by Lord Kingsborough, Guillaume Dupaix, and Désiré Charnay. Art historian Fausto Ramírez also points out that the gods chosen to represent antiquity conformed to modern values: Centéotl, the protector of agriculture; Xochiquetzal, the deity of the arts; Camaxtli, god of the hunt; and Yacatecuhtli, the god of commerce (225, translation mine). Still, the point of the pavilion exterior was to emblematize the rise and fall of the Aztec empire through a strategic selection of pre-Columbian representations.

selected gods and fallen kings from the Aztec pantheon. According to Tenorio-Trillo, the building synthesized an array of quotes and images taken from a variety of sources, spanning from Mexican anthropologist Alfredo Chavero’s Volume 1 of the newly consolidated first exhaustive account of Mexican history (México a través de los siglos) to European documentations of travel and archaeological descriptions such as those composed by Lord Kingsborough, Guillaume Dupaix, and Désiré Charnay. Art historian Fausto Ramírez also points out that the gods chosen to represent antiquity conformed to modern values: Centéotl, the protector of agriculture; Xochiquetzal, the deity of the arts; Camaxtli, god of the hunt; and Yacatecuhtli, the god of commerce (225, translation mine). Still, the point of the pavilion exterior was to emblematize the rise and fall of the Aztec empire through a strategic selection of pre-Columbian representations.

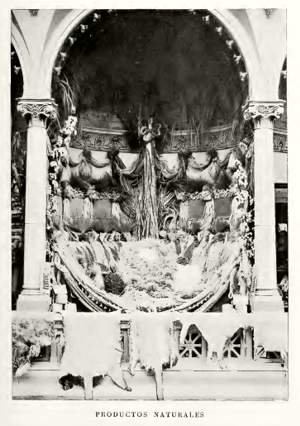

In contrast to the eclectic resurrection of the Aztec past displayed on the exterior of the Palacio azteca, the building’s interior offered a purely modern display of collections — meticulously divided into the exhibit categories established by the host nation’s fair commission — which emphasized raw materials, geography, education, production, and science. In accordance with this totalizing image of raw materials, abundance, and ripeness for commercial exploitation, fair commission member Sebastián de Mier’s retrospective observations on the 1889 fair confirm that affirmations of quantity and availability of raw materials took precedence over any pretense of selection or quality of products made from those materials:

The criterion that those favorable conditions imposed on our government in 1889 was to send everything possible to Paris, paying more attention to quantity than quality. The idea was to put on the most complete and general exhibit possible, and thus show Europe all the natural wealth of the country, all the developed products, and all the products of its manufacturing industries, showing off both provident nature and the intelligence and skill of the workers, so that the Exposition could demonstrate our productive potential (22).

Not to worry that the products made from the raw materials might have been of secondary quality, continues de Mier. For “countries such as ours, endowed with natural richness and lacking in capital to exploit them,” the principal aim was not so much to market its own industries as to attract foreign capital for the foundation of superior ones, “in order to produce better and more cheaply, with secured profits” (22).

This transition from the outside to the inside of the Aztec Palace — from the representation of antiquity to that of modernity — requires further elaboration. First, there is the national re-appropriation of the indigenous gods represented on the pavilion exterior and their re-assignation of meaning: where they had once represented European scientific hegemony and the exoticism of Mexican antiquity, they now stood for the status of Mexican national production and industry. This shift in meaning, an ability inherent to collected objects, is precisely what enables the theoretically opposed transcendent and commercial realms to intersect. The juxtaposition of old cultural referents on the exterior with new categorizations and ideologies inside reveals the hidden underside of collecting: in the effort to preserve what has been deemed sacred (history), the addition of new contexts and layers of signification (the criteria for collection organization, for example — which will inevitably be more “modern” than the objects collected) enables the nation to both ground its new status in history and imbue historical referents with a sense of currency and relevance. In addition, it is the ability of the collected object to shift in meaning (or embody more than one meaning at the same time) that allows Mexico to use the same objects to represent political consolidation and modern commercialization.

and the exoticism of Mexican antiquity, they now stood for the status of Mexican national production and industry. This shift in meaning, an ability inherent to collected objects, is precisely what enables the theoretically opposed transcendent and commercial realms to intersect. The juxtaposition of old cultural referents on the exterior with new categorizations and ideologies inside reveals the hidden underside of collecting: in the effort to preserve what has been deemed sacred (history), the addition of new contexts and layers of signification (the criteria for collection organization, for example — which will inevitably be more “modern” than the objects collected) enables the nation to both ground its new status in history and imbue historical referents with a sense of currency and relevance. In addition, it is the ability of the collected object to shift in meaning (or embody more than one meaning at the same time) that allows Mexico to use the same objects to represent political consolidation and modern commercialization.

With respect to the pavilion exterior, publicist José F.Godoy reads this particular architectural endeavor as a gesture of nationalism: “If the Commission has fulfilled its commitment, if it has managed to restore in this project the most important relics of ancient Mexican art, it will have performed an act of true patriotism” (68). Indeed, there are within the fair archives several references to the transcendent nationalism represented by this architectural piece with which engineer Luis Salazar proposed to found a new and specifically national architectural style.  Ironically, however, the pavilion’s exterior more closely mimicked the logic of the market than that of the museum. In other words, by appropriating European renditions of Mexican antiquity, juxtaposing disparate architectural styles, and standing as a temporary structure on the Parisian fair grounds, the exterior of the Palacio azteca embodies the transience, the substitutability, and the instability of commercial value.

Ironically, however, the pavilion’s exterior more closely mimicked the logic of the market than that of the museum. In other words, by appropriating European renditions of Mexican antiquity, juxtaposing disparate architectural styles, and standing as a temporary structure on the Parisian fair grounds, the exterior of the Palacio azteca embodies the transience, the substitutability, and the instability of commercial value.

Equally contradictorily, the interior of the pavilion, composed largely of manufactured goods and perishable raw materials, appropriated the aura not of a marketplace, but rather that of a museum exhibit. In an overwhelming attempt to override the bric-a-brac assembly referred to earlier by Sebastián de Mier with a disciplined and universal legibility, the catalogued exhibit of the interior followed a model of standardization — predetermined and distributed by Paris officials — that divided the objects into groups, subdivided them into classes, and then further subdivided them into the contributions of individual states. The individuality of the items, upon which such attention is placed on the building façade, is inside subsumed under the guise of the generic “piece” through the assignment of numbers to each object and their organization into lists. In assigning a number to each object, the viewer’s attention is deviated from thing to abstraction — producing what Baudrillard would call the “serial” perspective —which sublimates otherwise unrelated and de-contextualized objects into members of a category:

Group II: Education and Teaching—Material and Procedures

Class 8: Organization, Methods and Instruction Material

State of Aguascalientes.

469. –89a. The State of Aguascalientes, by González, 1 vol.

470. 89b. Elements of Chronology, by C. López, 1 vol.

471. 89c. Ethnological Essay of the State, 1 vol.

472. 89d. Code of procedure of the State, 1 vol.

473. 89e. Eulogy of Doctor J. Calero, 9 notebooks. (Catalogue, 25)

Furthermore, the meticulous categorization and precise division of produce and material productions into geographically and chronologically organized charts and graphs suggests a stability of meaning that more closely mimics the permanent museum exhibits of the era, rather than the whims of commercial value. The materials displayed in the pavilion’s interior were used to both represent something inherent or essential about the Mexican nation and point fairgoers toward projections around a future state of “completion” (understood to be a competitive level of national modern development). In this way, this particular world’s fair exhibit quite literally exemplifies the ways that the collector’s logic can be used to explain Mexico’s simultaneous edification of a national patrimony and its flirtations with commercial enterprise.

III. Competitive Spaces

Despite the intricacy of detail that would allow for exclusive concentration on only the fair pavilion structure, it is essential to consider its placement both within the fairground plans as a whole and with respect to neighboring national pavilions. Indeed, the space allotted to the Mexican fair commission is revealed in fair correspondence as just as important as the overall edification of the national exhibit itself. During the conceptual phase of the Exposition Universelle prior to its opening, certain fair commissioners representing Latin American nations became concerned with the space allotted to the Latin American exhibits. In a written report to the Secretaría of the Mexican delegation for the 1889 Paris fair, chief commissioner Manuel Díaz Mimiaga writes of a consensual discontent among the invited Latin American nations with respect to the territory to which they were assigned:

certain fair commissioners representing Latin American nations became concerned with the space allotted to the Latin American exhibits. In a written report to the Secretaría of the Mexican delegation for the 1889 Paris fair, chief commissioner Manuel Díaz Mimiaga writes of a consensual discontent among the invited Latin American nations with respect to the territory to which they were assigned:

Sr. Cristanto Medina had the good will to come to my house to tell me that he and some other General Commissioners from diverse Hispanic American countries, finding the ground around the Avenue de Suffren to be too narrow to construct their respective pavilions, have agreed to declare to the directors Berger and Alphand that the place is not acceptable, and that they desire to be given the necessary land from the parts designated for gardens in front of the Palace of Liberal Arts and next to the Eiffel Tower. (Mexico, Exposition, Box 1, Exp. 3.)

Besides the narrow land, continues Díaz-Mimiaga, the reason for this petition for a new space allotment has to do with augmenting the possibilities of “interest” and “success” of the Latin American exhibits by strategically distancing them from the European and U.S. pavilions and thus reducing their possibilities of an unfavorable comparison. There is an irony to the politics of space and presence witnessed here: one argues for representative autonomy when the ultimate object is social membership.

The nature of this agreement — to ensure that the designated territory for the Latin American expositions would constitute a space “of interest” within the international parade of pavilions — implies neither an undifferentiated alliance nor a  composed resignation on the part of the Latin American nations to form an unproblematic, seamless equivalency with respect to one another at the fair. Not only was the actual physical territory a point of contention for the Latin American nations, but also the abstract or conceptual space as initially defined and administered by the French hosts threatened to neutralize any possibility of individual agency for these nations. In his “confidential letter about the next International Exposition of Paris” (1889) to the Mexican fair committee, Crisanto Medina, the member of the Legation of Guatemala cited above, expressed great concern over the question of ensuring the creation of individual syndicates for each participating Latin American nation. Referring back to the one Spanish American Syndicate that had been created for the 1878 exposition, also hosted in France, Medina writes:

composed resignation on the part of the Latin American nations to form an unproblematic, seamless equivalency with respect to one another at the fair. Not only was the actual physical territory a point of contention for the Latin American nations, but also the abstract or conceptual space as initially defined and administered by the French hosts threatened to neutralize any possibility of individual agency for these nations. In his “confidential letter about the next International Exposition of Paris” (1889) to the Mexican fair committee, Crisanto Medina, the member of the Legation of Guatemala cited above, expressed great concern over the question of ensuring the creation of individual syndicates for each participating Latin American nation. Referring back to the one Spanish American Syndicate that had been created for the 1878 exposition, also hosted in France, Medina writes:

You will remember that back then the French imposed on us the Hispanic American consortium, and that the syndicate, which to a certain point took away our independence and ability to act, produced results that left much to be desired. Since then I have been opposed to a syndicate of that nature because of the problems that we faced then and that I had foreseen. I think the French administration not only lacks the right to make such a request, but also that it would breach the rules of courtesy and politics to demand as a condition for participating in the encounter that their Hispanic-American guests form only one body. (Mexico, “Exposition,” Box 11, Exp.1)

This same preoccupation with individual space allotments and autonomous national representations is echoed in the Mexican fair commission’s ultimate decline to participate, upon the invitation of a Monsieur Millas, in the creation of a “Public Industrial and Commercial Museum, formed especially with natural products from Latin America” (Exposition, vol 11, exp 12, p. 9). Such initiatives, writes Mexican diplomat and chief fair commissioner Manuel Díaz Mimiaga, had already been taken in the Havre, Liverpool, Amberes and Hamburg, with few benefits for Mexico due to the bias of the managers, who gave unfair preference to the producing countries that most interested them individually without paying proper attention to the rest of the exhibiting nations. For this reason, continues the fair commissioner, it “doesn’t behoove Mexico to confuse its products with those of other countries nor to initiate competition in such limited terrain” (10). Proposed as an alternative was the idea of setting up a series of “merchant museums” (Museos Mercantiles) within the Mexican consulates of key cities within various countries considered to be prime targets for initiating or increasing the exportation of Mexican produce: Germany, Belgium, Spain, the United States, France, Great Britain, Italy, Portugal, and Switzerland (10).

the exhibiting nations. For this reason, continues the fair commissioner, it “doesn’t behoove Mexico to confuse its products with those of other countries nor to initiate competition in such limited terrain” (10). Proposed as an alternative was the idea of setting up a series of “merchant museums” (Museos Mercantiles) within the Mexican consulates of key cities within various countries considered to be prime targets for initiating or increasing the exportation of Mexican produce: Germany, Belgium, Spain, the United States, France, Great Britain, Italy, Portugal, and Switzerland (10).

Based on these observations, it seems that autonomous representation at the fair was considered key not only for increasing the interest and attraction to the exhibits offered by individual participating Latin American nations, but also for the creation of a spirit of fair competition among those nations of similar rank. In this spirit, Mexico acquires a competitor and point of comparison with Argentina, as confirms Díaz Mimiaga:

It is generally believed, and with good reason, that our country along with Argentina would be the two that will attract the most attention because of the importance, variety, richness, and interest of their natural and industrial products. (Mexico, Exposition, Box.1, Exp.3)

As objects of one another’s gaze in the spirit of interested competition, Latin American nations justify their respective cultural autonomy to the international audience by demanding the proper space concessions. In this gesture, individual nations (rather than ex-colonies) assume their respective positions within the scope of the imagined space of the international trade circuits.

As the revolutionary abilities of science and technology to access or produce reality reproduced themselves tangibly in the marketplace, representation itself undergoes a shift from medium to subject in nineteenth-century Mexico. From this perspective, it is not so much the exhibit or the series of products in question that calls for attention, but rather the spatial, categorical, and abstract implications of  self-representation itself as exercised from within a set of externally and internationally-determined standards. The modes, places, spaces and contexts of display occupied center stage in the debates surrounding the exhibition culture of the late nineteenth-century era, in such a way that implies representation itself as the subject of the Mexican construction of modernization. While the same may be said indeed with respective to the hosting nations of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century world’s fairs, particular to the case of Mexico was the need to reconcile the colonial past and melancholic symptoms of an underdeveloped nation with the hyper-celebratory landmarks constructed for these events. If the subject of national and international scrutiny was indeed the question of representation itself, then the object, in turn, or the language or medium through which the new techniques of representation gathered force and achieved communicability, was the nation. This spectacular form of displacement—the exhibit as subject rather than medium-- posits the collection not merely as a set of things organized around a determined logic, but as a generator of both transcendent and practical, consumable meanings for the Mexico of the Porfirian regime.

self-representation itself as exercised from within a set of externally and internationally-determined standards. The modes, places, spaces and contexts of display occupied center stage in the debates surrounding the exhibition culture of the late nineteenth-century era, in such a way that implies representation itself as the subject of the Mexican construction of modernization. While the same may be said indeed with respective to the hosting nations of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century world’s fairs, particular to the case of Mexico was the need to reconcile the colonial past and melancholic symptoms of an underdeveloped nation with the hyper-celebratory landmarks constructed for these events. If the subject of national and international scrutiny was indeed the question of representation itself, then the object, in turn, or the language or medium through which the new techniques of representation gathered force and achieved communicability, was the nation. This spectacular form of displacement—the exhibit as subject rather than medium-- posits the collection not merely as a set of things organized around a determined logic, but as a generator of both transcendent and practical, consumable meanings for the Mexico of the Porfirian regime.

Works Cited

Aguirre, Robert. Informal Empire: Mexico and Central America in Victorian Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005.

Bal, Mieke. “Telling Objects: A Narrative Perspective on Collecting” in The Cultures of Collecting. Ed. John Elsner and Roger Cardinal. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Bartra, Roger. La jaula de la melancolía: identidad y metamorphosis del mexicano. México, D.F: Editorial Grijalbo, 1987.

Báez Macías, Eduardo, ed. Guía del archivo de la Antigua Academia de San Carlos 1867–1907. 3 vols. Mexico: UNAM, 1993.

Benjamin, Walter. The Origin of German Tragic Drama. London: NLB, 1977.

Butler, Judith. The Psychic Life of Power: Theories in Subjection. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1997.

Castillo de González, Aurelia. Un paseo por Europa cartas de Francia (Exposicion de 1889) de Italia y de Suiza. Habana: La Propaganda literaria, 1891.

De Mier, Sebastian B. México en la Exposición Universal Internacional de Paris —1900. Mexico City: Secretaria de Fomento, 1901.

Freud, Sigmund. Trauer und Melancholie: 1917. [S.l.]: Merck, Sharp & Dohme, 1972.

Godoy, José Francisco. México en París: reseña de la participación de la República mexicana en La Exposición de París en 1889. Mexico, D.F: Tipografía de Alfonso E. López, 1890.

Huysmans, J.-K., Margaret Mauldon, and Nicholas White. Against Nature. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Mexico. Exposition Universelle Internacionale de París 1889. Catalogue officielle de l’Exposition de la République Mexicaine. Paris: Générale Lahure, 1889.

--------. Exposiciones Internacionales. Archivo General de la Nación. Ramo Fomento. 1889.

Peer, Shanny. France on Display. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1998.

Peñafiel, Antonio. Explication de l’edifice Mexicain a l’Exposition Internationale de París en 1889. Barcelona: d’Espase et Compagnie, 1889.

Ramírez, Fausto. “Dioses, heroes y reyes mexicanos en París, 1889” en Historia, leyendas y mitos de México: su expresión en el arte (XI Coloquio Internacional de Historia del Arte). Mexico, D.F: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1988.

Rydell, Robert. All the World’s a Fair: Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876–1916. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984.

Schávelzon, Daniel, ed. La polémica del arte nacional en México, 1850-1910. Mexico, D.F: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1988.

Silva, José Asunción. De sobremesa. Madrid: Hiperión, 1996.

Stewart, Susan. On Longing. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1993.

Tenorio-Trillo, Mauricio. Mexico at the World's Fairs: Crafting a Modern Nation.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

Vásquez de Knauth, Josefina. Nacionalismo y educación en México. Mexico, D.F.: Centro de Estudios Históricos, 1970.